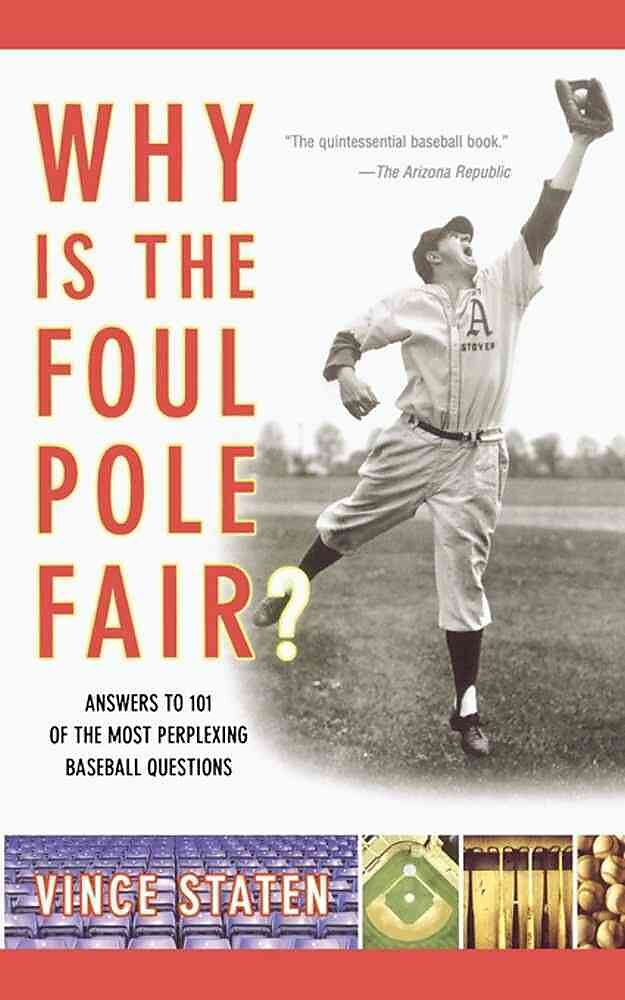

Why Is the Foul Pole Fair?

Beschreibung

Informationen zum Autor Vince Staten is the author of Ol' Diz', Unauthorized America, Real Barbecue, and Can You Trust a Tomato in January? He lives in Prospect, Kentucky. Klappentext Chicken soup for the baseball lover's soul -- the inimitable Vince Staten ta...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 26.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Informationen zum Autor Vince Staten is the author of Ol' Diz', Unauthorized America, Real Barbecue, and Can You Trust a Tomato in January? He lives in Prospect, Kentucky. Klappentext Chicken soup for the baseball lover's soul -- the inimitable Vince Staten takes you out to the ol' ballgame and answers all the baseball questions your dad hoped you wouldn't ask.

The Arizona Republic The quintessential baseball book.

Autorentext

Vince Staten is the author of Ol' Diz', Unauthorized America, Real Barbecue, and Can You Trust a Tomato in January? He lives in Prospect, Kentucky.

Klappentext

Chicken soup for the baseball lover's soul -- the inimitable Vince Staten takes you out to the ol' ballgame and answers all the baseball questions your dad hoped you wouldn't ask.

Leseprobe

Chapter One: Take Me Out to the Ball Game

I grew up in a neighborhood of boys. Tony and Mike were on one side of my house, Darnell on the other, Lance in back, next to him Michael and Donnie and Bob, then Ronald and Billy, Phil and Eddie, across the street to Tommy, up the hill to Chip and Butch.

All you needed to do on a Saturday morning was take a bat and ball to the field, then start tossing up a few and hitting them; the crack of the bat was siren call enough. Soon, there were six, eight kids, gloves in hand, ready for a pickup game.

There was always a game going in my neighborhood: football in fall, basketball in winter, and baseball the rest of the time. We didn't have a real ball field; we cobbled one together from a couple of backyards, a vacant lot, a garden, and a dog pen. My backyard was the end zone in fall, the backcourt in winter, and the infield in spring. I remember a man whom my father worked with coming by and being greatly distressed at how we neighborhood boys had worn base paths into the grass. "Those boys are killing your yard," the man said. And I remember my father's answer. "Those boys will be gone someday. That grass will grow back."

. . .

I grew up loving baseball. When I wasn't playing it, I was watching it on TV or reading about it in the Sporting News, or talking about it with my best friend Lance Harris. He and I oiled our gloves together, we taped our bats together, and, on the days we couldn't get up a game, we played catch and pepper together.

