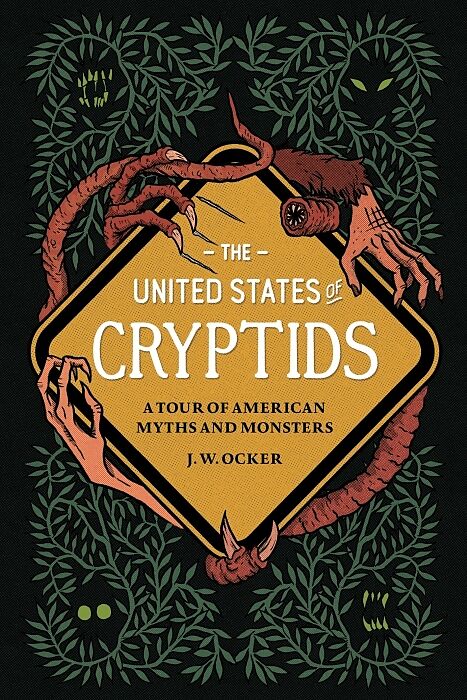

The United States of Cryptids

Beschreibung

Informationen zum Autor J. W. (Jason) Ocker is an Edgar Award-winning travel writer, novelist, and blogger. His previous books include Poe-Land , A Season with the Witch , and Cursed Objects . He is also the creator of the blog and podcast OTIS: Odd Things I'v...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 22.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Informationen zum Autor J. W. (Jason) Ocker is an Edgar Award-winning travel writer, novelist, and blogger. His previous books include Poe-Land , A Season with the Witch , and Cursed Objects . He is also the creator of the blog and podcast OTIS: Odd Things I've Seen (oddthingsiveseen.com), where he chronicles his visits to oddities around the world. Klappentext "A guide to cryptids of the United States and the local communities that celebrate them"-- Leseprobe Guaranteed to See a Cryptid or Your Money Back Bigfoot exists: definitely, demonstrably, unequivocally. So do lake dinosaurs, monster cats, jet-sized birds, lizard-people, fish-people, wolf-people, moth-people, frog-people, and goat-people. All cryptids exist. Let me prove it to you. Wait, nolet me show them to you. But first: What the heck's a cryptid? A cryptid is a creature or species whose existence is scientifically unproven. Maybe it's been witnessed or rumored to exist, maybe it's even been caught on video, but there is no definitive physical evidence to examine: no body to dissect, no remains to analyze. Scientists place those creatures in the category of fantasy instead of zoology. Cryptozoologists, though, who study and pursue cryptids, place them in the entirely separate category of cryptozoology. While the fantastical Mothman and the Jersey Devil may be the first cryptids you think of, a cryptid can be as comparatively mundane as a New England panther or an American lion; animals that once existed but are now believed by the scientific establishment to be extinct. Sometimes these animals are even discovered: the coelacanth, a fish thought to have gone extinct in the age of the dinosaurs, was discovered alive in 1938. A cryptid can even be an ordinary animal that is supposedly thriving where it couldn't be, like a population of alligators in the Manhattan sewers, or freshwater octopuses. At least, that's the traditional definition of a cryptid. Since cryptozoology was established in its modern form in the fifties, the definition has widened to encompass even more fantastical creatures as more people grow interested in the topic. This includes extraterrestrial entities, creatures from folklore such as mermaids and gnomes, sentient non-humans like the Menehune of Hawaii, and even (possibly) robots. This expanding definition of cryptid isn't just because cryptozoology fans are a welcoming lot. It's because cryptid has become synonymous with monster, of any kind. Cryptid fans love monsters, and pop culture cryptozoology is basically Pok.mon: we want to collect all the monster stories, and we want the widest variety of them in our collection as possible. It's a messy word, cryptid. But that's what makes it fun. Most of us who heart cryptids are fine with that imprecision and aren't overly invested in the -ology part of cryptozoology. We don't camp out for weeks in dense forests knocking on trees and scrounging for bigfoot scat. We don't charter boats and rent side-scan sonar systems to scrutinize lake bottoms for water monsters. Unlike cryptozoologists, we aren't trying to scientifically prove the existence of cryptidswe just love the idea of them; we love the stories. And, whatever you think about cryptids, the stories are true. You many disbelieve that a lizard man attacked a car in a South Carolina swamp in the summer of 1988, but the Lizard Man mania is irrefutably documented. In other words, the story is true, regardless of whether the Lizard Man itself is real. But I promised to show you cryptids, not just tell you about them. We're going to focus on these fantastic beasts where we can actually find them: in the towns that claim and celebrate them, that hallow the ground of the sighting, that tie their local cryptid to their identity and geography, and that capitalize on them economically. And for whatever reason, America does cryptotourism best and biggest...

