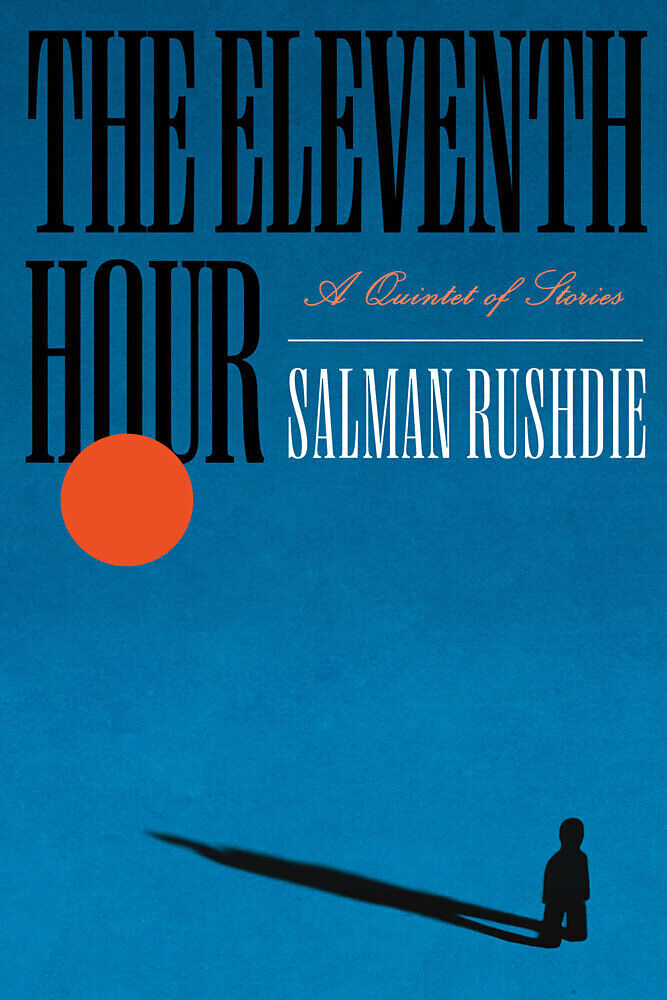

The Eleventh Hour

Beschreibung

From internationally renowned, award-winning author Salman Rushdie, an inventive collection of fiction that explores life, death, and what comes into focus at the proverbial eleventh hour of life Rushdie turns his extraordinary imagination to life’s ...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 20.30

- Fester EinbandCHF 30.30

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

From internationally renowned, award-winning author Salman Rushdie, an inventive collection of fiction that explores life, death, and what comes into focus at the proverbial eleventh hour of life

Rushdie turns his extraordinary imagination to life’s final act with a quintet of stories that span the three countries in which he has made his work—India, England, and America—and feature an unforgettable cast of characters.

“In the South” introduces a pair of quarrelsome old men—Junior and Senior—and their private tragedy at a moment of national calamity. In “The Musician of Kahani,” a musical prodigy from the Mumbai neighborhood featured in <Midnight’s Children< uses her magical gifts to wreak devastation on the wealthy family she marries into. In “Late,” the ghost of a Cambridge don enlists the help of a lonely student to enact revenge upon the tormentor of his lifetime. “Oklahoma” plunges a young writer into a web of deceit and lies as he tries to figure out whether his mentor killed himself or faked his own death. And “The Old Man in the Piazza” is a powerful parable for our times about freedom of speech.

Do we accommodate ourselves to death, or rail against it? Do we spend our “eleventh hour” in serenity or in rage? And how do we achieve fulfillment with our lives if we don’t know the end of our own stories? <The Eleventh Hour< probes life and death, legacy and identity, with wit, creativity, and keen insight.

Autorentext

Salman Rushdie is the author of fifteen novels—Luka and the Fire of Life; Grimus; Midnight’s Children (for which he won the Booker Prize and the Best of the Booker); Shame; The Satanic Verses; Haroun and the Sea of Stories; The Moor’s Last Sigh; The Ground Beneath Her Feet; Fury; Shalimar the Clown; The Enchantress of Florence; Two Years, Eight Months, and Twenty-Eight Nights; The Golden House; Quichotte (which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize); and Victory City—and one collection of short stories: East, West. He has also published six works of nonfiction—The Jaguar Smile; Imaginary Homelands; Step Across This Line; Joseph Anton; Languages of Truth; and Knife (which was a finalist for the National Book Award)—and coedited two anthologies, Mirrorwork and Best American Short Stories 2008. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Distinguished Writer in Residence at New York University. A former president of PEN America, Rushdie was knighted in 2007 for services to literature.

