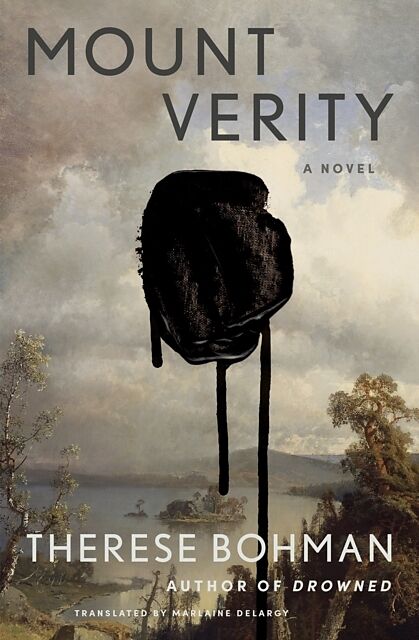

Mount Verity

Beschreibung

Tinged with Swedish lore, this enthralling coming-of-age tale explores art and guilt in the wake of a mysterious tragedy at the end of the 1980s. On the night of Easter Eve 1989, 12-year-old Hanna’s older brother Erik and some friends go to the infamous ...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 19.50

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Tinged with Swedish lore, this enthralling coming-of-age tale explores art and guilt in the wake of a mysterious tragedy at the end of the 1980s. On the night of Easter Eve 1989, 12-year-old Hanna’s older brother Erik and some friends go to the infamous Mount Verity, where there is a cave that, according to legend, was used in the witch trials in Östergötland during the 17th century. Rumor has it that whoever does not tell the truth and goes down into the cave will disappear into the mountain. Erik never comes home that night. Over the years, Hanna and her childhood friend Marcus develop an increasingly symbiotic relationship, until life takes them in different directions. He pursues an academic career, while she fails to get into art school, feeling uncertain about her path and doubting her talent. When Hanna finally becomes a successful artist, she cannot let go of what it has cost her. What justice decided that she was allowed to live while Erik vanished? What is there left to believe in when the worst has happened? And can the story of Mount Verity be more than a fable? <Mount Verity< is an atmospheric, naturalistic tale of survivor’s guilt told in prose at once dreamy, almost magical, and yet realistic and rife with slowly building suspense.

Autorentext

Therese Bohman grew up outside of Norrköping and now lives in Stockholm. Her debut novel, Drowned, received critical acclaim both in Sweden and internationally, and was selected as an Oprah Winfrey Summer Read. Her second novel, The Other Woman (Other Press, 2014), was short-listed for the Nordic Council Prize and Swedish Radio’s Fiction Prize, while her third novel, Eventide (Other Press, 2016), was short-listed for Sweden’s most prestigious literary award, the August Prize. Her fourth novel Andromeda was published by Other Press in 2025. Bohman is an arts journalist who regularly contributes to one of Sweden’s largest newspapers, Expressen.

Marlaine Delargy studied Swedish and German at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, and she taught German for almost twenty years. She has translated novels by many authors, including Kristina Ohlsson; Helene Tursten; John Ajvide Lindqvist; Therese Bohman; Theodor Kallifatides; Johan Theorin, with whom she won the Crime Writers’ Association International Dagger in 2010; and Henning Mankell, with whom she won the Crime Writers’ Association International Dagger in 2018. Marlaine has also translated nine books in Viveca Sten’s Sandhamn Murders series and two books in her Åre Murders series.

Leseprobe

PROLOGUE

On Easter Saturday 1989 I recorded almost the whole of the Top 20. I had been given a cassette player for Christmas, and even though I had been interested in music before, my interest increased when I was suddenly able to record the chart for myself. That winter I spent Saturday afternoons in front of the cassette player: I recorded, recorded over a track, recorded again. It felt sophisticated, because I thought that what I was doing wasn’t something my contemporaries did until they went to high school. Knowing which songs were in the chart made me feel grown-up.

There was plenty of drama in the spring of 1989. Debbie Gibson’s “Lost in Your Eyes” had been at number one for three Saturdays in a row, but was knocked off the top spot by Paula Abdul’s “Straight Up,” which went straight in at number one. Or “Straight up to the top,” as the radio personality Kaj Kindvall said. Genius.

On this particular Saturday I had to leave with just under half the chart still to go, because it was time for our Easter lunch. I rewound the tape back to the beginning of side B when Mom called me down, then I pressed Record and left the machine to its own devices.

I liked Easter, because it was peaceful and undemanding. Unlike Christmas and Midsummer, we celebrated at home without any visiting relatives, and without doing anything special. Four long days when everyone was free; Mom and Dad would be busy in the garden while I lay in my room reading, listening to music, and eating my Easter candy. I might go out on my bike at twilight, or watch a movie with Erik if he was home in the evening. We ate at the big dining table in the room we jokingly called the best room, which was really only used on special occasions or when we had guests. An inherited crystal chandelier hung from the ceiling, casting sparkling rainbow-colored reflections around the room when the sun’s rays caught it, but on this Saturday there was no sun. It was mild and overcast, but Mom had set the table beautifully, with lit yellow candles and napkins decorated with Easter chicks next to our plates. I don’t remember much about the meal, although I expect I thought the food was delicious. It was the same kind of perfectly ordinary celebratory food that was eaten at the same time in many Swedish homes: herring, meatballs, chipolatas, Jansson’s temptation, hard-boiled eggs cut in half and topped with a blob of mayonnaise, a prawn and a sprig of dill. I liked everything except the herring, and probably had several helpings.

After lunch Erik and I each received an Easter egg, filled with small candies and a rolled-up hundred-kronor note. It was a surprisingly large sum of money, and I immediately started fantasizing about what I could spend it on. Then I fetched a pile of Donald Duck comic books and lay down on the living-room sofa. After a little while Erik came in, grabbed one of the books, and settled down at the other end of the sofa. And so we lay there with our feet side by side, enjoying our candy. I liked those times when there was still a sense of balance and equality between us now and again, when he stopped trying to emphasize the age difference and lowered himself to my level. Like during the Christmas holiday when we did a jigsaw together, one with lots of pieces depicting the map of Sweden. And it was Erik who had taught me to use my new cassette player. One day when I was sitting drawing and listening to a tape, I suddenly felt terrified when I heard a whispering voice between two tracks. “Hanna . . . Hanna . . .” it said slowly and eerily, then Erik called out in his normal voice: “Happy name day, you old mudskipper!” That was what he used to call me when we were younger, and I thought the whole thing was so funny that I played it to my friends. I was so proud of having a big brother who not only remembered my name day but also came up with a surprise for me. Easter felt kind of heavy, somehow; we were full of food and lacking energy. It was an early Easter, the end of March, but the whole of the spring so far had been unusually warm. It was damp and mild and breezy, and as we lay there reading, the room went dark, the sky was suddenly filled with thick gray clouds.

“I hope it isn’t going to snow!” I heard Mom say. She was worried about the crocuses that were in flower all over the garden. She and Dad were still sitting at the dining table, chatting and tucking into the small cheeseboard that always appeared at special dinners. Neither Erik nor I were interested in cheese.

“This one’s cool,” Erik said, holding up the comic book. I knew exactly what he meant. It was a long adventure where Mickey Mouse and Goofy were in London, and the reader could decide how the story developed by choosing between two options, then turning to a particular page. “Is it new?”

“Kind of. It’s not one of your old ones anyway.”

“I know that.”

He was going out with his friends later, and disappeared up to his room for a while before shouting “See you later!” from the hallway. When I’d finished my book I went upstairs and rewound the tape to find out what had happened on the chart. It turned ou…