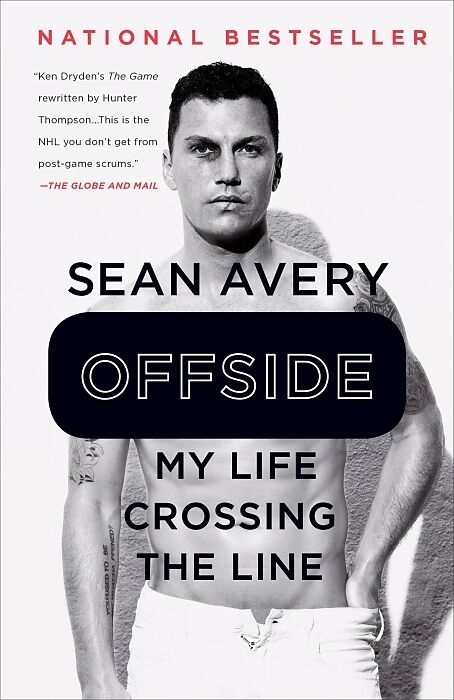

Offside

Beschreibung

Hockey's most polarizing figure takes us inside the game, shedding light not only on what goes on behind closed doors, but also what makes professional athletes tick. Sean Avery is not afraid to break the rules laid down by hockey tradition. And the most respe...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 30.30

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Hockey's most polarizing figure takes us inside the game, shedding light not only on what goes on behind closed doors, but also what makes professional athletes tick. Sean Avery is not afraid to break the rules laid down by hockey tradition. And the most respected of these is the code of silence. For the first time, a hockey player is prepared to reveal what really goes on in the NHL, in the spirit of what Ball Four did for baseball. The money, the personalities, the adultery, and the drugs--and also the little things that make up daily life in the league. Most athletes have little to say, but Sean doesn't have that problem. Yes, he tells us about the guys he's fought and the guys he's partied with, and he tells us where to find the best cougar bars in various NHL cities and what it's like to be hounded by the media when you're dating a celebrity. But Sean's job on the ice was always to get inside the heads of the guys he played against, and that insight on human nature is on full display in Offside. What makes millionaire athletes tick? What are their weaknesses? And in the end, what makes Sean Avery--once called "the most hated player in the NHL"--who he is? What is it like to make people hate you for a living? Sean Avery's misdeeds on and off the ice are well-documented, and he certainly has his detractors. But on the other hand, he has a lot of supporters, in part for things like being the first North American athlete to come out in favour of marriage equality, and in part just for being an interesting guy. Love him or hate him, he is one of the best-known players of the past few decades, and certainly one of the most colourful and outspoken. In Offside, he meets his accusers head-on, and gives them something to think about.

A Globe and Mail Bestseller

“Offside... may be described as Ken Dryden's The Game rewritten by Hunter S. Thompson.” –Globe and Mail

“[A] lively, dishy bildungsroman on skates.” –Sports Illustrated

“[Avery] pulls no punches... Love him or loathe him, Avery is unapologetically himself in his tell-all.” –TSN

“The one-of-a-kind left winger gives an unparalleled inside look at the NHL lifestyle... If you ever wanted to know what players really thought of certain coaches (Mike Babcock, Andy Murray, John Tortorella), which teammates can drive a squad nuts, or just see how the NHL sausage is made (drugs, sex, partying), Avery has the scoop... Any hockey fan will be interested in the stories he has to tell.” –The Hockey News

“Avery has happily returned the disdain in his new bridge-burning memoir. . . . [he is] the exact same disruptor as an author.” –*The Toronto Star

“He doesn’t claim to be an entirely reformed character . . . and there’s more than a hint of score-settling throughout the book. Nonetheless, Avery does want to prove he’s more than a “hate-filled wrecking ball.” –Maclean’s

“Sean Avery is the first to admit he’s made mistakes [and] it makes for colourful reading. . . . Avery throws out manhole-cover-sized brickbats.” –National Post*

"[Avery’s] voice is energetic and offbeat, and his get-real revelations about drugs, team jealousies, and the lingering damage from a violent sport will hold readers’ attention." –Publisher's Weekly

Autorentext

SEAN AVERY is a Canadian former professional hockey player. During his time with the NHL, he played left wing for the Detroit Red Wings, Los Angeles Kings, Dallas Stars, and New York Rangers. In addition to his hockey career, he has worked as a Vogue magazine intern, a model, and a restaurateur. Avery is married to model Hilary Rhoda and lives in New York.

Leseprobe

1

LAST CHANCE

I’ve wanted this since I was five years old. I’m now twenty-one, and time is running out.

Of course, looking back I realize I had lots of time, but in September 2001, all I knew was that playing the game I loved more than anything in the NHL was the only option. There was no Plan B.

My heart is pounding. I am here to earn a spot on the Detroit Red Wings of the National Hockey League. The fact that people are already talking about this as one of the best teams in history isn’t going to make things any easier. I am going to have to take a job away from someone the Red Wings actually want on the roster. And they’ve already told me in several ways that they don’t want me. This is my third crack at making the NHL—I’ve already played two seasons in the minors. Every year, a new bunch of rookies shows up, diminishing my odds. When I look around at the guys in camp, or when lying awake in bed last night, I have to ask whether I am good enough. I’m not an idiot. I know most people would say no. The Red Wings already said no.

I had been good enough once. As a kid, I played for an All-Ontario rep team. (By the way, that’s a big deal.) In my last year of junior hockey, I had twenty-eight goals and fifty-six assists for eighty-five points in fifty-five games. To put it in perspective, my fellow OHL player, Jason Spezza, had thirty-six goals and fifty assists and eighty-six points for the Windsor Spitfires in his best junior season. Spezza was chosen second overall in the first round of the 2001 NHL Entry Draft. He was beaten out by Ilya Kovalchuk, who was drafted first, and tore up the NHL for a while before walking away from $77 million and twelve years on his contract with New Jersey to play in Russia. Being drafted by the NHL doesn’t guarantee anything.

I know this too well as I wasn’t drafted at all. On draft day in 2001, part of me believed that there was at least one NHL general manager out there who would see what I could bring to a team, and another part of me believed that getting drafted was too good to be true. I wasn’t going to sit by the phone—I spent draft day at a pool party. When I came home, neither of my parents even mentioned the draft, and I didn’t ask if anyone had called. It was as if we had all moved on to the next plan of attack. I’d go to training camp as a free agent.

But still, it hurt. No one wanted me. Nearly 300 guys were taken, and not one GM wanted to use a ninth-round pick on me.

Well, I know why. The knock on me was that I was a “bad teammate.” Did this mean that I stole other players’ girlfriends? That I was an arrogant puck hog? That I put Tiger Balm in guys’ jockstraps and thought it was the funniest thing ever when they tried to extinguish the three-alarm fire burning up the family jewels?

No, none of the above. What it meant was that I played to win on every shift, and some other players don’t see the game that way. So I would let them know that they could do better. Since no one likes to be called out for dogging it, the rap landed on me that I was “bad in the room,” which in hockey-speak means you’re not one of the guys. Maybe it’s the same in other sports, but in hockey being one of the guys goes a long way. What it won’t do, though, is win you a puck battle in the corner. And it’s certainly not going to win you a fight.

So if I wasn’t going to make it as everyone’s best friend and all-round good guy, well, I’d have to make it as the opposite.

I did have one friend in Detroit, though. I knew Kris Draper from growing up in the same town that he did, Scarborough, Ontario, which is part of Toronto but so far from the city center that it’s known as “Scarberia.” In 1997–98, when Draper was then in his fifth season with the Red Wings (…