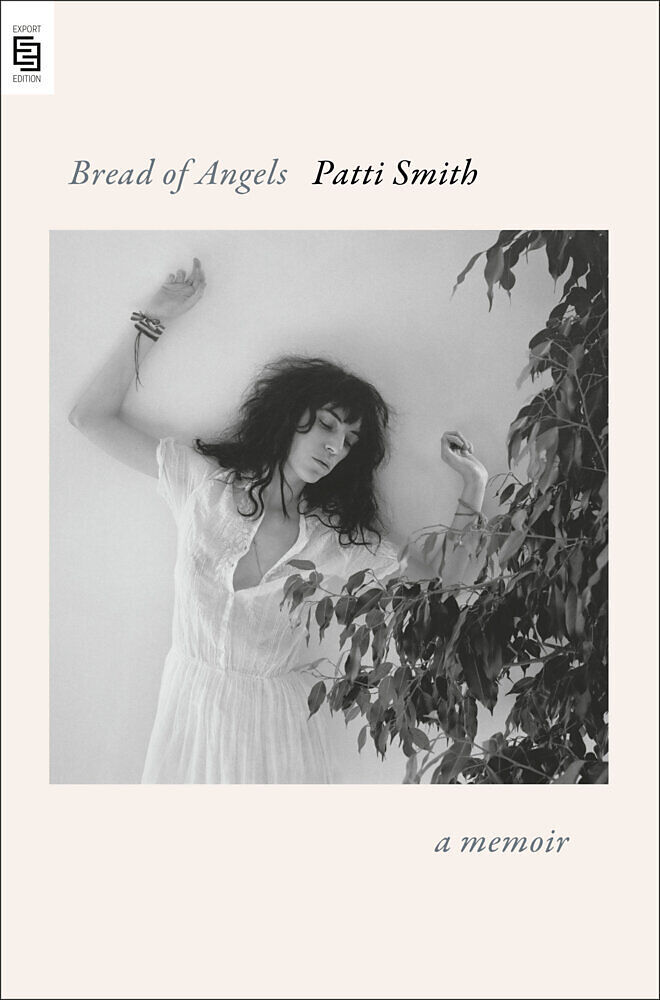

Bread of Angels

Beschreibung

An upcoming book to be published by Penguin Random House. Autorentext Patti Smith is the author of the National Book Award winner Just Kids, as well as Woolgathering, M Train, Year of the Monkey, and Collected Lyrics. Her seminal album Horses has been hailed a...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 19.00

- Fester EinbandCHF 28.45

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 30.15

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

An upcoming book to be published by Penguin Random House.

Autorentext

Patti Smith is the author of the National Book Award winner Just Kids, as well as Woolgathering, M Train, Year of the Monkey, and Collected Lyrics. Her seminal album Horses has been hailed as one of the top 100 albums of all time. Her global exhibitions include Strange Messenger, Land 250, Camera Solo, and Evidence. In 2005, the French Ministry of Culture awarded Smith the title of Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. Inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2007, Smith is also the recipient of the ASCAP Founders Award, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize, the PEN/Audible Literary Service Award, and the Legion d’honneur.

Klappentext

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • A radiant new memoir from artist and writer Patti Smith, author of the National Book Award winner Just Kids

A BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR: TIME, NPR, THE NEW YORKER

“God whispers through a crease in the wallpaper,” writes Patti Smith in this moving account of her life. A post–World War II childhood unfolds in a condemned housing complex where we enter the child’s world of the imagination. Smith, the captain of her loyal and beloved sibling army, vanquishes bullies, communes with the king of tortoises, and searches for sacred silver pennies.

The most intimate of Smith’s memoirs, Bread of Angels takes us through her teenage years where the first glimmers of art and romance take hold. Arthur Rimbaud and Bob Dylan emerge as creative role models as she begins to write poetry then lyrics, ultimately merging both into the songs of iconic recordings such as Horses, Wave, and Easter.

She leaves it all behind to marry her one true love, Fred Sonic Smith, with whom she creates a life of devotion and adventure on a canal in St. Clair Shores, Michigan. Here, she invents a room of her own, a low table, a Persian cup, inkwell and pen, entering at dawn to write. The couple spend nights in their landlocked Chris-Craft studying nautical maps and charting new adventures as they start a family.

A series of profound losses mark her life. Grief and gratitude are braided through years of caring for her children, rebuilding her life and, finally, writing again—the one constant in a life driven by artistic freedom and the power of the imagination to transform the commonplace into the magical, and pain into hope. In the final pages, we meet Smith on the road again, the vagabond who travels to commune with herself, who lives to write and writes to live.

