Politics and Economics of Tropical High Forest Management

Beschreibung

For the last two decades the loss of, in particular, tropical rainforest has alarmed the public in the developed parts of the world. The debate has been characterised by a lack of understand ing of the causes and effects of the process, leading to the prevaili...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 132.00

- Fester EinbandCHF 146.00

- E-Book (pdf)CHF 118.90

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

For the last two decades the loss of, in particular, tropical rainforest has alarmed the public in the developed parts of the world. The debate has been characterised by a lack of understand ing of the causes and effects of the process, leading to the prevailing reaction being unquali fied condemnation. Such attitude has even been observed among scientists, claiming suprem acy to biodiversity conservation. Many scientific analyses are available, but the basis for so ber debates and appropriate actions is still highly insufficient. Two recent international initia tives! will hopefully lead to improved knowledge of deforestation and forest degradation as they recognise the need for studies to critically investigate those issues. This book will pro vide useful input to the initiatives. In my opinion, the scientific analyses have not sufficiently promoted the understanding that the fate of tropical forests is first and foremost a concern of the governments of the countries in which the forests are situated. Tropical forests may be important to the global environment and their rich biodiversity may be a human heritage. But their main importance is their poten tial contribution to improving livelihood in the countries in question.

Klappentext

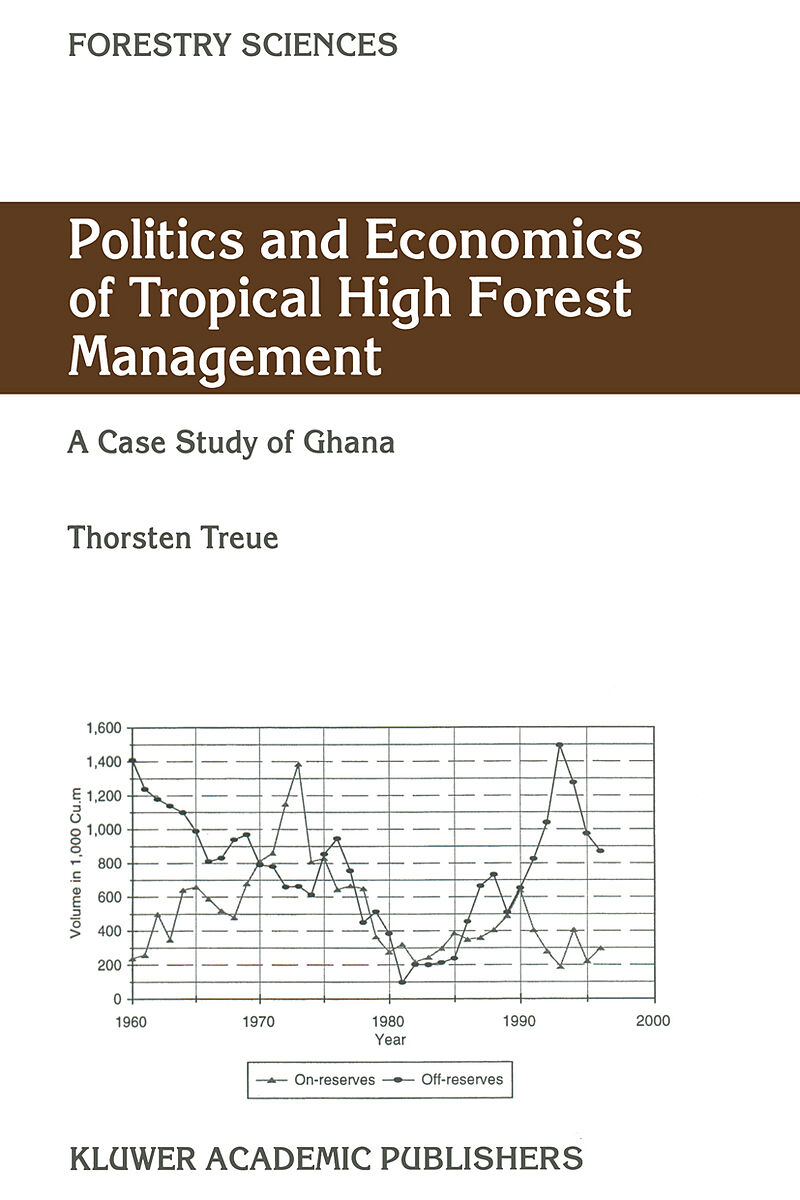

This book provides a case study into the complexity of tropical high forest in Ghana. It documents the fact that national forest inventories for a long time yielded results that were either over-optimistic about the annual allowable cut or of little use at policy level. Yet, the most important reasons for deforestation and forest degradation stem from market and legislative failures. This has resulted in major government and export revenues foregone, and the capacity of the timber industry has become far higher than the annual allowable cut from forest reserves. Trees outside forest reserves could fill the gap between the timber demand and the capacity of forest reserves. However, sustainable management of trees outside forest reserves requires clear incentives for the actual managers to do so. These managers are the rural people, who also own the land on which the trees grow. Yet, the state owns the trees. Accordingly, the challenge is for the state to replace its old exploitative attitude with a viable production-oriented approach to off-reserve timber resources.

