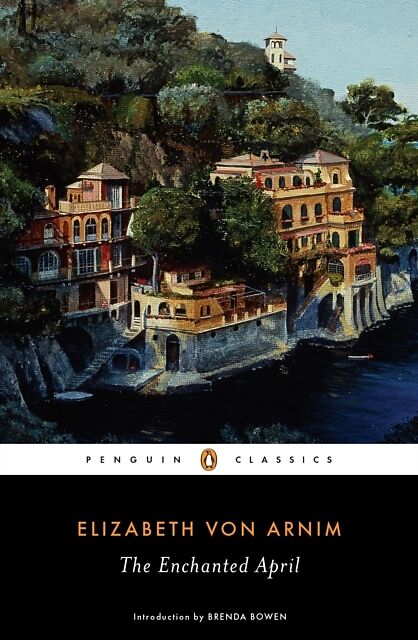

The Enchanted April

Beschreibung

The charming, slyly comic novel of romantic longing and transformation that inspired the Oscar-nominated film Four very different women, looking to escape dreary London for the sunshine of Italy, take up an offer advertised in the Times for a “small medi...Format auswählen

- Poche format BCHF 20.00

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

The charming, slyly comic novel of romantic longing and transformation that inspired the Oscar-nominated film Four very different women, looking to escape dreary London for the sunshine of Italy, take up an offer advertised in the Times for a “small medieval Italian Castle on the shores of the Mediterranean to be let furnished for the month of April.” As each blossoms in the warmth of the Italian spring, quite unexpected changes occur. An immediate bestseller upon its first publication, in 1922, The Enchanted April set off a craze for tourism to the Italian Riviera that continues today. Published here to coincide with a contemporary retelling, Enchanted August by Brenda Bowen, it’s a witty ensemble piece and the perfect romantic rediscovery for fans of Jess Walter’s Beautiful Ruins and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love as well as of Downton Abbey and the hit movie The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,500 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

ldquo;This delicious confection will work its magic on all.” —Daily Telegraph

“Extraordinarily well-written . . . It is witty, human, often very beautiful.” —Punch

“Brims with magic and laughter.” —The Guardian

“[One] of the wittiest novels in the English language . . . The ultimate renter’s novel: a month in and out of a gorgeous place where extraordinary things happen; then let someone else deal with the plumbing . . . It’s a confection, it’s a dream, it’s a fleeting April romance, but oh, how hard to get this story out of your head. . . . No one can come away from this April without thinking, even for just a moment, that the course of true love, unsmooth as it may run, is certainly worth taking.” —Brenda Bowen, author of Enchanted August, from the Introduction

Autorentext

Elizabeth von Arnim (1866–1941), a cousin of the writer Katharine Mansfield and a lover of H. G. Wells, wrote more than twenty books. Born in Australia, she spent most of her childhood in England and lived also in Germany, Switzerland, and France. She moved to the United States at the start of World War II and died in Charleston, South Carolina.

Brenda Bowen (introducer) is the author of the novel Enchanted August, a contemporary reimagining of The Enchanted April set in Maine. A former children’s book publisher, and now a literary agent, she has written more than forty books under the name Margaret McNamara. She lives in New York.

Leseprobe

One

It began in a woman’s club in London on a February afternoon – an uncomfortable club, and a miserable afternoon – when Mrs Wilkins, who had come down from Hampstead to shop and had lunched at her club, took up The Times from the table in the smoking-room, and running her listless eye down the Agony Column saw this:

To Those who Appreciate Wistaria and Sunshine. Small mediaeval Italian Castle on the shores of the Mediterranean to be let Furnished for the month of April. Necessary servants remain. Z, Box 1,000, The Times.

That was its conception; yet, as in the case of many another, the conceiver was unaware of it at the moment.

So entirely unaware was Mrs Wilkins that her April for that year had then and there been settled for her that she dropped the newspaper with a gesture that was both irritated and resigned, and went over to the window and stared drearily out at the dripping street.

Not for her were mediaeval castles, even those that are specially described as small. Not for her the shores in April of the Mediterranean, and the wistaria and sunshine. Such delights were only for the rich. Yet the advertisement had been addressed to persons who appreciate these things, so that it had been, anyhow, addressed too to her, for she certainly appreciated them; more than anybody knew; more than she had ever told. But she was poor. In the whole world she possessed of her own only ninety pounds, saved from year to year, put by carefully pound by pound, out of her dress allowance. She had scraped this sum together at the suggestion of her husband as a shield and refuge against a rainy day. Her dress allowance, given her by her father, was £100 a year, so that Mrs Wilkins’s clothes were what her husband, urging her to save, called modest and becoming and her acquaintance to each other, when they spoke of her at all, which was seldom for she was very negligible, called a perfect sight.

Mr Wilkins, a solicitor, encouraged thrift, except that branch of it which got into his food. He did not call that thrift, he called it bad housekeeping. But for the thrift which, like moth, penetrated into Mrs Wilkins’s clothes and spoilt them, he had much praise. ‘You never know,’ he said, ‘when there will be a rainy day, and you may be very glad to find you have a nest-egg. Indeed we both may.’

Looking out of the club window into Shaftesbury Avenue – hers was an economical club, but convenient for Hampstead, where she lived, and for Shoolbred’s where she shopped – Mrs Wilkins, having stood there some time very drearily, her mind’s eye on the Mediterranean in April, and the wistaria, and the enviable opportunities of the rich, while her bodily eye watched the really extremely horrible sooty rain falling steadily on the hurrying umbrellas and splashing omnibuses, suddenly wondered whether perhaps this was not the rainy day Mellersh – Mellersh was Mr Wilkins – had so often encouraged her to prepare for, and whether to get out of such a climate and into the small mediaeval castle wasn’t perhaps what Providence had all along intended her to do with her savings. Part of her savings, of course; perhaps quite a small part. The castle, being mediaeval, might also be dilapidated, and dilapidations were surely cheap. She wouldn’t in the least mind a few of them, because you didn’t pay for dilapidations which were already there; on the contrary – by reducing the price you had to pay they really paid you. But what nonsense to think of it . . .

She turned away from the window with the same gesture of mingled irritation and resignation with which she had laid down The Times, and crossed the room towards the door with the intention of getting her mackintosh and umbrella and fighting her way into one of the overcrowded omnibuses and going to Shoolbred’s on her way home and buying some soles for Mellersh’s dinner – Mellersh was difficult with fish and liked only soles, except salmon – when she beheld Mrs Arbuthnot, a woman she knew by sight as also living in Hampstead and belonging to the club, sitting at the table in the middle of the room on which the newspapers and magazines were kept, absorbed, in her turn, in the first page of The Times.

Mrs Wilkins had never yet spoken to Mrs Arbuthnot, who belonged to one of the various church sets, and who analysed, classified, divided and registered the poor; whereas she and Mellersh, when they did go out, went to the parties of impressionist painters, of whom in Hampstead there were many. Mellersh had a sister who had married one of them and lived up on the Heath, and because of this alliance Mrs Wilkins was drawn into a circle which was highly unnatural to her, and she had learned to dread pictures. She had to …