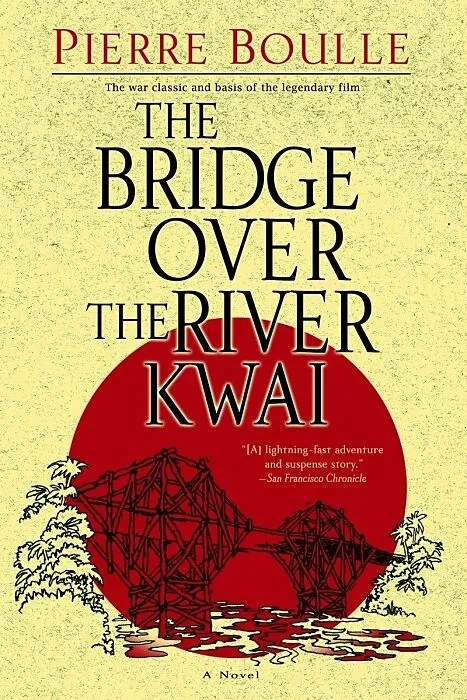

The Bridge over the River Kwai

Beschreibung

Zusatztext [A] lightning-fast adventure and suspense story. San Francisco Chronicle An amazing story . . . jumpy with suspense. The New Yorker A fine story of adventure in which a highly original conception makes a psychologically rich situation out of what co...Format auswählen

- BroschiertCHF 20.00

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Zusatztext [A] lightning-fast adventure and suspense story. San Francisco Chronicle An amazing story . . . jumpy with suspense. The New Yorker A fine story of adventure in which a highly original conception makes a psychologically rich situation out of what could have easily been a simple tale of daring. Chicago Tribune An exciting story of action. The Atlantic Monthly Intelligent and thrilling. New York Post A memorable novel brilliantly conceived and brilliantly written. Harper's Magazine Superb . . . suspenseful. Time Informationen zum Autor Pierre Boulle Klappentext 1942: Boldly advancing through Asia! the Japanese need a train route from Burma going north. In a prison camp! British POWs are forced into labor. The bridge they build will become a symbol of service and survival to one prisoner! Colonel Nicholson! a proud perfectionist. Pitted against the warden! Colonel Saito! Nicholson will nevertheless! out of a distorted sense of duty! aid his enemy. While on the outside! as the Allies race to destroy the bridge! Nicholson must decide which will be the first casualty: his patriotism or his pride. 1 the insuperable gap between east and west that exists in some eyes is perhaps nothing more than an optical illusion. Perhaps it is only the conventional way of expressing a popular opinion based on insufficient evidence and masquerading as a universally recognized statement of fact, for which there is no justification at all, not even the plea that it contains an element of truth. During the last war, saving face was perhaps as vitally important to the British as it was to the Japanese. Perhaps it dictated the behavior of the former, without their being aware of it, as forcibly and as fatally as it did that of the latter, and no doubt that of every other race in the world. Perhaps the conduct of each of the two enemies, superficially so dissimilar, was in fact simply a different, though equally meaningless, manifestation of the same spiritual reality. Perhaps the mentality of the Japanese colonel, Saito, was essentially the same as that of his prisoner, Colonel Nicholson. These were the questions which occupied Major Clipton's thoughts. He, too, was a prisoner, like the five hundred other wretches herded by the Japanese into the camp on the River Kwai, like the sixty thousand English, Australians, Dutch, and Americans assembled in several groups in one of the most uncivilized corners of the earth, the jungle of Burma and Siam, in order to build a railway linking the Bay of Bengal to Bangkok and Singapore. Clipton occasionally answered these questions in the affirmative, realizing, however, that this point of view was in the nature of a paradox; to acquire it one had to disregard all superficial appearances. Above all, one had to assume that the beatings-up, the butt-end blows, and even worse forms of brutality through which the Japanese mentality made itself felt were all as meaningless as the show of ponderous dignity which was Colonel Nicholson's favorite weapon, wielded as a mark of British superiority. But Clipton willingly gave way to this assumption each time his C.O.'s behavior enraged him to such an extent that the only consolation he could find was in a wholehearted objective examination of primary causes. He invariably came to the conclusion that the combination of individual characteristics which contributed to Colonel Nicholson's personality (sense of duty, observance of ritual, obsession with discipline, and love of the job well done were all jumbled together in this worthy human repository) could not be better described than by the single word snobbery. During these periods of feverish investigation he regarded him as a snob, a perfect example of the military snoba type that has been slowly and elaborately built up since the Stone Age and by its traditio...