Inhalt

1 Introduction.- 1.1 Objective of the Study.- 1.2 Methodology.- 2 Brief Introduction to Ghana's High Forest Zone.- 2.1 Forest Type and Vegetation Zones.- 2.2 Biodiversity.- 3 General Issues on Trees and Forests in the High Forest Zone.- 3.1 Functions of Trees and Forests the High Forest Zone.- 3.2 Deforestation in the High Forest Zone.- 4 The Timber Resource Base, Early Estimates.- 4.1 The Growing Stock in 1985.- 4.2 Recommendations on the Timber Harvest in 1985.- 5 National Forest Inventory (198589).- 5.1 Background of the Forest Inventory Project.- 5.2 Objectives of the Forest Inventory Project.- 5.3 Results of the FIP Static Timber Inventory.- 5.4 The FIP Dynamic Inventory.- 5.5 Other Technical Outputs of the FIP.- 5.6 Critique of the FIP.- 5.7 Policy Impact of the FIP.- 6 National Forest Inventory Continued (198997).- 6.1 Production and Protection Forest Within Forest Reserves.- 6.2 Growing Stock within Forest Reserves.- 6.3 The Sustainable Harvest Potential in Forest Reserves.- 6.4 Off-Reserve Inventory.- 7 Analysis of the Timber Harvest.- 7.1 The Log Measurement Certificate System.- 7.2 Felling Rceorded by the Forestry Department.- 7.3 This Study's Use of Available Data on Timber Harvest.- 7.4 On- and Off-Reserve Harvest.- 7.5 On-reserve Harvest and AAC.- 7.6 Off-Reserve Timber Extraction and the Resource Base.- 7.7 Policy Implications of Extraction and Resource Data.- 8 Timber Exports and the Wood Industry.- 8.1 Development in Wood Exports by Volume.- 8.2 Apparent Domestic Consumption.- 8.3 Export as the Dominant Driving Force for Timber Harvest.- 8.4 Species Composition of the Export Harvest.- 8.5 The Value of Wood Export.- 8.6 The Hidden Costs of Value Added Wood Exports.- 8.7 Structure of the Wood Industry.- 8.8 Conclusion on Wood Exports.- 9 ForestFees and Taxes.- 9.1 Overview of Forest Fees and Related Laws.- 10 The Economies of Timber Exploitation.- 10.1 Stumpage Values.- 10.2 Domestic and FOB Log Prices.- 10.3 Estimated Stumpage Values based on Log Prices.- 10.4 Estimated Stumpage Values based on FOB Lumber Prices.- 10.5 Conclusion on Derived Stumpage Values.- 10.6 Observed Actual Willingness to Pay for Standing Timber.- 10.7. Willingness to Pay Compared with Forest Taxes and Fees.- 10.8 Commercial Value of Estimated Annual Allowable Cuts.- 10.9 Revenue from Timber Off-Reserves.- 10.10 Conclusion on the Economics of Timber Exploitation.- 11 Instruments to Regulate the Timber Harvest.- 11.1 Assessment of Employed Demand-Side Measures.- 11.2 Supply-Side Measures.- 11.3 Summary Assessment of Timber Harvest Regulations.- 12 Rights to Timber and Benefits from Timber Exploitation.- 12.1 Rights to Land, Trees and Revenue On-Reserves.- 12.2. Rights to Land, Trees and Revenue Off-Reserves.- 12.3 Principles for Allocation of Rights to Standing Timber.- 12.4 Summary Assessment of Rights to Timber and Related Benefits.- 13 Forest and Timber Resources Management in the Future.- 13.1 Development of the Timber Industry.- 13.2 A Semi-Autonomous Forest Service.- 13.3 Interests of Local People.- 13.4 Management of Forest and Timber Resources.- References.- Appendices.

Produktinformationen

Weitere Produkte aus der Reihe "Forestry Sciences"

Tief- preis

- Politics and Economics of Tropical High Forest Management

- Thorsten Treue