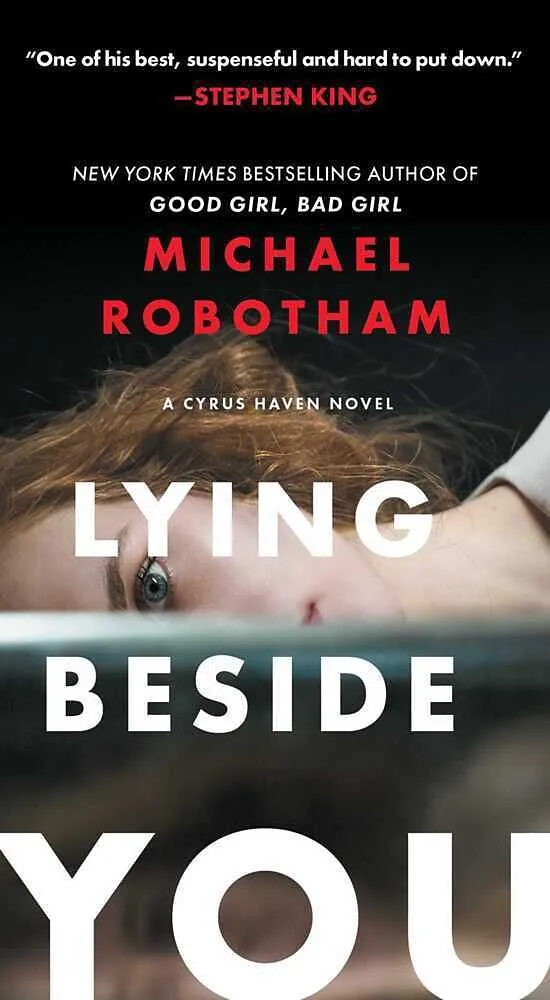

Lying Beside You

Beschreibung

Cyrus Haven and Evie Cormac return in this "expertly paced and psychologically acute" (Kirkus Reviews, starred review) thriller from Michael Robotham that's "one of his best, suspenseful and hard to put down" (Stephen King). Twenty yea...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 13.00

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Cyrus Haven and Evie Cormac return in this "expertly paced and psychologically acute" (Kirkus Reviews, starred review) thriller from Michael Robotham that's "one of his best, suspenseful and hard to put down" (Stephen King).

Twenty years ago, Cyrus Haven survived a family massacre. The killer? His brother Elias.

Now Elias is applying for release from a secure psychiatric hospital-and Cyrus is expected to forgive and welcome him home. In this "brilliant novel" (The Globe and Mail, Toronto), Elias is returning to a very different world. Cyrus is now a successful psychologist, working with the police, sharing his house with Evie Cormac, a damaged and gifted teenager who can tell when someone is lying.

When a man is murdered and his daughter Maya Kirk disappears, Cyrus is called in to profile the killer and help piece together Maya's last hours. Soon, a second victim is taken, and Evie is the only person who glimpsed the man behind the wheel. But there's a problem. Only two people believe her. One is Cyrus.

The other is the killer.**

Autorentext

Michael Robotham is a former investigative journalist whose bestselling psychological thrillers have been translated into twenty-five languages. He has twice won a Ned Kelly Award for Australia's best crime novel, for Lost in 2005 and Shatter in 2008. His recent novels include When She Was Good, winner of the UK's Ian Fleming Steel Dagger Award for best thriller; The Secrets She Keeps; Good Girl, Bad Girl; When You Are Mine; Lying Beside You; Storm Child; and The White Crow. After living and writing all over the world, Robotham settled his family in Sydney, Australia.

Leseprobe

Chapter 1: Cyrus 1 Cyrus

If I could tell you one thing about my brother, it would be this: two days after his nineteenth birthday, he killed our parents and our twin sisters because he heard voices in his head. As defining events go, nothing else comes close for Elias, or for me.

I have often tried to imagine what went through his mind on that cool autumn evening, when our neighbors began closing their curtains to the coming night and the streetlights shone with misty yellow halos. What did the voices say? What possible words could have made him do the things he did?

I have tortured myself with what-ifs and maybes. What if I hadn't stopped to buy hot chips on my way home from football practice? What if I hadn't propped my bike outside Ailsa Piper's house, hoping to glimpse her in her garden or coming home from her netball practice? What if I had pedaled faster and arrived home sooner? Could I have stopped him, or would I be dead too?

I am the boy who survived, the one who hid in the garden shed, crouching among the tools, smelling the kerosene and paint fumes and grass clippings, while sirens echoed through the streets of Nottingham.

In my nightmares, I always wake as I step into the kitchen, wearing muddy football socks. My mother is lying on the floor amid the frozen peas, which had spilled across the white tiles. Chicken stock is bubbling on the stove and her famous paella has begun to stick in the heavy-based pan.

I miss my mum the most. I feel guilty about playing favorites, but nobody is around to criticize my choices, except for Elias, and he doesn't get to choose. Ever.

Dad died in the sitting room, crouching in front of the DVD player because one of the twins had managed to get a disk stuck in the machine. He raised one hand to protect himself and lost two fingers and a thumb, before the knife severed his spine.

Upstairs, in the bedroom, Esme and April were doing their homework or playing games. Esme, older by twenty minutes, and therefore bossier, was usually the first to do everything, but it was April, dressed in a unicorn onesie, who ran towards the knife, trying to protect her sister. Esme had to be dragged from beneath her bed and died with a rug bunched beneath her body and a ukulele in her hand.

Many of these details have the power to close my throat or wake me screaming, but as snapshots they are fading. My memories aren't as vivid as they once were. The colors. The smells. The sounds. The fear.

For example, I can no longer remember what color dress my mother was wearing, or which of the twins had her hair in braids that week. (Esme and April took it in turns to help their teachers differentiate between them, or maybe to confuse them further.)

And I can't remember if Dad had opened a bottle of home brew-a six o'clock ritual in our household, when he uncapped his latest batch with a brass Winston Churchill bottle opener. With great ceremony, he would pour the "amber nectar" into a pint glass, holding it up to the light to study the color and opacity. And when he drank, he would swish that first sip around in his mouth, sucking in air, like a wine connoisseur, saying things like, "Bit malty... a little cloudy... a tad early... half-decent... buttery... quenching... perfect in another week."

It is these small details that elude me. I can't remember if I knocked the mud off my football boots, or if I chained up my bike, or if I closed the side gate. I can remember stopping to wash the salt from my hands and to gulp down water, because Mum hated me spoiling my appetite by eating junk food so close to dinnertime. In the same breath, she'd complain about me having "hollow legs" and "eating her out of house and