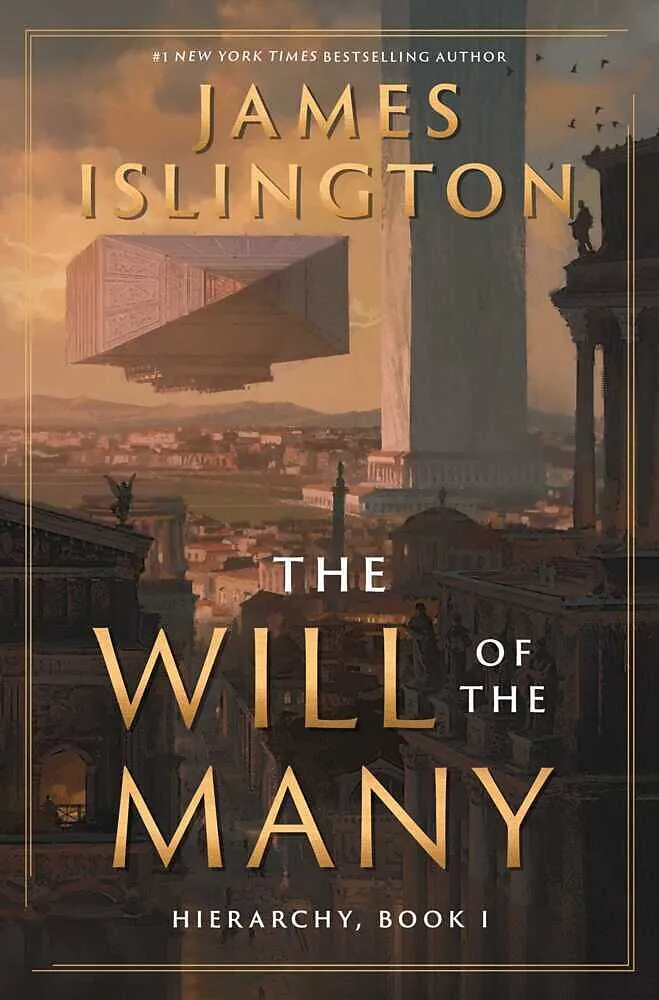

The Will of the Many

Beschreibung

At the elite Catenan Academy, where students are prepared as the future leaders of the Hierarchy empire, the curriculum reveals a layered set of mysteries which turn murderous in this new fantasy by bestselling author of The Licanius Trilogy, James Islington.V...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 39.90

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 18.40

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 27.10

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

At the elite Catenan Academy, where students are prepared as the future leaders of the Hierarchy empire, the curriculum reveals a layered set of mysteries which turn murderous in this new fantasy by bestselling author of The Licanius Trilogy, James Islington.Vis, the adopted son of Magnus Quintus Ulcisor, a prominent senator within the Hierarchy, is trained to enter the famed Catenan Academy to help Ulciscor learn what the hidden agenda is of the remote island academy. Secretly, he also wants Vis to discover what happed to his brother who died at the academy. He's sure the current Principalis of the academy, Quintus Veridius Julii, a political rival, knows much more than he's revealing.The Academy's vigorous syllabus is a challenge Vis is ably suited to meet, but it is the training in the use of Will, a practice that Vis finds abhorrent, that he must learn in order to excel at the Academy. Will-a concept that encompasses their energy, drive, focus, initiative, ambition, and vitality-can be voluntarily "ceded" to someone else. A single recipient can accept ceded Will from multiple people, growing in power towards superhuman levels. Within the hierarchy your level of Will, or legal rank, determines how you live or die. And there are those who are determined to destroy this hierarchal system, as well as those in the Academy who use it to gain dominance in internationally bestselling author James Islington's wonderfully crafted new epic fantasy series.

Autorentext

James Islington is the bestselling author of The Will of the Many (the first novel in the Hierarchy series), as well as the Licanius Trilogy (beginning with The Shadow of What Was Lost). **He has sold more than two million books, and his work has been translated into seventeen different languages. He lives on the Mornington Peninsula in Victoria, Australia, with his wife and two children.

Leseprobe

Chapter I

I

I AM DANGLING, AND IT is only my father’s blood-slicked grip around my wrist that stops me from falling.

He is on his stomach, stretched out over the rocky ledge. His muscles are corded. Sticky red covers his face, his arms, his clothes, everything I can see. Yet I know he can pull me up. I do everything I can not to struggle. I trust him to save me.

He looks over my shoulder. Into the inky black. Into the darkness that is to come.

