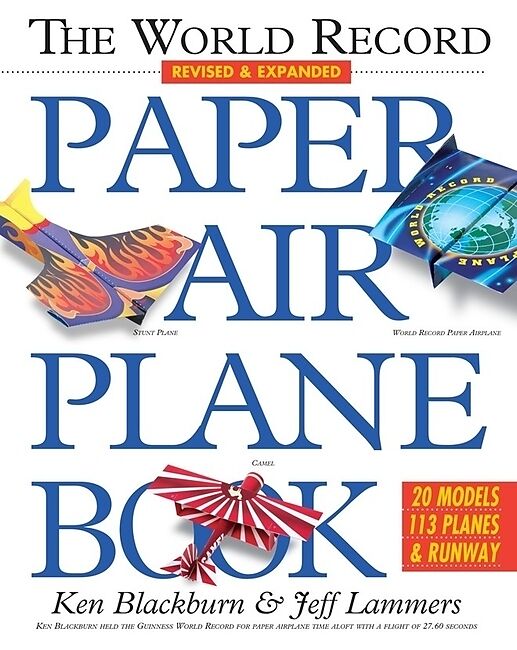

The World Record Paper Airplane Book

Beschreibung

Provides resources for beginners and experienced paper airplane fliers alike with a total of 20 models and 112 flyers, ready to pull out and fold. This book features a text section with photos and information on aerodynamics, competitions, and designing your o...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 21.10

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Provides resources for beginners and experienced paper airplane fliers alike with a total of 20 models and 112 flyers, ready to pull out and fold. This book features a text section with photos and information on aerodynamics, competitions, and designing your own high-performing models.

Autorentext

Ken Blackburn is an aerospace engineer and four-time Guinness World Record holder for paper airplane time aloft (last record 27.60 seconds). He works for the Air Force doing aeronautical research in Florida.

Jeff Lammers is an engineer and entrepreneur based in Colorado. He flies small planes in his spare time.

Klappentext

It's the classic, world's bestselling paper airplane book, grounded in the aerodynamics of paper and abounding with fun. The World Record Paper Airplane Book raises paper airplane making to a unique, unexpected art. This new edition boasts four brand-new models: Stiletto, Spitfire, Galactica, and Sting Ray. Added to its hangar of proven fliers-including Valkyrie, Hammerhead, Vortex, Condor, Pterodactyl, and, of course, the famous World Record Paper Airplane-that makes twenty airworthy designs. Each is swathed in all-new, attention-grabbing graphics and is ready to tear out, fold, and fly. There are at least five models for each design and all-important instructions for how to adjust and throw each plane for best flight. But the planes are just the beginning. The book features tons of cool information on aerodynamics, competitions, and designing your own high-performing models. Readers will learn why paper airplanes fly (and why they crash), the history of Ken Blackburn's world record, and how to organize and win contests. Also included is a flight log and pull-out runway for practicing accuracy.

Leseprobe

History of the World Record Paper Airplane

WHEN I WAS ABOUT EIGHT years old, I made one of my frequent trips to the aviation section of the library in Kernersville, North Carolina, and checked out a book that included instructions for a simple square paper airplane. I found that it flew better than the paper darts I was used to making. Thrown straight up, it reached much higher altitudes.

To the dismay of my teachers, I folded many of these planes, experimenting with changes to the original design. (One of the beauties of paper airplanes is that they are perfectly suited to trial and error testing. If one doesn’t work, it’s cheap and easy to start over.) One of my designs would level off at the peak of its climb and then start a slow downward glide. Sometimes, with the help of rising air currents, I achieved flights lasting nearly a minute and covering about 1,000 feet.

In 1977, I received a Guinness Book of World Records as a gift. Naturally the first thing I turned to was the aviation section. The paper airplane “time aloft” record was 15 seconds, set by William Pryor in 1975. It dawned on me that my planes (without help from the wind) were flying at close to world record times. On my next outing, I timed the best flights. They weren’t quite long enough to break the record, but with a little work I thought I could do it.

