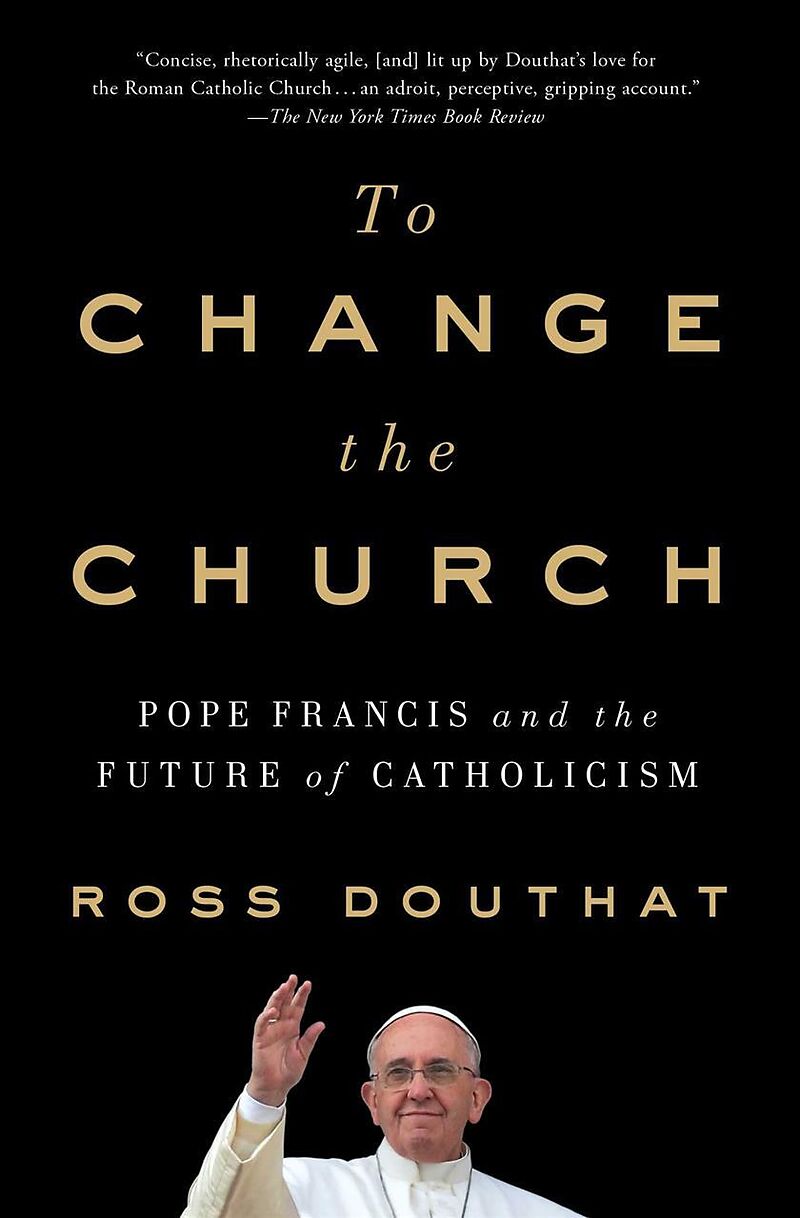

To Change the Church

Beschreibung

"Erudite and thought-provoking....weaves a gripping account of Vatican politics into a broader history of Catholic intellectual life to explain the civil war within the church....Douthat manages in a slim volume what most doorstop-size, more academic church hi...Format auswählen

- BroschiertCHF 21.90

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

"Erudite and thought-provoking....weaves a gripping account of Vatican politics into a broader history of Catholic intellectual life to explain the civil war within the church....Douthat manages in a slim volume what most doorstop-size, more academic church histories fail to achieve: He brings alive the Catholic 'thread that runs backward through time and culture, linking the experiences of believers across two thousand years.' He helps us see that Christians have wrestled repeatedly with the same questions over the past two millennia."—The Washington Post

Autorentext

Ross Douthat

Klappentext

A New York Times columnist and one of America’s leading conservative thinkers considers Pope Francis’s efforts to change the church he governs in a book that is “must reading for every Christian who cares about the fate of the West and the future of global Christianity” (Rod Dreher, author of The Benedict Option).

Born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in 1936, today Pope Francis is the 266th pope of the Roman Catholic Church. Pope Francis’s stewardship of the Church, while perceived as a revelation by many, has provoked division throughout the world. “If a conclave were to be held today,” one Roman source told The New Yorker, “Francis would be lucky to get ten votes.”