8220;[A] lightning-fast adventure and suspense story.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

“An amazing story . . . jumpy with suspense.”

–The New Yorker

“A fine story of adventure in which a highly original conception makes a psychologically rich situation out of what could have easily been a simple tale of daring.”

–Chicago Tribune

“An exciting story of action.”

–The Atlantic Monthly

“Intelligent and thrilling.”

–New York Post

“A memorable novel brilliantly conceived and brilliantly written.”

–Harper’s Magazine

“Superb . . . suspenseful.”

–Time

Autorentext

Pierre Boulle

Klappentext

1942: Boldly advancing through Asia, the Japanese need a train route from Burma going north. In a prison camp, British POWs are forced into labor. The bridge they build will become a symbol of service and survival to one prisoner, Colonel Nicholson, a proud perfectionist. Pitted against the warden, Colonel Saito, Nicholson will nevertheless, out of a distorted sense of duty, aid his enemy. While on the outside, as the Allies race to destroy the bridge, Nicholson must decide which will be the first casualty: his patriotism or his pride.

Leseprobe

1

the insuperable gap between east and west that exists in some eyes is perhaps nothing more than an optical illusion. Perhaps it is only the conventional way of expressing a popular opinion based on insufficient evidence and masquerading as a universally recognized statement of fact, for which there is no justification at all, not even the plea that it contains an element of truth. During the last war, “saving face” was perhaps as vitally important to the British as it was to the Japanese. Perhaps it dictated the behavior of the former, without their being aware of it, as forcibly and as fatally as it did that of the latter, and no doubt that of every other race in the world. Perhaps the conduct of each of the two enemies, superficially so dissimilar, was in fact simply a different, though equally meaningless, manifestation of the same spiritual reality. Perhaps the mentality of the Japanese colonel, Saito, was essentially the same as that of his prisoner, Colonel Nicholson.

These were the questions which occupied Major Clipton’s thoughts. He, too, was a prisoner, like the five hundred other wretches herded by the Japanese into the camp on the River Kwai, like the sixty thousand English, Australians, Dutch, and Americans assembled in several groups in one of the most uncivilized corners of the earth, the jungle of Burma and Siam, in order to build a railway linking the Bay of Bengal to Bangkok and Singapore. Clipton occasionally answered these questions in the affirmative, realizing, however, that this point of view was in the nature of a paradox; to acquire it one had to disregard all superficial appearances. Above all, one had to assume that the beatings-up, the butt-end blows, and even worse forms of brutality through which the Japanese mentality made itself felt were all as meaningless as the show of ponderous dignity which was Colonel Nicholson’s favorite weapon, wielded as a mark of British superiority. But Clipton willingly gave way to this assumption each time his C.O.’s behavior enraged him to such an extent that the only consolation he could find was in a wholehearted objective examination of primary causes.

He invariably came to the conclusion that the combination of individual characteristics which contributed to Colonel Nicholson’s personality (sense of duty, observance of ritual, obsession with discipline, and love of the job well done were all jumbled together in this worthy human repository) could not be better described than by the single word snobbery. During these periods of feverish investigation he regarded him as a snob, a perfect example of the military snob—a type that has been slowly and elaborately built up since the Stone Age and by its tradition guaranteed the preservation of th…