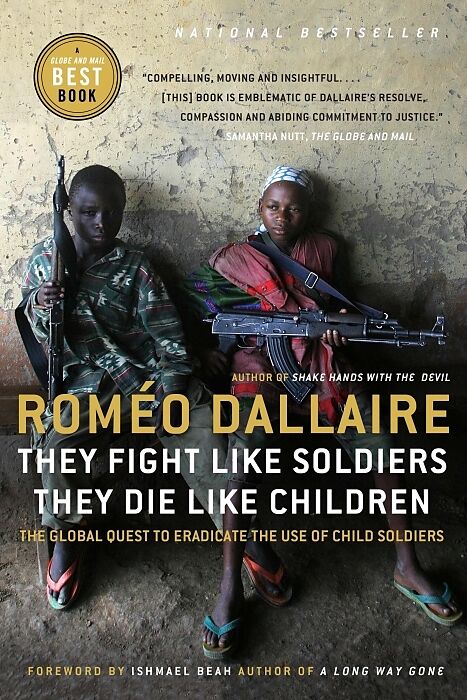

They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children

Beschreibung

"The ultimate focus of the rest of my life is to eradicate the use of child soldiers and to eliminate even the thought of the use of children as instruments of war." --Roméo Dallaire In conflicts around the world, there is an increasingly popular weapon...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 24.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

"The ultimate focus of the rest of my life is to eradicate the use of child soldiers and to eliminate even the thought of the use of children as instruments of war." --Roméo Dallaire In conflicts around the world, there is an increasingly popular weapon system that requires negligible technology, is simple to sustain, has unlimited versatility and incredible capacity for both loyalty and barbarism. In fact, there is no more complete end-to-end weapon system in the inventory of war-machines. What are these cheap, renewable, plentiful, sophisticated and expendable weapons? Children. Roméo Dallaire was first confronted with child soldiers in unnamed villages on the tops of the thousand hills of Rwanda during the genocide of 1994. The dilemma of the adult soldier who faced them is beautifully expressed in his book's title: when children are shooting at you, they are soldiers, but as soon as they are wounded or killed they are children once again. Believing that not one of us should tolerate a child being used in this fashion, Dallaire has made it his mission to end the use of child soldiers. In this book, he provides an intellectually daring and enlightening introduction to the child soldier phenomenon, as well as inspiring and concrete solutions to eradicate it.

NATIONAL BESTSELLER

A Globe and Mail Best Book

“A compelling, moving and insightful book that exposes the problem of child soldiers in all its dimensions. . . . The book is emblematic of Dallaire’s resolve, compassion and abiding commitment to justice. . . . ***Refreshingly sincere.”

— Samantha Nutt, The Globe and Mail (Best Book)

“Gripping.”

— Calgary Herald

“Discover for yourself the compassion that shines through in this book. . . . Heartbreaking and informative. . . . After all the horrors Dallaire has seen, his enthusiasm and optimism is a wonder. But it’s also infectious and refreshing.”

— The Gazette

“Painful but beautifully rendered.”

— The Vancouver Sun

“As a documentation of the changing face of modern global warfare it is a must-read.”

— Telegraph-Journal*

Autorentext

Roméo Dallaire

Leseprobe

1.

WARRIOR BOY

When I was a child, my father set out to build a cabin in the bush in the Laurentian Mountains in Quebec. The site was on a small cliff overlooking a violin-shaped lake, with virgin bush for tens of kilometres in nearly all directions around it. In the late fall and winter, the local farmers would go into the woods with their enormous horses and chains and tackles and sleighs to cut and then haul out spruce and cedar, and even the odd oak, to the provincial road where the logs would be piled sky-high until spring. I would marvel at these weather-beaten and muscle-bound farmers and their sons, who seemed to effortlessly wield enormous axes and bucksaws a hundred feet long.

My father was a staff-sergeant serving in the Canadian Army, with three children and a wife to support and no money to spare on any kind of a dream cabin. And so he brought down some of the huge trees around the site (he’d been a lumberjack before he joined the army in 1928), had them sawn into lumber at the village sawmill, and over the course of several years scrounged the rest of what he needed to complete what we not-so-affectionately dubbed the Slave Camp. Nothing really fit, be it window, plumbing or stairs. The dock regularly went astray, as the battle between man and beast (the beavers) kept the water levels in constant flux. A trip to the cabin meant steady work.

Beyond the need to constantly tweak the make-do materials of our shelter in the woods, there were other reasons for the unending labour. Dad was a huge man with a very powerful chest, heavily tattooed arms, and hands that could smother a pineapple. He was a veteran of the Second World War, and like many veterans was haunted by that experience, sometimes to the point of allowing that destructive world to invade our home life. When the brain injury we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) took hold of him, he was reliving, not remembering, the carnage he had witnessed, and perhaps caused. Sometimes he could damp down the horrors with alcohol, but often that didn’t work. The cottage turned into a therapeutic instrument that provided him with a healthier outlet for his demons. He essentially lived for the summer weekends and the two weeks of vacation each year when he could escape to the bush and work on “his” cabin.

Dad really needed to keep busy, and he expected his only son to act as his gofer. How I despised that job. Go get this, and that, and the other, for hours on end when the lake was beckoning me to swim, to fish. But no, that was play and there was no time for that when he was at the lake.

I lived for the summer days when Dad had to be in town, leaving my mother, my two sisters and me at the cabin. Although he’d pile enough chores on me to keep two men busy all week, I now had the lake to swim in without having to guiltily avoid him, and the nearby sandpits to disappear into, where I built grand fortresses and fought the greatest battles of all time on its plains using small plastic soldiers and Dinky Toy tanks. And I had the endless bush to discover.

The forest was dense and totally enveloping. I would roam at will, stopping often to idle, to listen for birdsong and animal rustling, and to dream in unadulterated freedom. I forded creeks and swamps, and climbed high cliffs to bask on large exposed rocks where the sun would soon cover me with sweat. Alone in my humanity, I shed all constraints, rules, hypocrisy, pain and sorrow, escaping from that intense childhood stress of living according to other people’s demands.

At a swamp’s edge between small lakes, birds fluttered, ducks and wild geese swam, and bugs skated on the surface of the water. There was abundance for all and no sign of calamity or friction. Life buzzed along in a sort of symphony of small sounds that soothed rather than worried or excited me.

I would daydream in the stillness, experiencing pure joy. I would tear my T-shirt into two pieces, mark it up with crayon and dirt, then string the pieces, front and back, like a loincloth. In that moment I had transformed into a Huron, an Iroquois, a Cree, a Montagnais. I was a warrior. I was a brave, skilled in the ways of the forest and free to move by instinct, by need.

The forest protected me. The canopy far above shaded me from rain and wind, and the soft forest floor cushioned my steps. I learned how to run swiftly and stealthily, without the rustle of a branch or the snap of a twig.

Among the trees I had no boundaries except what I could see and smell and touch and sense. I was alive and I was without limits. I would observe the chipmunks and marvel at the speed and adroitness of their skirmishing, neither hurting their opponent nor injuring themselves in their leaps and bounds from the forest floor to the ends of hanging limbs. I would listen to birds and wonder at so many disparate songs and screeches, and their mastery of communication. The rare deer I spotted would remain motionless to blend into the brush, but its big eyes would always give it away, for they sparkled. With a wave of its tail, it would eventually relax and move on, nibbling at vegetation as it went.

And then there were the bugs and bugs and more bugs: scurrying around old fallen dead trees and in the trunks still standing, or scuttling away from me in the mud when I lifted a mat of fallen leaves, or gliding on the surfaces and diving in the depths of the little streams. The rat-a-tat-t…