Autorentext

J. W. (Jason) Ocker is an Edgar Award-winning travel writer, novelist, and blogger. His previous books include Poe-Land, A Season with the Witch, and Cursed Objects. He is also the creator of the blog and podcast OTIS: Odd Things I’ve Seen (oddthingsiveseen.com), where he chronicles his visits to oddities around the world.

Klappentext

"A guide to cryptids of the United States and the local communities that celebrate them"--

Zusammenfassung

Come and meet the monsters in our midst, from bigfoot to batsquatch and beyond!

Leseprobe

Guaranteed to See a Cryptid or Your Money Back

Bigfoot exists: definitely, demonstrably, unequivocally. So do lake dinosaurs, monster cats, jet-sized birds, lizard-people, fish-people, wolf-people, moth-people, frog-people, and goat-people. All cryptids exist. Let me prove it to you. Wait, no—let me show them to you. But first: What the heck’s a cryptid?

A cryptid is a creature or species whose existence is scientifically unproven. Maybe it’s been witnessed or rumored to exist, maybe it’s even been caught on video, but there is no definitive physical evidence to examine: no body to dissect, no remains to analyze. Scientists place those creatures in the category of fantasy instead of zoology. Cryptozoologists, though, who study and pursue cryptids, place them in the entirely separate category of cryptozoology. While the fantastical Mothman and the Jersey Devil may be the first cryptids you think of, a cryptid can be as comparatively mundane as a New England panther or an American lion; animals that once existed but are now believed by the scientific establishment to be extinct. Sometimes these animals are even discovered: the coelacanth, a fish thought to have gone extinct in the age of the dinosaurs, was discovered alive in 1938. A cryptid can even be an ordinary animal that is supposedly thriving where it couldn’t be, like a population of alligators in the Manhattan sewers, or freshwater octopuses.

At least, that’s the traditional definition of a cryptid. Since cryptozoology was established in its modern form in the fifties, the definition has widened to encompass even more fantastical creatures as more people grow interested in the topic. This includes extraterrestrial entities, creatures from folklore such as mermaids and gnomes, sentient non-humans like the Menehune of Hawaii, and even (possibly) robots. This expanding definition of cryptid isn’t just because cryptozoology fans are a welcoming lot. It’s because cryptid has become synonymous with monster, of any kind. Cryptid fans love monsters, and pop culture cryptozoology is basically Pok.mon: we want to collect all the monster stories, and we want the widest variety of them in our collection as possible.

It’s a messy word, cryptid. But that’s what makes it fun. Most of us who heart cryptids are fine with that imprecision and aren’t overly invested in the -ology part of cryptozoology. We don’t camp out for weeks in dense forests knocking on trees and scrounging for bigfoot scat. We don’t charter boats and rent side-scan sonar systems to scrutinize lake bottoms for water monsters. Unlike cryptozoologists, we aren’t trying to scientifically prove the existence of cryptids—we just love the idea of them; we love the stories. And, whatever you think about cryptids, the stories are true. You many disbelieve that a lizard man attacked a car in a South Carolina swamp in the summer of 1988, but the Lizard Man mania is irrefutably documented. In other words, the story is true, regardless of whether the Lizard Man itself is real.

But I promised to show you cryptids, not just tell you about them. We’re going to focus on these fantastic beasts where we can actually find them: in the towns that claim and celebrate them, that hallow the ground of the sighting, that tie their local cryptid to their i…