With this goal in mind, I refined my plane designs and worked on my throw. Many people are surprised to learn that I consider the throw to be almost as important as the plane itself. The faster the throw, the higher the airplane goes and, therefore, the longer the flight.

In 1979, when I was a junior in high school, I made an official attempt at the world record. The record was described in the Guinness Book as time “over level ground,” so I chose the school’s baseball field as my staging ground. One afternoon, with my teachers as timers and a reporter on hand from the Winston- Salem Journal, I let my favorite square plane fly.With the help of the wind, I made a flight of 24.9 seconds, and was sure I had flown right into the pages of history.

Unfortunately, the letter I received back from Guinness Superlatives, Ltd., wasn’t quite what I had hoped for.They informed me that the flight had to be performed indoors.

The next year, I worked part-time at Reynolds Coliseum in Winston-Salem, parking cars and moving equipment. In my time off, I had access to the largest indoor paper airplane practice arena I would ever need. My best flights yielded times of over 17 seconds, and I knew the record was mine for the taking, but I got sidetracked by college applications.

A Second Attempt

August of 1981 was the beginning of four years of aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University. I lived on the sixth then the eighth floor, perfect airplane launching pads (even though throwing objects from dorm windows was strictly prohibited). I made planes from every paper product available— from pizza boxes to computer punch cards—in many bizarre shapes, and soon infected the dorm with plane-flying fever.

Still, it wasn’t until my junior year that my friends began encouraging me to make another stab at the world record, and I finally decided to give it a try. I practiced several times at the school coliseum, keeping the best plane from my sessions, nicknamed “Old Bossy,” for the record attempt. Old Bossy was regularly achieving times over 17 seconds, well above the 15-second record.

A friend arranged for a reporter from the school newspaper to meet us at the coliseum. I made a few warm-up throws, and then reached for Old Bossy.With a mighty heave, I sent the plane hurtling into the upper reaches of the coliseum . . . and directly into a cluster of speakers near the ceiling. I was devastated. My best plane, Old Bossy, gone forever.

My roommate handed me a piece of ordinary copier paper and I quickly made another airplane. My second throw with the new plane was the best of the afternoon at 16.89 seconds. It beat the old record, but I knew I could have done better with Old Bossy. I sent Guinness the newspaper article, signatures of the witnesses, and Old Bossy’s replacement. This time Guinness responded with the letter I’d been waiting for.

After graduation, I went to work for an aerospace company— McDonnell Douglas in St. Louis, Missouri. In the summer of 1987, I was finishing a job on the F-18 Hornet, when I got an unexpected call from California. A television production company was putting together a series featuring people attempting to break world records.Would I be interested in trying to reset my record? I didn’t have to think long before replying with a definite yes. The filming was only a few weeks away and I usually needed at least a month to get my throwing arm in shape, so I started practicing immediately.

Round Three

With my best practice airplanes packed in an old shoe box, I set out on my allexpense- paid extravaganza to Milwaukee. It turned out that Tony Feltch, the distance record holder for paper airplanes, was also there, trying to beat his record, and that we’d be making our attempts in the Milwaukee Convention Center.

Tony went first and, after only a few throws, broke his old record, achieving a distance of nearly 200 feet. Additional filming and interviews with Tony dragged on for hours, leaving me on the sidelines, sweating bullets.

Finally, it was my turn. I picked out my best plane from practice, and got the nod from the producer that the cameras were rolling. I heaved the airplane upward, and watched it float down. The official called out a time of 15.02 seconds. I concentrated harder on my second throw, but was again rewarded with a time of only 15.47 seconds. Suddenly it struck me that I might not be able to reset the record. Even in good condition, my arm lasts for only a couple of world record throws in any one day.

I made my third throw with everything I had. (I estimate that these throws leave my hand at a…