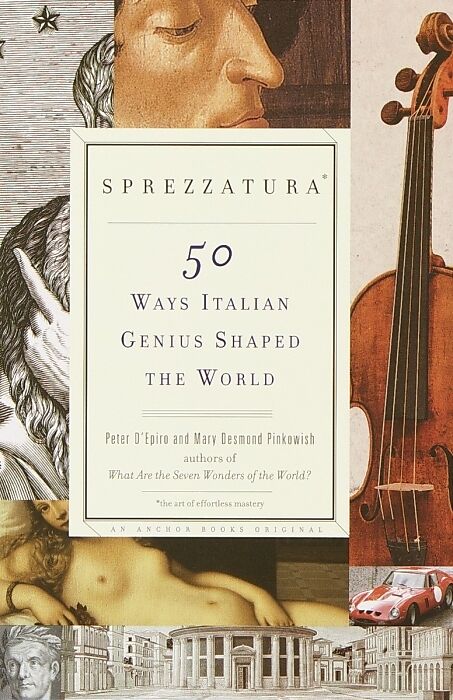

Sprezzatura

Beschreibung

Informationen zum Autor Peter D'Epiro and Mary Desmond Pinkowish are the authors of What are the Seven Wonders of the World?: And 100 Other Great Cultural Lists--Fully Explicated. Peter D'Epiro is also the author of The Book of Firsts: 150 World-Changing Peopl...Format auswählen

- Poche format BCHF 24.05

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Informationen zum Autor Peter D'Epiro and Mary Desmond Pinkowish are the authors of What are the Seven Wonders of the World?: And 100 Other Great Cultural Lists--Fully Explicated. Peter D'Epiro is also the author of The Book of Firsts: 150 World-Changing People and Events from Caesar Augustus to the Internet. He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees in English from Queens College and his M. Phil. and PH.D. in English from Yale University. He has taught English at the secondary and college levels and worked as an editor and writer for thirty years. He lives in Ridgewood, New Jersey. Mary Desmond Pinkowish is the author of numerous articles on medicine and general science for physician and lay audiences. A graduate of Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, where she studied biology and art history, she also earned a master's degree in public health from Yale University. She works for Patient Care magazine and lives in Larchmont, New York. Klappentext A witty, erudite celebration of fifty great Italian cultural achievements that have significantly influenced Western civilization from the authors of What Are the Seven Wonders of the World? "Sprezzatura, or the art of effortless mastery, was coined in 1528 by Baldassare Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier. No one has demonstrated effortless mastery throughout history quite like the Italians. From the Roman calendar and the creator of the modern orchestra (Claudio Monteverdi) to the beginnings of ballet and the creator of modern political science (Niccolò Machiavelli), Sprezzatura highlights fifty great Italian cultural achievements in a series of fifty information-packed essays in chronological order.One Rome gives the world a calendar--twice Caesar called in the best scholars and mathematicians of his time and, out of the systems he had before him, formed a new and more exact method of correcting the calendar, which the Romans use to this day, and seem to succeed better than any nation in avoiding the errors occasioned by the inequality of the solar and lunar years. --Plutarch, Lives, "Life of Julius Caesar" (c. a.d. 100) Despite current use of about forty traditional or religious calendars (such as the Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, and Chinese), it is the calendar of Julius Caesar, as slightly modified by Pope Gregory XIII, that functions as the worldwide civil norm. Yet it was a long, tortuous road that led to nearly universal adoption of this rational and elegant tool for measuring the length of the year. In its earliest known form, the Roman calendar had only 10 months and 304 days, leaving 61 days in winter uncounted and unaccounted for. This peculiar method of reckoning time was attributed to Rome's legendary founder and first king, Romulus (traditionally reigned 753-717 b.c.). In those days, January and February didn't yet exist (at least in the calendar), since Roman farmers didn't have much fieldwork to do in that dead part of the year after the last crops had been harvested and stored. After a two-month hiatus, the new year began in March with preparation of the ground for the next season's crop. Although Ovid, in his long poem on the Roman calendar, the Fasti, quips that Romulus was better at war than at astronomy, at least some of us might wish that "the year of Romulus" had prevailed, with all those discretionary days at the end. It was too good to last. The religious lawgiver Numa Pompilius, legendary second king of Rome, was credited with introducing, in about 700 b.c., the months of January and February at the end of the Roman year, lengthening it by 51 days. However, this 355-day year of what came to be called the Roman republican calendar was more probably brought to the city by the Etruscan Tarquinius Priscus (616-579 b.c.), traditionally Rome's fifth king. The ma...

