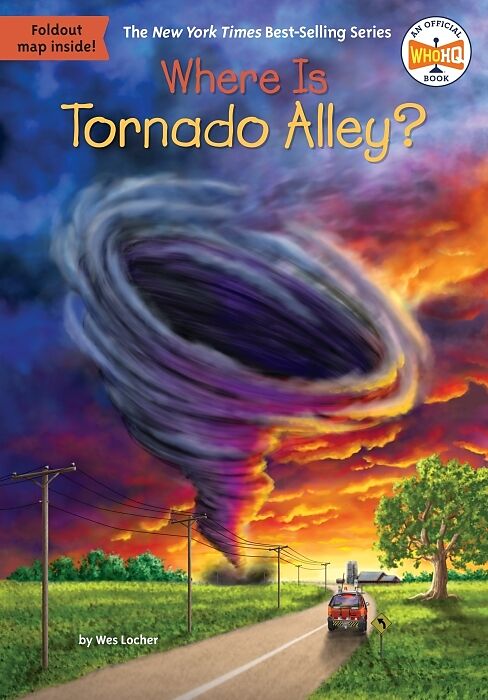

Where Is Tornado Alley?

Beschreibung

Learn about Tornado Alley, the area in the United States where tornadoes are most frequently formed and often cause the most damage. Robert Miller and Ernest Fawbush coined the term "Tornado Alley" after studying the pattern of tornadoes that occurred around T...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 11.40

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Learn about Tornado Alley, the area in the United States where tornadoes are most frequently formed and often cause the most damage.

Robert Miller and Ernest Fawbush coined the term "Tornado Alley" after studying the pattern of tornadoes that occurred around Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma. They determined that the highest number of tornadoes in the United States took place across states such as Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska. In this exciting new book, readers will learn about the history of Tornado Alley, other weather phenomena in the area, and what you can do when there is a tornado headed your way. The book also reveals how tornadoes are formed, how storm chasers do their work, and how they help researchers predict new tornado patterns.

Autorentext

Wes Locher; illustrated by Dede Putra

Klappentext

Issued with a detachable color map of the United States and its historical Tornado Alley areas, with photos on the map's reverse.

Leseprobe

Where Is Tornado Alley?

Captain Robert Miller was the meteorologist (an expert on weather forecasting) on duty the evening of March 20, 1948, at Tinker Air Force Base in central Oklahoma. While he had alerted the base of approaching wind gusts of thirty-five miles per hour, he didn’t realize that the otherwise quiet evening he had predicted would soon be turned upside down when a tornado would rip through the base later that night.

The tornado (also sometimes called a “twister”) raced through the Oklahoma City countryside before striking Tinker at 10:22 p.m. The funnel battered buildings and destroyed fifty-four aircraft. Airplanes left outside of hangars were tossed around like toys. Tools and airplane parts became dangerous objects in the fierce wind. After crashing through the base, the tornado disappeared. In the blink of an eye, the storm had caused more than $10 million in damage. The next morning, soldiers surveyed the destruction with amazement. How could the tornado have struck without warning? Nothing like it had ever happened before at Tinker. The US Air Force couldn’t afford for it to happen again.

The following day, Major Ernest Fawbush and Captain Robert Miller were tasked with examining past storms and weather patterns in the area. It was up to them to help find a way for Tinker Air Force Base not to be caught off guard by another tornado.

This wasn’t an easy task. Fawbush and Miller didn’t have access to the computer technology of today. In the 1940s, people relied on hand-drawn weather maps, crude weather-balloon information, and other charts and graphs for their research.

For the next several days, Fawbush and Miller studied past tornado-producing storms in Oklahoma. They hoped to reveal a pattern to the weather statistics they had on file that would let them predict tornadoes. If they could predict storms, the men could provide advance warning to the military bases around the country.

Perhaps Fawbush and Miller could even expand their work to help warn towns and cities. The pair felt a personal responsibility to prevent destruction and save lives.

Tinker Air Force Base sits directly in what Fawbush and Miller would later come to call “Tornado Alley.” The term refers to a strip of land starting in Texas that stretches north through the states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. There are no official boundaries for Tornado Alley. The nickname simply refers to an approximately 500,000-square-mile area within the United States.

There are four elements at work in Tornado Alley that make it a perfect place for twisters to form. The upper atmosphere is home to a strong jet stream—the winds that form between pockets of warm and cold air. While cold, dry air blows down from Canada, warm, dry air travels north from Mexico. Those air masses soon meet the moist air drifting in from the Gulf of Mexico. Because Tornado Alley sits in a lowland region, there are few physical barriers—like mountains—to block or redirect the airflow. As these air masses collide over the entire area of Tornado Alley, they create the perfect recipe for sudden and dangerous storms.

After days of reviewing weather reports, Fawbush and Miller found the pattern they sought. Minutes before each tornado had touched down in the state of Oklahoma, the weather patterns

on the map appeared eerily similar. The two men felt confident they could predict a tornado, but they’d have to wait for another severe storm to put their theory to the test.

And they didn’t have to wait long.

Five days later, on March 25, Fawbush and Miller paid close attention to the weather as another storm brewed nearby. The men recognized the telltale weather patterns that they associated with the birth of a tornado. They had to act.

Fawbush and Miller begged their commanding general, Fred Borum, to issue a tornado forecast for Tinker Air Force Base. Borum resisted. He knew that if he issued the warning and a tornado didn’t touch down, soldiers wouldn’t take future warnings seriously.

The meteorologists were faced with a difficult choice: They could keep quiet and risk even more tornado damage, or they could push the general to issue the tornado warning in hopes of saving lives.

Fawbush and Miller knew exactly what they had to do.

**

Chapter 1The History of Meteorology**

It seems that for as long as humans have been around, they have been intrigued by the weather and how to predict it. Throughout history, many great minds have studied the weather, a practice which came to be known as meteorology.

The first known meteorologist (someone who studies the weather) is thought to have been the Greek philosopher Aristotle.

Aristotle took an interest in big concepts including philosophy and the weather. In 340 BC, he wrote a book titled Meteorologica. It contains one of the earliest explanations of Earth’s atmosphere (the layer of gases that surround planet Earth). However, that wasn’t Aristotle’s only major contribution. His theories that the Earth was round, that the moon orbited the planet, and that Earth consisted of four main elements—-earth, wind, fire, and air—-were widely accepted by astronomers of his time.

Even before Aristotle, the ancient Egyptians believed they could control the weather and often held rituals to summon rain. (These were not always successful.)

Many ancient cultures who lived hundreds of years after Aristotle, and didn’t have access to his writing, believed the weather was controlled by gods.

The Maya living in Central America looked to Chaac, their god of rain, thunder, and lightning. These early Mesoamerican people believed that Chaac carried a lightning ax, and when he struck the clouds, it created thunder and rain.

Between the years AD 300 and 900, the Maya developed their own systems of science, astronomy, architecture, timekeeping, and meteorology. They observed the skies and recorded what they saw over hundreds of years. As time went on, they recognized weather patterns and planetary movements. Soon, the Maya were predicting weather with greater accuracy.

As Aristotle’s Meteorologica was translated to more and more languages, it was used as the basis of meteorology right up to and through the seventeenth century. There were still several inventions coming that would help take weather prediction from a dream to a reality. The first of those important inventions was the barometer. A barometer is a scientific instrument used by meteorologists to measure the rise and fall of atmospheric pressure, which is air pressure within the atmosphere. This tool helps predict the weather by indicating if a storm is going toward or away from a town or city.

…