“Courage,” he whispers. He pours heartbreak and hope into the word.

He lets go.

“I KNOW I’M ALWAYS TELLING you to think before you act,” says the craggy-faced man slouching across the board from me, “but for the game to progress, Vis, you do actually have to move a gods-damned stone.”

I rip my preoccupied gaze from the cold silver that’s streaming through the sole barred window in the guardroom. Give my opponent my best irritated glare to cover the sickly swell of memory, then force my focus again to the polished white and red triangles between us. The pieces glint dully in the light of the low-burning lantern that sits on the shelf, barely illuminating our contest better than the early evening’s glow from outside.

“You alright?”

“Fine.” I see Hrolf’s bushy grey eyebrows twitch in the corner of my vision. “I’m fine, old man. Just thinking. Sappers haven’t got me yet.” No heat to the words. I know the way his faded brown eyes crinkle with concern is genuine. And I know he has to ask.

I’ve been working here almost a year longer than him, so he’s wondering again whether my mind is losing its edge. Like his has been for a while, now.

I ignore his worry and assess the Foundation board, calculating what the new red formation on the far side means. A feint, I realise immediately. I ignore it. Shift three of my white pieces in quick succession and ensure the win. Hrolf likes to boast about how he once defeated a Magnus Quartus, but against me, it’s never a fair match. Even before the Hierarchy—or the Catenan Republic, as I still have to remind myself to call them out loud—ruled the world, Foundation was widely considered the perfect tool for teaching abstract strategic thinking. My father ensured I was exposed to it young, often, and against the very best players.

Hrolf glowers at the board, then me, then at the board again.

“Lost concentration. You took too long. Basically cheating,” he mutters, disgusted as he concedes the game. “You know I beat a Magnus Quartus once?”

My reply is interrupted by a hammering at the thick stone entrance. Hrolf and I stand, game forgotten. Our shift isn’t meant to change for hours yet.

“Identify yourself,” calls Hrolf sharply as I step across to the window. The man visible through the bars is well-dressed, tall and with broad shoulders. In his late twenties, I think. Moonlight shines off the dark skin of his close-shaven scalp.

“Sextus Hospius,” comes the muffled reply. “I have an access seal.” Hospius looks at the window, spotting my observation of him. His beard is black, trimmed short, and he has serious, dark brown eyes that lend him a handsome intensity. He leans over and presses what appear to be official Hierarchy documents against the glass.

“We weren’t told to expect you,” says Hrolf.

“I wouldn’t have known to expect me until about thirty minutes ago. It’s urgent.”

“Not how it works.”

“It is tonight, Septimus.” No change in expression, but the impatient emphasis on Hrolf’s lower status is unmistakeable.

Hrolf squints at the door, then walks over to the thin slot set in the wall beside it, tapping his stone Will key to it with an irritated, sharp click. The hole on our side seals shut. Outside, Hospius notes the corresponding new opening in front of him, depositing his documentation. I watch closely to ensure he adds nothing else.

Hrolf waits for my nod, then opens our end again to pull out Hospius’s pages, rifling through them. His mouth twists as he hands them to me. “Proconsul’s seal” is all he says.

I examine the writing carefully; Hrolf knows his work, but here among the Sappers it pays to check things twice. Sure enough, though, there’s full authorization for entry from Proconsul Manius himself, signed and stamped. Hospius is a man of some importance, apparently, even beyond his rank: he’s a specialised agent, assigned directly by the Senate to investigate an irregularity in last year’s census. Cooperation between the senatorial pyramids of Governance—Hospius’s employers, who oversee the Census—and Military, who are in charge of prisons across the Republic, is allowing Hospius access to one of the prisoners here for questioning.

“Looks valid,” I agree, understanding Hrolf’s displeasure. This paperwork allows our visitor access to the lowest level. It’s cruel to wake the men and women down there mid-sentence.

Hrolf takes the page with Manius’s seal on it back from me and slides it into the outer door’s thin release slot. The proconsul’s Will-imbued seal breaks the security circuit just as effectively as Hrolf’s key, and the stone door grinds smoothly into the wall, a gust of Letens’s bitter night air slithering through the opening to herald Hospius’s imposing form. Inside, the man sheds his fine blue cloak and tosses it casually over the back of a nearby chair, flashing what he probably imagines is a charming smile at the two of us. Hrolf sees a man taking liberties with his space, and curbs a scowl as he snaps Hospius’s seal with more vigour than is strictly necessary, releasing its Will and letting the door glide shut again.

I se…