Klappentext

NATIONAL BESTSELLER • From internationally renowned, award-winning author Salman Rushdie, a spellbinding exploration of life, death, and what comes into focus at the proverbial eleventh hour of life

“An inventive and engrossing collection of stories which, though death-tinged, are never doom-laden. With luck this master writer has more tales to tell.”—Los Angeles Times

A NEW YORKER BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

Rushdie turns his extraordinary imagination to life’s final act with a quintet of stories that span the three countries in which he has made his work—India, England, and America—and feature an unforgettable cast of characters.

“In the South” introduces a pair of quarrelsome old men—Junior and Senior—and their private tragedy at a moment of national calamity. In “The Musician of Kahani,” a musical prodigy from the Mumbai neighborhood featured in Midnight’s Children uses her magical gifts to wreak devastation on the wealthy family she marries into. In “Late,” the ghost of a Cambridge don enlists the help of a lonely student to enact revenge upon the tormentor of his lifetime. “Oklahoma” plunges a young writer into a web of deceit and lies as he tries to figure out whether his mentor killed himself or faked his own death. And “The Old Man in the Piazza” is a powerful parable for our times about freedom of speech.

Do we accommodate ourselves to death, or rail against it? Do we spend our “eleventh hour” in serenity or in rage? And how do we achieve fulfillment with our lives if we don’t know the end of our own stories? The Eleventh Hour ponders life and death, legacy and identity with the penetrating insight and boundless imagination that have made Salman Rushdie one of the most celebrated writers of our time.

Leseprobe

The day Junior fell down began like any other day: the explosion of heat rippling the air, the trumpeting sunlight, the traffic’s tidal surges, the prayer chants in the distance, the cheap film music rising up from the floor below, the pelvic thrusts of an “item number” dancing across a neighbor’s TV; a child’s cry, a mother’s rebuke, unexplained laughter, scarlet expectorations, bicycles, the newly plaited hair of schoolgirls, the smell of strong coffee, a green wing flashing in a tree. Senior and Junior, two very old men, opened their eyes in their bedrooms on the fourth floor of a sea-green building on a leafy lane, just out of sight of Elliot’s Beach, where, that evening, the young would congregate, as they always did, to perform the rites of youth, not far from the village of the fisherfolk, who had no time for such frivolity. The poor were puritans by night and day. As for the old, they had rites of their own and did not need to wait for evening. With the sun stabbing at them through their window blinds, the two old men struggled to their feet and lurched out onto their adjacent verandas, emerging at the same moment, like characters in an ancient tale, trapped in fateful coincidences, unable to escape the consequences of chance.

Almost at once they began to speak. Their words were not new. These were ritual speeches, obeisances to the new day, offered in call-and-response format, like the rhythmic dialogues or “duels” of the virtuosi of Carnatic music during the annual December festival.

“Be thankful we are men of the south,” said Junior, stretching and yawning. “Southerners are we, in the south of our city in the south of our country in the south of our continent. God be praised. We are warm, slow, and sensual guys, not like the cold fishes of the north.”

Senior, scratching first his belly and then the back of his neck, contradicted him at once. “In the first place,” he said, “the south is a fiction, existing only because men have agreed to call it that. Suppose men had imagined the earth the other way up! We would be the northerners then. The universe does not understand up and down; neither does a dog. To a dog there is no north and south. And in the second place, you’re not that warm a character, and a woman would laugh to hear you call yourself sensual—but you are slow, that is beyond a doubt.”

This was how they were: they fought, going at each other like ancient wrestlers whose left feet were tied together at the ankles. The rope that bound them so tightly was their name. By a curious chance—which they had come to think of as “destiny,” or, as they more often called it, a “curse”—they shared a name, a long name like so many names of the south, a name neither of them cared to speak. By banishing the name, by reducing it to its initial letter, V., they made the rope invisible, which did not mean it did not exist. They echoed each other in other ways—their voices were high, they were of similarly wiry build and medium height, they were both nearsighted, and, after lifetimes of priding themselves on the qual…