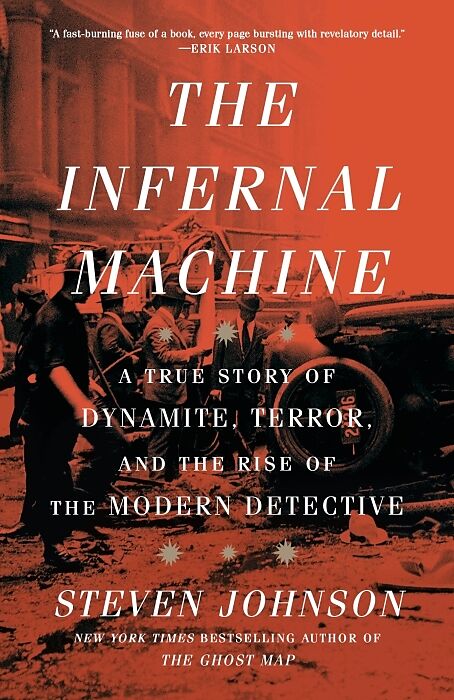

The Infernal Machine

Beschreibung

“A fast-burning fuse of a book, every page bursting with revelatory detail.”--ERIK LARSON A sweeping account of the anarchists who terrorized the streets of New York and the detective duo who transformed policing to meet the threat--a tale of fanat...Format auswählen

- Poche format BCHF 22.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

“A fast-burning fuse of a book, every page bursting with revelatory detail.”--ERIK LARSON A sweeping account of the anarchists who terrorized the streets of New York and the detective duo who transformed policing to meet the threat--a tale of fanaticism, forensic science, and dynamite from the bestselling author of A CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR • LONGLISTED FOR THE ANDREW CARNEGIE MEDAL FOR EXCELLENCE IN NONFICTION • NOMINATED FOR THE EDGAR AWARD Steven Johnson’s engrossing account of the epic struggle between the anarchist movement and the emerging surveillance state stretches around the world and between two centuries--from Alfred Nobel’s invention of dynamite and the assassination of Czar Alexander II to New York City in the shadow of World War I. April 1914. The NYPD is still largely the corrupt, low-tech organization of the Tammany Hall era. To the extent the police are stopping crime--as opposed to committing it--their role has been almost entirely defined by physical force: the brawn of the cop on the beat keeping criminals at bay with nightsticks and fists. The The new commissioner, Arthur Woods, is determined to change that, but he cannot anticipate the maelstrom of violence that will soon test his science-based approach to policing. Within weeks of his tenure, New York City is engulfed in the most concentrated terrorism campaign in the nation’s history: a five-year period of relentless bombings, many of them perpetrated by the anarchist movement led by legendary radicals Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. Coming to Woods’s aide are Inspector Joseph Faurot, a science-first detective who works closely with him in reforming the police force, and Amadeo Polignani, the young Italian undercover detective who infiltrates the notorious Bresci Circle. Johnson reveals a mostly forgotten period of political conviction, scientific discovery, assassination plots, bombings, undercover operations, and innovative sleuthing. <The Infernal Machine< is the complex pre-history of our current moment, when decentralized anarchist networks have once again taken to the streets to protest law enforcement abuses, right-wing militia groups have attacked government buildings, and surveillance is almost ubiquitous....

Autorentext

Steven Johnson is the bestselling author of thirteen books, including Enemy of All Mankind, Where Good Ideas Come From, How We Got to Now, The Ghost Map, and Extra Life. He’s the host and co-creator of the Emmy-winning PBS/BBC series How We Got to Now, the host of the podcast The TED Interview, and the author of the newsletter Adjacent Possible. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, and Marin County, California, with his wife and their three sons.

Leseprobe

Preface

July 5, 1915

Police headquarters, Centre Street, Manhattan

The bombs came in all kinds of packages.

Often they arrived in tin cans, emptied of the olive oil or soap or

preserves the cans had originally been manufactured to contain, now wedged tight with sticks of dynamite. Sometimes they were wrapped with an outer band of iron slugs, designed to maximize the destruction, conveyed to their target location in a satchel or suitcase, “accidentally” left behind in the courthouse, or the train station, or the cathedral. Many of those devices were time bombs running on clockwork mechanisms. The more inventive ones utilized a kind of hourglass device, releasing sulfuric acid into a piece of cork, the timing determined by chemistry, not mechanics: how long the acid took to eat its way through the cork, until it began dripping onto the blasting cap below. Many were swaddled in old newspaper pages. One of the most notorious bombing campaigns sent the devices through the mail, dressed up in department-store wrapping.

And sometimes the bomb was just a naked stick of dynamite, with a fuse simple enough to be lit with the strike of a match, ready to be flung into an unsuspecting crowd.

Many bombs were delivered anonymously. But others were accompanied by missives sent to a local paper, or left on a doorstep: threats, intimations of further violence, delusional rants, and more than a few manifestos. The smaller bombs—the ones detonated by a storefront, a few notches up from fireworks—were the mobster version of an “account overdue” mailing: the big stick of the extortion business. A few came from clinically insane individuals without a cause, propelled toward the terrible violence of dynamite by their own private demons. But most of the explosions that made the national news during those years were expressions, implicit or explicit, of a political worldview.

The political bombers were a diverse bunch: socialist agitators, Russian Nihilists, Irish republicans, German saboteurs. But of all the bomb throwers of the period, no group was more closely associated with the infernal machines—as the press came to call the bombs—than the anarchists. The forty-year period during which anarchism rose to prominence as one of the most important political worldviews in Europe and the United States—roughly from 1880 to 1920—happened to correspond precisely with the single most devastating stretch of political bombings in the history of the West. Indeed, the whole modern practice of terrorism—advancing a political agenda through acts of spectacular violence, often targeting civilians—began with the anarchists.

What was anarchism, really? Start with the word itself. Today the word anarchy almost exclusively carries negative connotations of chaos and disorder. But when the political movement first emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century, the word’s meaning was much more closely grounded in its etymological roots: an-, meaning no, and -archos, the Latin word for “ruler.” The anarchists believed that a world without rulers was possible. At times, they convinced themselves that such a society was inevitable; imminent, even.

The anarchists maintained that there was something fundamentally corrosive about organizing society around large, top-down organizations. Human beings, its advocates explained, oftentimes at gunpoint, had evolved in smaller, more egalitarian units, and some of the most exemplary communities of recent life—the guild-based free cities of Renaissance Europe, the farming communes of Asia, watchmaking collectives in the Jura Mountains of Switzerland—had followed a comparable template, at a slightly larger scale. These leaderless societies were the natural order of things, the default state for Homo sapiens. Taking humans out of those human-scale communities and thrusting them into vast militaries or industrial factories, building a society based on competitive struggle and authority from above, betrayed some of our deepest instincts.

At its finest moments, anarchism was a scientific argument as much as it was a political one. It had deep ties to the new science that Darwin had introduced, only it emphasized a side of natural selection that is often neglected in popular accounts: the way in which evolution selects for cooperative behavior between organisms, what Peter Kropotkin—anarchism’s most elegant advocate—called “mutual aid.”

As a theory of social organization, anarchism was equally opposed to the hierarchies of capitalism and the hierarchies of what we would now call Big Government. For this reason, it lacks an intuitive address on the conventional left-right map of contemporary politics, which partly explains why the movement can seem perplexing to us today. Whatever you might say about Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman and Peter Kropotkin—the three main anarchists in this book—they should never be mistaken for free-market libertarians. They wanted to smash the corpora…