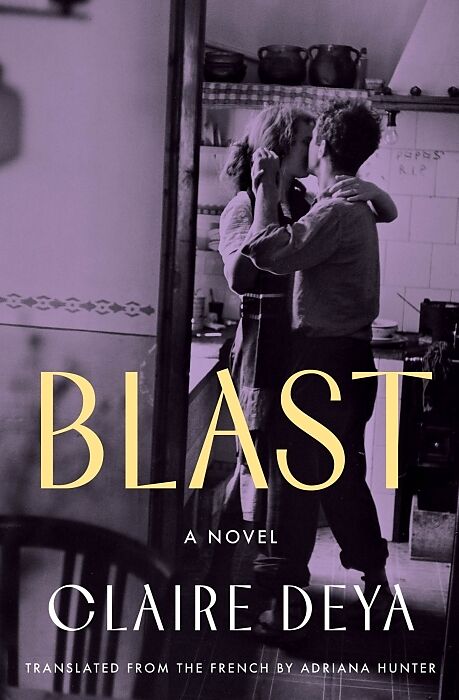

Blast

Beschreibung

An unforgettable portrait of suffering, hope, and love in post–World War II France, this cinematic debut novel uncovers the secrets of a little-known era. In spring of 1945, the war is about to end. The French coast is littered with mines the Nazis hid u...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 22.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

An unforgettable portrait of suffering, hope, and love in post–World War II France, this cinematic debut novel uncovers the secrets of a little-known era. In spring of 1945, the war is about to end. The French coast is littered with mines the Nazis hid under the sand to prevent the Allies from landing. In Hyères, on the Côte d’Azur, German prisoners are forced to clear the beaches. Alongside them, members of the Resistance and other French volunteers face the same dangerous task. With no maps of the bombs’ locations, they must be guided only by the faint trembling of the sticks they carry to detect them, in terror of being blown up. French and Germans work together, depending on each other--what grim irony--to survive, with the common goal of deactivating the mines, one by one. But this is not their only goal: Lukas plans to escape, Saskia wants to know who betrayed her family, Vincent is looking for Ariane, the woman he loves, and the Germans hold the key to her disappearance.; Historian by training and screenwriter by profession, Claire Deya brilliantly portrays the aftermath of a war that won’t truly be over until all the mines have been deactivated, showing that “people who think the fighting stops when you lay down your arms are wrong.” <Blast <captures the beginning of a postwar period in which everyone must rebuild their lives and identities, and overcome the obsessions that prevent them from healing. Revenge, mistrust, and guilt, but also solidarity, love, and forgiveness intertwine in this extraordinary novel that readers won’t be able to put down until the surprising ending.

Autorentext

Claire Deya is a French screenwriter and author. Blast is her first novel.

Adriana Hunter studied French and Drama at the University of London. She has translated more than ninety books, including Marc Petitjean’s The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris and Hervé Le Tellier’s The Anomaly and Eléctrico W, winner of the French-American Foundation’s 2013 Translation Prize in Fiction. She lives in Kent, England.

Leseprobe

If he ever did find Ariane, Vincent wouldn't dare caress her skin. His hands had reached proportions he no longer recognized. Hard, the fingers swollen, their outer surface thick, rough, and dry; they’d undergone a metamorphosis. The callused skin over them was so arid that, even when he washed them carefully and at length, they didn’t soften. There was still a constellation of black fissures burrowing deep into the bark-like covering on his palms and fingers. The soil had tattooed them with its indelible imprint by infiltrating the cracks and crevasses carved out by two winters in Germany.

Before the war, his hands used to dance when he talked. Ariane had laughed about it and imitated him. He could see her now, here, on this Riviera beach in front of him. The first time they’d come here to swim, the sun was barely up. They were still giddy from spending their first night together, and Ariane needed to get home early so no one would notice her absence. They’d walked past the beach and had been gripped by an irresistible impulse to extend their night together in the sea. Across the water, the sun bounced off the Îles d’Or, the “Golden Islands.”

He remembered the swimsuit she’d improvised by knotting a scarf around her breasts with the grace of a fearless dancer.

Her squeals as she went into the sea, the way she arched her body against his, electrified by the chill water and the rising sun . . . That salty body, desire sharpened by the sea air, the wet silk clinging to her skin. He would give anything to return to that carefree existence and dive back into the love they’d shared.

He pulled the scarf, the one he’d stolen from her, more tightly around his neck.

He’d escaped so that he could track down Ariane. She’d vanished and no one had had word of her for two years, but he was looking everywhere for her. He couldn’t believe she was dead. Impossible; she’d never do that to him. And while he’d been a prisoner, he’d received those enigmatic letters . . .

Now that the south had been liberated from the Germans, everything would be easier. They hadn’t surrendered yet, but everyone was saying they were screwed.

He had an idea about how to find Ariane. And he played up this tenuous idea to bolster his hopes. But truth be told he was just clutching at a vague intuition to save himself from going under. He was alone, and helpless, and no, the revolver he hid in his clothes like a talisman wouldn’t change anything.

While the rest of town was preparing for its first big celebration since the beginning of the war, the beach he looked down over was ravaged. Trenches and barbed-wire coils blocked access to the sea. Signs forbade entry, warned of danger. Danger of death: All along the French Riviera the beaches were mined.

Vincent could hear an amateur band rehearsing in the distance, attempting a few incursions into breezy jazz numbers. It was a beautiful day. People around him were smiling, their heads full of the promise of summer. It was almost the end of the war, and for him, most likely, the beginning of a solitary hell.

Beyond the balustrade where Vincent stood, a dozen men were spread out across the beach, advancing in a line, slowly, silently. Armed with just a bayonet, they inspected the sand with the tips of their metal pikes to detect mines buried by the Germans. Fabien took careful, focused steps, and all the men walking in the line alongside him matched their stride to his.

Fabien was not yet thirty but had naturally emerged as the group’s leader. His brotherly brand of authority, his engineering training, his commitment, from the maquis to the Resistance . . . Having blown up so many trains, he was considered the uncontested explosives specialist. The officer at the mine-clearing unit had immediately singled out this recruit to his supervisor, the Resistance fighter Raymond Aubrac.

Mine clearing was the unavoidable prerequisite to rebuilding France, but her soldiers—on the Ardennes front and then in Germany—had been relieved of this task by the interim government. Who could do the work? Demining wasn’t a profession. It was an unprecedented challenge. No one had the experience. There were so few volunteers . . . Fabien could just as easily have set off three fireworks on the deck of a ship, he would still have been elevated to the ranks of a godsend.

Rumor had it the deminers were all lost souls, godless and lawless men who’d emerged from the bowels of prisons to redeem themselves or secure an early release. Worse still, it was whispered that collaborators were trying to whitewash their dark past by melting into their ranks. Whenever Raymond Aubrac felt that anyone—at the ministry or elsewhere—was being contemptuous or patronizing about his men, he would cite Fabien as a fine example: He was the incarnation of excellence.

So much so in fact that no one could understand why he’d signed up to clear minefields. Fabien knew what people were saying about him: Having sabotaged trains, he was now sabotaging himself. The authorities put it down to some form of despair, his team thought he was hiding something, but everyone admired his courage. And you did need courage, as well as self-sacrifice, to keep risking your life rather than making the most of it.

The Ministry of Reconstruction offered assignments in blocks of three months. It looked set to take a long time: The army estimated that there was a minimum of thirteen million mines over the whole country. Thirteen million . . . So, despite war-weariness and exhaustion, men were encouraged to start a new assignment as soon as the previous one ended.

Since 1942, the Mediterranean Wa…