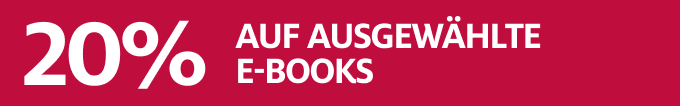

Kalaripayat

Beschreibung

The Martial Arts Tradition of India. ". . . the work [Kalaripayat] is a useful and detailed introduction to kalaripayat within its larger social, cultural, and religious context. As the author rightfully states, kalaripayat deserves a place alongside the other...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 20.00

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

The Martial Arts Tradition of India.

". . . the work [Kalaripayat] is a useful and detailed introduction to kalaripayat within its larger social, cultural, and religious context. As the author rightfully states, kalaripayat deserves a place alongside the other, more well-known Asian martial arts traditions. . . [Kalaripayat] will bring kalaripayat to the attention of a wider audience and inspire further research and publication on this art."

Autorentext

Patrick Denaud is a former war correspondent for CBS News and a documentary filmmaker. He lives in France.

Klappentext

MARTIAL ARTS / INDIA "In order to grasp the common essence of the martial arts, or the original unity of mankind for that matter, it is necessary to understand the truth of history. Patrick Denaud's Kalaripayat reveals many important pieces of this enigmatic and fascinating puzzle. It is an important book for serious students of all martial arts." --William Gleason, author of Aikido and Words of Power and The Spiritual Foundations of Aikido Originating in the southern Indian province of Kerala, kalaripayat is the most ancient of the Eastern martial arts. Yet today it has been practically forgotten. Former CBS war correspondent Patrick Denaud looks at this neglected tradition, whose history spans millennia, from the time it was transmitted by the god Vishnu to the sage Parasurama and his twenty-one disciples, the original Gurukkals, to its present-day practice. More than an art of combat, kalaripayat is a way of life and a spiritual discipline. Its martial techniques are designed to create states propitious for deep meditation. Long the jealously guarded art of the Nair warriors of southern India, kalaripayat was banned by the British East India Company in 1793 and was long believed by outside observers to be extinct. Several Gurukkals continued a clandestine practice and secretly trained the students who would transmit the teachings to today's keepers of the art, such as Gurukkal P. S. Balachandran. Like other spiritual disciplines, kalaripayat draws from the science of breath. Focused, silent breathing creates highly concentrated trance states and helps control the inner circulation of vital energy. The practitioner learns not only how to be a capable fighter with or without weapons but also an accomplished healer. The emphasis of this practice on circulating energy throughout the body is not only of interest to martial arts practitioners but also to all those interested in the harmonious development of the self. PATRICK DENAUD is a former war correspondent for CBS News and a documentary filmmaker. He lives in France.

Zusammenfassung

The first book in English on the Indian martial art that was the precursor to the Chinese and Japanese traditions

• A rigorous martial arts practice that also promotes harmonious self-development

• Provides practices for controlling the circulation of energy and vital forces throughout the body

Originating in the southern Indian province of Kerala, kalaripayat is the most ancient of the Eastern martial arts. Yet today it has been practically forgotten. Former CBS war correspondent Patrick Denaud looks at this neglected tradition, whose history spans millennia, from the time it was transmitted by the god Vishnu to the sage Parasurama and his twenty-one disciples, the original Gurukkals, to its present-day practice.

More than an art of combat, kalaripayat is a way of life and a spiritual discipline. Its martial techniques are designed to create states propitious for deep meditation. Long the jealously guarded art of the Nair warriors of southern India, kalaripayat was banned by the British East India Company in 1793 and was long believed by outside observers to be extinct. Several Gurukkals continued a clandestine practice and secretly trained the students who would transmit the teachings to today’s keepers of the art, such as Gurukkal Pratap S. Balachandrian.

Like other spiritual disciplines, kalaripayat draws from the science of breath. Focused, silent breathing creates highly concentrated trance states and helps control the inner circulation of vital energy. The practitioner learns not only how to be a capable fighter with or without weapons but also an accomplished healer. The emphasis of this practice on circulating energy throughout the body is not only of interest to martial arts practitioners but also to all those interested in the harmonious development of the self.

Leseprobe

**Chapter 6

Engagement

Le Rencontre

Madras, 1994

*

My guide wants me to visit an old Kalaripayat master who is also a master of yoga breathing and meditation. “An astonishing person, a sage,” he tells me. An appointment is arranged for me.

The house is at the end of a dusty street teeming with children as they always are in India--a street with indescribable odors, bitter, unsavory

yet suddenly rather sensual. On one side of the road, shacks and their beggars line the route.

I push open a heavy door and an old woman comes toward me, bowing repeatedly, offering words of welcome that my guide translates for me. She leads me through a dark corridor to the living room that looks out on a garden burgeoning with luxurious vegetation including jackfruit trees and bougainvillea.

A door opens slowly. The old master, aristocratic, with haughty bearing, who is called Pratap, appears and leads us to a large, empty room furnished only with a carpet.

“Have a seat,” he says, indicating the carpet.

With a supple movement, he is quickly seated and there we are both crouched down in the hot, muggy atmosphere of the room. After offering a few polite words, I explain the reason for my visit, my interest in Kalaripayat and my research on the martial art and its different techniques.

He looks at me with a slight smile, his eyes twinkling. In spite of his advanced age, his look is amazingly lively. His body seems lithe and muscular.

“May I help you?”

He speaks perfect English, a result of the British occupation. On a kind of wooden stand where incense is burning, filling the room with its penetrating scent, palm leaf manuscripts arouse my curiosity. The master hands one to me and explains, “I write these at night. They are texts that summarize my experience with our art. Some young people who like to call themselves my disciples often come here to read them.”

After a few minutes, the old woman returns with a pot of boiling tea, bananas, mangos, and coconut.

He shows me other documents, several centuries old he tells me, in which we see animals in combat (lions, monkeys, serpents). These documents are handed down from generation to generation. Written by hand on palm leaves and illustrated with finely engraved diagrams, these documents deal with astrology, medical science, pressure points, and the art of combat. They are written in the Malayalam language (a Dravidian language of south India) and are anonymous: Parappa Padu Varman Pandirndum, Pankanam Todu Maram Thonutiaarun*.

Pratap then tells me about the origins of his art and how the great masters observed the combat techniques of animals:

“Kalaripayat proceeds from two great principles: the mind is in charge in the body and one’s opponent is vanquished by turning his own force back on him. The swallow swoops down to peck, the bear grabs, the serpent undulates, the crane spreads his wings and pecks with his beak. The masters of former times, having withdrawn to the solitude of the mountains to live in harmony with nature and to meditate, studied and observed the movements of various animals, and from these creatures they learned their main defense and attack positions.”

I steer the conversation toward meditation and the breathing practices that the masters deem so important and that they so…