Leseprobe

Chapter 1

The Age of Reason

The first sensation I remember is movement, my arm waves back and forth, a small endeavor that results in the toppling of Bugs Bunny from my highchair tray. My silent partner, propped there before me big as life, disappeared like a Viking ship tumbling off the edge of the world. All but a blur well beyond my reach; the earliest consequence of an action. I remember being held by my father and how different it felt from being held by my mother. He was calm; I sought his reassuring shoulder. I gravitated toward him though it was my mother who was ever present, ever dominant. Not yet one, I took my faltering first steps across the kitchen floor, then kept going. My mother was continuously challenged by her inquisitive and mobile first child who could not resist exploring, disengaging from her grip, breaking free in the park, disappearing in department stores, and spurning her affection.

She warned me of the cost of a thousand actions, but I had to see for myself and was thus bitten, stung, and exposed to all manner of insults and injuries. With little sense of the struggles surrounding me or the havoc I caused, I’d reach for the forbidden, a lit cigarette, a silver table lighter, flicking it to produce a pretty flame, sliding a tight rubber band on my wrist. A burned finger, a blue hand.

Bit by bit I piece together an ever-expanding mosaic of my pre-existence. At the end of World War II, Grant Harrison Smith, emotionally broken and plagued with malaria-induced migraines, returned to Philadelphia from active duty in New Guinea and the Philippines. He never graduated from high school, instead joining his sister and brother as the principal dancer in their tap and acrobatic trio, but the war had cut short their prospects. Beverly Williams, a young widow who had lost a son in childbirth, was working in a nightclub. They had known each other as teenagers and found comfort and familiarity in one another after the war. He was uncertain about the times ahead but believed television was the wave of the future. In 1946, he applied and was accepted to a technical school in Chicago that included a postwar incentive of a twenty dollar a week stipend. Following his plan, my parents wed in a simple civil ceremony and boarded a train to Chicago. They rented two rooms in a boardinghouse in a Polish neighborhood near Logan Square. My mother, pregnant with me, worked as a waitress for as long as she could stay on her feet.

I was due on New Year’s Eve, but arrived in the center of a huge blizzard, a day early, ruining my mother’s opportunity to receive a promotional New Year’s gift of an early freezer prototype. Instead, she continued using an old-fashioned ice chest, waiting each week for the iceman in his horse cart to deliver a large block of ice.

Within the pages of My First Seven Years, my oversized faded pink baby book filled with lists of illnesses, birthdays, and notations of my progress, my mother inscribed a poem entitled Patti. One could sense her joy giving birth to a little girl, though a sickly one with severe bronchial distress. My father said I was born coughing. He bundled me up, and together they departed the hospital in a swirl of snow. My mother said that he saved my life, holding me for hours over a steaming stand-up washtub. But I knew nothing of these things, neither the hopes of my father nor the labors of my mother, soon pregnant with another child.

My sister Linda was born thirteen months after me, during yet another Chicago blizzard. At two, I couldn’t pronounce Linda, so I called her Dinny, and for some time that name remained. I can picture my mother with her dark wavy hair and ever-present cigarette, with me toddling about, another in a carriage, and secretly carrying a third beneath an oversized Chesterfield coat. When she could no longer hide the pregnancy, our landlord forced us to relocate. With a third child on the way, my father was obliged to leave behind his vision of stepping into the fast-evolving technical world of television and find full-time work.

My mother listed all our addresses in my baby book. In the first four years of my life, we relocated eleven times, from rooming houses to furnished flats. We traveled by train to Philadelphia, stopping for a brief, unwelcomed stay with my father’s beautiful but mean-spirited sister, Gloria. I can picture my grandmother Jessie’s spinet, a small upright piano, and my aunt whacking me for attempting to play.

That winter we moved from Gloria’s to nearby Hamilton Street. My father found a job in a union factory, working the night shift; my mother continued to waitress. On Christmas Eve after a long day waiting tables, before she boarded the crowded bus home, my mother bought two large lollipops and two small hand-painted wooden penguins for our stockings, all she could afford. When she got off a strap dangled; someone had cut it and made off with her shoulder bag. She would recount the story over the years, still stricken that we had no presents for Christmas that year. Since then, I have found it impossible to pass up little penguins in flea markets or dime stores, as if to fill the vast ice field left in her sad sturdy heart.

Our new baby brother was born in June …