In his “concise, rhetorically agile…adroit, perceptive, gripping account (The New York Times Book Review), Ross Douthat explains why the particular debate Francis has opened—over communion for the divorced and the remarried—is so dangerous: How it cuts to the heart of the larger argument over how Christianity should respond to the sexual revolution and modernity itself, how it promises or threatens to separate the church from its own deep past, and how it divides Catholicism along geographical and cultural lines. Douthat argues that the Francis era is a crucial experiment for all of Western civilization, which is facing resurgent external enemies (from ISIS to Putin) even as it struggles with its own internal divisions, its decadence, and self-doubt. Whether Francis or his critics are right won’t just determine whether he ends up as a hero or a tragic figure for Catholics. It will determine whether he’s a hero, or a gambler who’s betraying both his church and his civilization into the hands of its enemies.

“A balanced look at the struggle for the future of Catholicism…To Change the Church is a fascinating look at the church under Pope Francis” (Kirkus Reviews). Engaging and provocative, this is “a pot-boiler of a history that examines a growing ecclesial crisis” (Washington Independent Review of Books).

Leseprobe

To Change the Church

One

THE PRISONER OF THE VATICAN

At the center of earthly Catholicism, there is one man: the Bishop of Rome, the Supreme Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ, the Patriarch of the West, the Servant of the Servants of God, the 266th (give or take an antipope) successor of Saint Peter.

This has not changed in two thousand years. There was one bishop of Rome when the church was a persecuted minority in a pagan empire; one bishop of Rome when the church was barricaded into a Frankish redoubt to fend off an ascendant Islam; one bishop of Rome when the church lost half of Europe to Protestantism and gained a New World for its missionaries; one bishop of Rome when the ancien régime crumbled and the church’s privileges began to fall away; one bishop of Rome when the twentieth century ushered in a surge of growth and persecution for Christian faith around the globe.

But all the other numbers that matter in Roman Catholicism have grown somewhat larger. When Simon Peter was crucified upside down in Nero’s Rome, there were at most thousands of Christians in the Roman Empire, and only about 120 million human beings alive in the whole world. When Martin Luther nailed his theses to the Wittenberg door, there were only 50 or 60 million Christians in all of Europe. There were probably about 200 million Catholics worldwide when Pope Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors condemned modern liberalism in 1864; there were probably about 500 million a century later when the Second Vatican Council attempted a partial reconciliation with modernity.

And now—well, to start in the red-hatted inner circle, there are more than 200 cardinals, roughly 5,100 bishops, 400,000 priests, and about 700,000 sisters in the contemporary Catholic Church.1 In the United States alone, the number of people employed by the church in some form—in schools and charities and relief organizations and the various diocesan bureaucracies—tops a million.2 Worldwide, the church dwarfs other private sector and government employers, from McDonald’s to the U.S. federal government to the People’s Liberation Army.

That’s just the church as a corporation; the church as a community of believers is vastly larger. In 2014, one sixth of the world’s human beings were baptized Catholics. Those estimated numbers? More than a billion and a quarter, or 1,253,000,000.

Catholic means “here comes everybody,” wrote James Joyce in Finnegans Wake. That was in the 1920s, when there were about 300 million Catholics, two thirds of them in Europe.

Now there are more Catholics in Latin America, more in Africa and Asia, than there were in all the Joycean world.

• • •

The papacy has never been an easy job. Thirty of the first thirty-one popes are supposed to have died as martyrs. Popes were strangled, poisoned, and possibly starved during the papacy’s tenth-century crisis. Pius VI was exiled by French Revolutionary forces; his successor, Pius VII, was exiled by Napoleon. Pius XII’s Rome was occupied by Nazis. Five popes at least have seen their city sacked—by Vandals, Ostrogoths and Visigoths, Normans and a Holy Roman Emperor.

These are extreme cases, but even the pleasure-loving pontiffs of the Renaissance found the office more punishing than they expected. “Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it,” Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici is supposed to have said upon being elected as Leo X. But his eight years as pope included a poisoning attempt, constant warfare, and the first days of the Reformation; he died at forty-five.

Huns or Visigoths no longer menace today’s popes, and their odds of being poisoned—conspiracy theories notwithstanding—are mercifully slim. But alongside the continued dangers of high office (the assassin’s bullet that struck John Paul II, the Islamic State’s dream of taking its jihad to Saint Peter’s), there are new and distinctive pressures on the papacy. The speed of mass communications, the nature of modern media, means that popes are constantly under a spotlight, their every move watched by millions or billions of eyes. Papal corruption would be an international scandal rather than a distant rumor. Papal misgovernment leads to talk of crisis in every corner of the Catholic world. Papal illness or incapacity can no longer be hidden, and aging pontiffs face a choice between essentially dying in public, like John Paul II, or taking his successor’s all-but-unprecedented step of resignation.

In an age of media exposure, the pope’s role as a public teacher is no longer confined to official letters, documents, bulls. Not just every sermon but every off-the-cuff utterance can whirl around the world before the Vatican press office has finished getting out of bed (or returned from an afternoon espresso). And theological experts are left to debate whether the magisterium of the church, that lofty-sounding word for official Catholic tea…