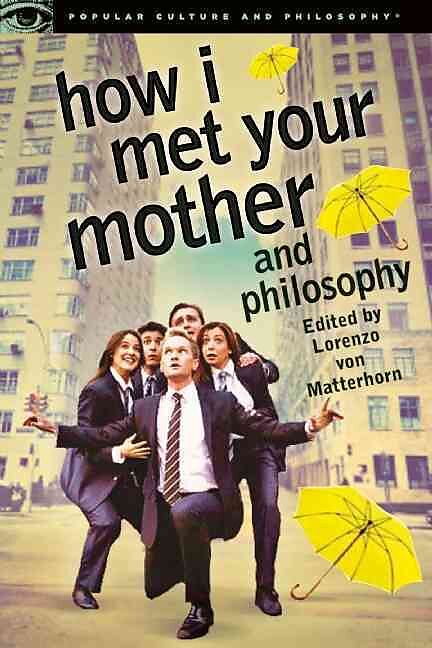

How I Met Your Mother and Philosophy

Beschreibung

Presents a collection of essays by philosophers about the television program "How I Met Your Mother," analyzing the personalities and behavior of its various characters from a moral and philosophical point of view. Autorentext Lorenzo von Matterhorn is the pse...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 34.00

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Presents a collection of essays by philosophers about the television program "How I Met Your Mother," analyzing the personalities and behavior of its various characters from a moral and philosophical point of view.

Autorentext

Lorenzo von Matterhorn is the pseudonym of a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, and Senior Research Associate at Peterhouse College, Cambridge University (UK). He is the author of Between Perception and Action and Aesthetics as Philosophy of Perception (both forthcoming in 2013 from Oxford University Press), and editor of Perceiving the World (Oxford University Press, 2010). Before taking up full-time philosophy he was well known as a movie critic, and served on the jury at several major international film festivals. He lives in Antwerp, Belgium and Cambridge, England.

Klappentext

If you didn't guess that "How I Met Your Mother" is all about the metaphysical mysteries of human existence, you're in for a surprise. Like philosophy itself, "How I Met Your Mother" has everyone thinking. Have you ever wondered why you identify so strongly with Barney despite the fact that he's such a douche? Or why your life story doesn't make sense until you know the ending--or at least, the middle? Or where the Bro Code came from and why it's so powerful? "How I Met Your Mother and Philosophy" answers all these questions and a whole lot more.

Zusammenfassung

Like philosophy itself, "How I Met Your Mother" has everyone thinking. Have you ever wondered why you identify so strongly with Barney despite the fact that he's such a douche? Or why your life story doesn't make sense until you know the ending--or at least, the middle? Or where the Bro Code came from and why it's so powerful? "How I Met Your Mothe

Leseprobe

Excerpt from chapter 1:

Empathy for the Devil: Why on Earth Do We Identify with Barney? by Bence Nanay

Kids, Barney Stinson is the devil. At least, that’s what Ted says in ‘Belly full of turkey’ (season 1, episode 9). And in ‘Brunch’ (season 2, episode 3), he is genuinely surprised that Barney is allowed to enter a church. But even if he is not the devil, he is a truly awful person. Truly. But then why do we all love him so much? More precisely, why is it so tempting to identify or empathize or emotionally engage with him?

Just how awful is Barney? Unspeakably awful. A couple of biographical details:

• He sold a woman (The Bracket, season 3, episode 14)

• He poisoned the drinking water in Lisbon (The goat, season 3, episode 17)

• He has shady dealings with the most oppressive regime on Earth (Chain of screaming, season 3, episode 15)

But maybe it’s just his line of work. We know that Tony Soprano’s job is not exactly charity-work, but we have not problem identifying and emotionally engaging with him. Yet, he is in many ways a choirboy compared to Barney Stinson. Barney can be as awful with his best friends as in his dealings at Goliath National Bank. Again, a few examples:

• When facing the dilemma of landing a much needed job for his ‘best friend’ (who had just been left at the altar) or having an office in a dinosaur-shaped building, he chooses the latter. (Woo girls, season 4, episode 8)

• He takes revenge on the girl who broke his heart many years later by sleeping with her and then never calling her back (Game night, season 1, episode 14)

• Gives a fake apology to Robin, whom he just broke up with, merely in order to score another girl (Playbook, season 5, episode 8)

• Spends years planning his revenge on Marshall for noticing that he has a bit of marinara sauce on his tie (The exploding meatball sub, season 6, episode 20)

• Sets his best friend’s coat on fire (The pineapple incident, season 1, episode 10)

• Pulls a nasty and tactless prank on Robin when he pretends to be Robin’s dad on the phone, whose call he knows she is eagerly awaiting (Disaster averted, season 7, episode 9)

• Actively puts Robin down when she meets Ted’s parents for the first time (Brunch, season 2, episode 3)

• Makes his best friend, Ted believe that Mary, the paralegal is in fact a prostitute, so that he can enjoy how Ted is making a fool of himself. (Mary, the paralegal, season 1, episode 19)

• Stages a one-man show that has one purpose only: to annoy Lily (Stuff, Season 2, episode 16)

• Makes a fool of all his friends, who, unknowingly, help him score with a girl (Playbook, season 5, episode 8)

And we have not even got into the various tricks he uses in order to get girls to come home with him. His behavior is utterly immoral according to the vast majority of existing accounts in moral philosophy. Lily nicely sums it up: he is “the emotional equivalent of a scavenging sewer rat” (Best couple ever, season 2, episode 5). But then why do we like him? Why do we identify with him? Why is he one of the most popular sitcom characters of all time?

Barney is not the first bad character in the history of the genre. In Friends, Joey Tribbiani did some nasty stuff: he burned the prosthetic leg of a girl in the middle of the forest and then drove away. But he loved his friends and would never knowingly screw them. All four characters in Seinfeld did awful things throughout the series, as memorably evidenced by the finale. But Barney takes this to a completely different level of awfulness.

We have a paradox then: how can we identify with and relate to a fictional character, Barney, who is such a terrible person that if we met him in real life, we would probably slap him or leave the room. This paradox needs to be kept apart from the famous ‘paradox of fiction’, the most succinct exposition of which comes not from Hume but from Chandler Bing:

Chandler: Bambi is a cartoon

Joey: You didn’t cry when Bambi’s mother died?

Chandler: Yes, it was very sad when the guy stopped drawing the deer. (Friends, season 6, episode 14)

The paradox of fiction is this: why do we feel strong emotions towards fictional events and characters we know do not exist? The paradox I want to focus on here – we could call it the Barney paradox – is different. It accepts that we feel strong emotions towards fictional characters. But then the question arises which fictional character we feel strong emotions towards? Who is our identification or empathy or emotional engagement directed at? And here comes the paradox: it seems that often we identify or empathize with the least worthy of the fictional characters.

I will go through a couple of possible ways in which one could address this paradox.

Barney is not so bad

Maybe I was just picking out the worst of Barney. And maybe he is more like Joey, who in some respects is not the boyfriend you may want to take home to meet your parents, but in some others has a heart of gold.

There are some stories that point in this direction. In The scorpion and the toad (season 2, episode 2), Barney is allegedly helping Marshall getting over Lily and getting back in the game. But each time Marshall actually has a chance of scoring with a girl, Barney steps in and takes home the girl instead. The title of the episode refers to the Aesop tale about the scorpion who asks the toad to carry him across the river. The toad asks: why would I do that – you’ll sting me and then we’ll both die. But, the scorpion responds, if I sting you, we’ll both die – so why would I sting you? So the toad agrees, but halfway through the scorpion does sting the toad and they both die – that’s just the scorpion’s nature. It should be clear who the scorpion is supposed to stand for here.

So far, this is a pretty damning statement about Barney, but that is not the full story. This happened at …