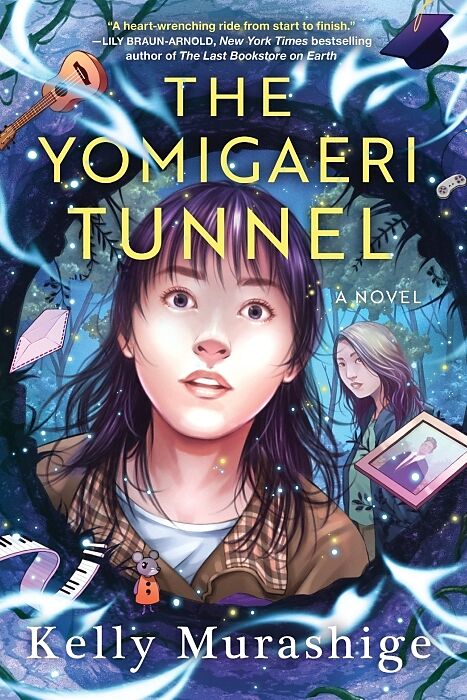

The Yomigaeri Tunnel

Beschreibung

This speculative coming-of-age YA novel follows a teenager as she undertakes a magical journey to bring her deceased childhood friend back to life. A poignant quest for hope with original, fantastical twists, perfect for fans of Dustin Thao and Ann Liang. Bran...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 22.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

This speculative coming-of-age YA novel follows a teenager as she undertakes a magical journey to bring her deceased childhood friend back to life. A poignant quest for hope with original, fantastical twists, perfect for fans of Dustin Thao and Ann Liang. Brand new high-school graduate Monika can’t bring herself to celebrate her last summer before college. Instead, she’s still grieving the loss of the one classmate who didn’t make it to graduation, a boy named Shun with whom she had a complicated relationship. Then, during her final Japanese Club meeting, Monika hears about the Yomigaeri Tunnel--according to a local urban legend, those who venture into this mythological passageway are subjected to a terrifying journey to confront their worst fears, hidden secrets, and maybe even literal ghosts. The tunnel is said to reward anyone who makes it through with the ability to resurrect one soul from the dead. Monika jumps at the chance to bring back Shun, but she soon discovers that she isn’t the only one to have heard the legend. Sharp-tongued and fierce Shiori is hellbent on reviving her mother and won’t let anyone stop her. This emotional, offbeat, utterly charming read-in-one-sitting book about the anguish and joys of being a teenager should come with a box of tissues.

Autorentext

Kelly Murashige

Klappentext

Grieving the loss of her classmate and childhood friend, eighteen-year-old Monika searches for a legendary tunnel, said to resurrect one soul from the dead for anyone brave enough face their inner demons.

Leseprobe

Chapter One

Most Likely to Have a Mental Breakdown in the Bathroom

You know how they say there’s a light at the end of the tunnel? Well, when I was little, I always thought it was life. There’s a life at the end of the tunnel. In my childish mind, where stuffed animals could talk and unicorns were real and rainbows were more than mere tricks of the light, that was what we were being promised. We had to keep going, no matter how bad life seemed, because someday, we would reach the end of our darkness and be given a whole new life.

I believed a lot of dumb things when I was little, including the idea that swallowing a watermelon seed meant you were going to grow an entire fruit in your stomach, but I don’t think hoping for life at the end of a tunnel is stupid. If you’re sick of being the person you are, if you hate the people you’re supposed to love and love the people you’re supposed to hate, if you look in the mirror every morning and struggle to recognize the ghost reflected back at you, it feels like the only answer is to start a new life. How is some light supposed to help you? Wouldn’t it be better if there could be life at the end of a tunnel?

Well, I’m older now. Too old to believe in all those childish fantasies. And I’ve decided I don’t need the life to be literal. Just becoming someone else would be enough.

“Monika.”

I raise my head. Natsuki, the former president of the Japanese Club, watches me through his thick-rimmed glasses, a cup of tea in his hands. We may have graduated together yesterday, but he already seems years ahead of me. Stanford-bound, just as he’s been dreaming since he learned the difference between college and collage, he was always going to either wind up on some 30 Under 30 list or have a nervous breakdown. Par for the course for kids of our generation, really. I’m just glad he’s willing to keep himself chained to our high school’s Japanese Club long enough to organize and host this celebratory going-away brunch rather than leaving it to some of our classmates who—and I’m just being honest here—probably still don’t know the difference between college and collage.

“Sorry,” I say. “Did you need something?”

“No, nothing.” Natsuki gives me a tight smile over the lip of his cup. “I just wanted to check up on you. You seem to be deep in thought.”

I return his tense smile. “I’m just musing quietly.”

It was impossible to think at that brunch table. Not just because some of the others were trying to see which of them could chug their miso soup the fastest, though that was an absolutely horrifying, mind-numbing, I-can’t-believe-they-gave-you-a-diploma experience, but because everyone seemed so alive. And I just couldn’t handle that.

So I excused myself for a moment, not that anyone had been paying me any attention, and sat on one of the lonely chairs by the glass-door exit. Cue quiet musing.

“Ah. Understandable.” Natsuki glances over at the tables, takes a long sip of tea, then looks back at me. “I should check in with the Cultural Center’s head of operations.”

Probably a good idea. Natsuki may be just about the most well-mannered, levelheaded person I’ve ever met, but as the final act of his presidency, he invited the Japanese Clubs from some of the nearby schools too, and those kids can get rowdy, to say the least. Earlier today, two fellow grads were chastised for trying to steal the Noh masks from the Japanese Cultural Center’s main display.

We were going to give them back, one said. We just wanted to try them on.

Uh-huh, Natsuki said. Did you just graduate from high school? Or preschool?

**

“Please tell her we’re sorry,” I say.

He grimaces. “Will do.” After taking a peek at his phone, he glances at me, his expression cool. “Don’t be a stranger, okay?”

I try not to read too much into it. He’s only saying that because he has to, the type to seek people out on social media and follow them even if they never follow him back, wish them a happy birthday even if they never respond, and message them whenever he hears they’ve won an award or gotten an internship even if they leave him on read.

Before, our interactions were limited to the brief, obligatory exchange of tight-lipped smiles at club meetings.

Then Shun died, and everything changed. Everyone changed. Our class both grew together and fell apart, and now, everyone’s leaving again. Without him.

I’m convinced no one just dies. Even if they’re alone when it happens, even if no one has spoken to them in years, even if they think no one cares, one person’s death affects so many.

I watch, silent, as Natsuki makes a beeline for the head of operations. She stands in the little cubicle off to the side, the giant glass window giving her a perfect view of the chaos she’s unleashed upon her beloved Cultural Center.

I reluctantly edge my way over to where the others are gathered. Avoiding the gazes of my classmates, I survey the students from the other schools’ Japanese Clubs, my eyes snagging on the guy wearing a bright yellow shirt with a bunny-ear-toting anime girl, then the girl standing off to the side, her delicate fingers picking at the skin on her lips.

“If you try to ask for another color,” Anime Shirt says, his eyes wide, “he grabs you by the collar and drags you into the underworld.”

One girl tilts her head. “Then how are you supposed to escape him?”

“You have to either ignore him or say you don’t want any kind of paper, then leave before he gets angry.”

“He’s a vengeful spirit. I’m pretty sure he’d be angry already.”

Another girl narrows her eyes. “How are you supposed to ignore a spirit in the bathroom? There’s no way I’m doing my business when there’s a guy floating above me.”

The first girl frowns. “I thought the spirit that haunted the bathroom was a girl.”

An…