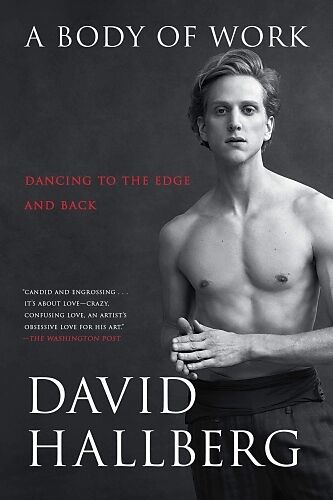

A Body of Work

Beschreibung

Autorentext David Hallberg is a Principal Dancer with American Ballet Theatre in New York. He was the first American to join the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow as a Principal Dancer. He continues to dance around the world and is a Resident Guest Artist with The Aust...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 24.00

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Autorentext

David Hallberg is a Principal Dancer with American Ballet Theatre in New York. He was the first American to join the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow as a Principal Dancer. He continues to dance around the world and is a Resident Guest Artist with The Australian Ballet. He has also started the David Hallberg Scholarship, mentoring young aspiring boys in a career in ballet, and the Innovation Initiative, a platform for emerging choreographers, both at American Ballet Theatre. A Body of Work is his first book.

Klappentext

David Hallberg, the first American to join the famed Bolshoi Ballet as a principal dancer and the dazzling artist The New Yorker described as “the most exciting male dancer in the western world,” presents a look at his artistic life—up to the moment he returns to the stage after a devastating injury that almost cost him his career.

Beginning with his real-life Billy Elliot childhood—an all-American story marred by intense bullying—and culminating in his hard-won comeback, Hallberg’s “moving and intelligent” (Daniel Mendelsohn) memoir dives deep into life as an artist as he wrestles with ego, pushes the limits of his body, and searches for ecstatic perfection and fulfillment as one of the world’s most acclaimed ballet dancers.

Rich in detail ballet fans will adore, Hallberg presents an “unsparing…inside look” (The New York Times) and also reflects on universal and relatable themes like inspiration, self-doubt, and perfectionism as he takes you into daily classes, rigorous rehearsals, and triumphant performances, searching for new interpretations of ballet’s greatest roles. He reveals the loneliness he felt as a teenager leaving America to join the Paris Opera Ballet School, the ambition he had to tame as a new member of American Ballet Theatre, and the reasons behind his headline-grabbing decision to be the first American to join the top rank of Bolshoi Ballet, tendered by the Artistic Director who would later be the victim of a vicious acid attack. Then, as Hallberg performed throughout the world at the peak of his abilities, he suffered a crippling ankle injury and botched surgery leading to an agonizing retreat from ballet and an honest reexamination of his entire life.

Combining his powers of observation and memory with emotional honesty and artistic insight, Hallberg has written a great ballet memoir and an intimate portrait of an artist in all his vulnerability, passion, and wisdom. “Candid and engrossing” (The Washington Post), A Body of Work is a memoir “for everyone with a heart” (DC Metro Theater Arts).

Leseprobe

A Body of Work

CHAPTER 1

Morning class was an essential daily task. Like making that pot of coffee first thing in the morning. Out of bed, half-asleep, and straight to the coffee machine. Filter. Water. Coffee grinds. On switch. Every day. Day in. Day out.

By nine thirty a.m. I would shuffle into a worn studio that was always empty and silent. The only light came from the morning sun edging in through huge windows. Outside, one floor down, the streets and noise of New York City.

At first, my body resisted the task at hand, especially when I was drained from the previous night’s performance. But the work continued the following morning, as if no exertion occurred, as if I hadn’t given to the performance every ounce of my emotional and physical energy.

I started with what I often dreaded: that first small physical movement that would call me to attention, easing me out of my slumber into another day. I would always begin with the same exercises. Done at my own pace and with the understanding that if I skipped them, I would not be set up well for later, when I would need to push my body in order to transform ballet’s absurdly difficult steps into seemingly effortless movement onstage. I began with small, basic movements, continuing on to those that are more advanced and complicated, each of them essential to achieving huge jumps and whiplash turns. People often wonder why we need daily ballet class when we are already professionals. But it is when we are performing virtuoso moves that we need those classes more than ever.

The deeper I went into the movements, the further I escaped into thought. The exercises slowly became a meditative experience. My mind would wander to last night’s show, my coming travels, the day’s rehearsals, a project I wanted to develop, a choreographer I needed to contact, emails I needed to write.

As the start of class drew near, other dancers trickled into the studio, shuffling in just as tired as I was. Everyone spoke in hushed tones. The lights would be turned on by someone who needed to feel they were officially starting class. As more dancers arrived, the volume and energy picked up. Some chatted about the show the night before, about what they did after it. Others discussed the new ballet they were learning, talking as they stretched or strengthened. A few, with headphones on, weren’t yet awake enough to discuss anything. We all wore different “uniforms.” Mine was Nike sweatpants, tights underneath, a cotton T-shirt, an insulated track jacket. Traditionalists wore nothing but tights and a T-shirt or leotard, as we all did when we were training and weren’t allowed to wear “junk”: the sweatpants, leg warmers, and baggy clothes that obscure the body and keep it from being exposed to the teacher’s critical eye. But I like junk. It’s comfortable.

Fads in dance attire come and go. In the 1970s and ’80s the more tattered and ripped your practice clothes were, the better. Maybe the wear suggested the dancer was working harder than others or was too dedicated and rehearsing too hard to take the time to buy new clothes. That has changed. I’ve gotten flak from my colleagues for having holes in my dancewear. When I was promoted to Principal Dancer a friend said, “Now you’re making Principal salary, so you can afford some better-looking clothes.”

But class is not a catwalk. The important thing is not how good the clothes look on the dancer; all that matters is what’s being danced in those clothes.

Moments before class was to begin, the teacher and accompanist would enter the studio, the former standing in the front of the room, the latter taking a seat at the grand piano.

“Are we ready?” the teacher would ask, “or do we need five more minutes?”

Always five more minutes. Compulsory for dancers to do their last stretches, yoga positions, exercises with weights. Or merely to delay the recognition that the day’s responsibilities were calling.

Grace period over, the talking ceased. We assumed our usual places at the barre. These barre spots are not free for the taking. There is, in every ballet company in the world, a pecking order. All the spots—by the piano, by the mirror, at the end, in the center—are accounted for. Some are claimed by Principal Dancers, others by members of the Corps de Ballet who have stood in the same spot for years. When outsiders come to take class with a company, they know not to claim a place at the barre until class starts. And God help the new kid who takes a much-coveted spot.

With one hand placed on the barre, we began with pliés. The most basic of movements. A dancer’s training commences at a very young age and starts with pliés at the barre. Whether you’ve danced once or a thousand times, it is the plié that begins your day.

A plié is a bending of the knees with the feet positioned in specific ways. This fundamental movement is the precursor to more advanced steps. Every turn and every jump—however high or low—starts…