The only thing we didn't do was go to games together. There was no team in our town, big-league or otherwise. There was a Class D Rookie League franchise twenty miles away, but the big leagues were as far away as my dream of someday playing there.

At the beginning of my eleventh summer, my father announced that we wouldn't be going to the beach that year. It had been a vacation tradition for as long as I could remember. "No, not this summer," he said. Instead, we were going to a big-league baseball game. Suddenly, I couldn't breathe. This might not seem like a big deal to a city kid but, to a southern boy in the fifties, this was better than finding out you'd made Little League all-stars. See, we had no big-league clubs in the South then. The Braves were still in Milwaukee, the Astros and Rangers and Marlins and Devil Rays were all off in the future.

On our way to the distant ballpark that summer we thread through the mountains into Kentucky, then up to Cincinnati for a Reds game against my favorite team, the Giants. I'll never forget that weekend. It was the longest car ride of my life.

It was the dog days of summer when we arrived at the Queen City of the Ohio. Cincinnati is a city that's notoriously humid in the summer, but who knows from humidity when you're a kid? We unpacked in a motel on the Kentucky side of the river, then hustled over to Findlay and Western Avenue, site of the now-legendary Crosley Field.

I loved the hustle and bustle outside my first big-league park. I loved the sounds of the sidewalk barkers hawking pennants and balls and every kind of baseball trinket. I loved the crush of people scurrying to the turnstiles. And, when we finally got through the mob, a Giants pennant in my hand, and hurried up the ramp to the plaza overlooking the field, I couldn't believe my eyes. I was finally there. It was everything I had seen on television and it was in color and it was up close. Even the steel girders holding the upper deck excited me. And when we finally made our way to our seats, which were a classy green with fold-up bottoms, I was ecstatic. There, right in front of me, close enough to talk to, even touch, if I hadn't been so afraid of them, were the idols of my boyhood: Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, Jim Davenport, and Don Blasingame, and my favorite player, Orlando Cepeda.

I'll never forget my first thought: They look just like their baseball cards!

Oh, the sights and sounds that night: "Get your beer, here!" "Peeeeeeeea-nuts! Peeeeeea-nuts!" The roar when Willie Mays sent a ball over the left-field wall. The oooooh when Frank Robinson fanned.

It was a magic moment, one that I can never recapture, only recall.

Years later, when I married and had a son, my hope for him was that he grow up to love baseball. I named him Will...after my wife vetoed Orlando. Will was for two of the best players my team produced: Willie Mays and Willie McCovey. My wife thought it was for her grandfather and my grandfather. She's just finding out the truth in this book.

The winter Will was born I bought season tickets to the local Triple A club, the Louisville Redbirds, and took him to every home game his first summer. (He usually slept.)

Together, we watched the Cubs on television most afternoons and the Braves most evenings. (He preferred Thundercats cartoons.)

I signed him up for T-ball. (He hated it and spent most of his time in the outfield picking dandelions.)

For his eighth Christmas, I bought him a baseball-card album that included an assortment of cards. (He never even took the cellophane off.)

Then, came spring of his eighth year. One day after Harry Caray began bellowing "Take Me Out to the Ball Game," he went up to his room, dug out the album kit, and tore into it. Two hours later, he had all the cards neatly tucked into the polyurethane pockets. He needed more cards, he announced.

Now, he wanted to go to the Redbirds games, he wanted to get on a Little League team, he wanted to join a fantasy league. It was all happening almost too fast.

I knew what would be next: A big-league game.

I called the Reds box office. My first game had been in Cincinnati, albeit at Crosley Field; his first big-league game would be in Cincinnati, at Riverfront Stadium.

Baseball had a new fan.

Over the years, we went to games together, we operated a fantasy-league team together, we played catch in the backyard, and I pitched to him at the local field.

Then, something happened. He didn't want to go anywhere with me. He was embarrassed by my wardrobe, by my haircut, by pretty much everything about me. It's called the teen years. As he got over the embarrassment of having a father, he drifted into a new phase. Now, it wasn't that he didn't want to go to a ballgame with me, it was just that, well, Steve wanted him to play golf and Drew wanted him to bowl. And there were the calls from girls.

Now, something else has happened. His friends are all heading off to college but, because his school starts later, he's willing to hang out with his dad.

So, for the first time in five years, we are going to a big-league game together. To Cincinnati, of course. Scene of my first game, and his, too.

I just have to get us tickets.

In the beginning, it really was a game. There were no tickets; there was no need for tickets. It was just a gang of kids gathered in a field, playing a game. In some areas of this country they called it rounders, after the British game of the same name. Other places called it old cat or stool ball. It was a …