Autorentext

Peter D'Epiro and Mary Desmond Pinkowish are the authors of What are the Seven Wonders of the World?: And 100 Other Great Cultural Lists--Fully Explicated. Peter D'Epiro is also the author of The Book of Firsts: 150 World-Changing People and Events from Caesar Augustus to the Internet. He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees in English from Queens College and his M. Phil. and PH.D. in English from Yale University. He has taught English at the secondary and college levels and worked as an editor and writer for thirty years. He lives in Ridgewood, New Jersey.  Mary Desmond Pinkowish is the author of numerous articles on medicine and general science for physician and lay audiences.  A graduate of Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, where she studied biology and art history, she also earned a master's degree in public health from Yale University.  She works for Patient Care magazine and lives in Larchmont, New York.

Klappentext

A witty, erudite celebration of fifty great Italian cultural achievements that have significantly influenced Western civilization from the authors of What Are the Seven Wonders of the World?

"Sprezzatura,” or the art of effortless mastery, was coined in 1528 by Baldassare Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier. No one has demonstrated effortless mastery throughout history quite like the Italians. From the Roman calendar and the creator of the modern orchestra (Claudio Monteverdi) to the beginnings of ballet and the creator of modern political science (Niccolò Machiavelli), Sprezzatura highlights fifty great Italian cultural achievements in a series of fifty information-packed essays in chronological order.

Leseprobe

One

Rome gives the world a calendar--twice

Caesar called in the best scholars and mathematicians of his time and, out of the systems he had before him, formed a new and more exact method of correcting the calendar, which the Romans use to this day, and seem to succeed better than any nation in avoiding the errors occasioned by the inequality of the solar and lunar years.

--Plutarch, Lives, "Life of Julius Caesar" (c. a.d. 100)

Despite current use of about forty traditional or religious calendars (such as the Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, and Chinese), it is the calendar of Julius Caesar, as slightly modified by Pope Gregory XIII, that functions as the worldwide civil norm. Yet it was a long, tortuous road that led to nearly universal adoption of this rational and elegant tool for measuring the length of the year.

In its earliest known form, the Roman calendar had only 10 months and 304 days, leaving 61 days in winter uncounted and unaccounted for. This peculiar method of reckoning time was attributed to Rome's legendary founder and first king, Romulus (traditionally reigned 753-717 b.c.). In those days, January and February didn't yet exist (at least in the calendar), since Roman farmers didn't have much fieldwork to do in that dead part of the year after the last crops had been harvested and stored. After a two-month hiatus, the new year began in March with preparation of the ground for the next season's crop.

Although Ovid, in his long poem on the Roman calendar, the Fasti, quips that Romulus was better at war than at astronomy, at least some of us might wish that "the year of Romulus" had prevailed, with all those discretionary days at the end. It was too good to last. The religious lawgiver Numa Pompilius, legendary second king of Rome, was credited with introducing, in about 700 b.c., the months of January and February at the end of the Roman year, lengthening it by 51 days. However, this 355-day year of what came to be called the Roman republican calendar was more probably brought to the city by the Etruscan Tarquinius Priscus (616-579 b.c.), traditionally Rome's fifth king.

The main purpose of this calendar was to ensure proper observance of forty-five religious festivals and to indicate on which days public business could or could not be conducted. Four months had 31 days, February had 28, and the rest had 29.…