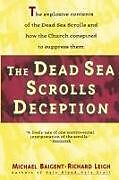

Dead Sea Scrolls Deception

Beschreibung

Chicago Tribune Not for the theologically faint of heart. Autorentext Michael Baigent graduated from Canterbury University, Christchurch, New Zealand, Richard Leigh followed his degree from Tufts University with postgraduate studies at the University of Chicag...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 25.50

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Chicago Tribune Not for the theologically faint of heart.

Autorentext

Michael Baigent graduated from Canterbury University, Christchurch, New Zealand, Richard Leigh followed his degree from Tufts University with postgraduate studies at the University of Chicago and the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Together the authors have also written Holy Blood, Holy Grail; The Messianic Legacy; and The Temple and the Lodge. Both writers live in England.

Klappentext

Through a careful study of the scrolls, historical analysis, and interviews w ith scholars, the authors establish a view of Christianity that challenges the Church's adamantly defended "facts". Photographs.

Zusammenfassung

The oldest Biblical manuscripts in existence, the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in caves near Jerusalem in 1947, only to be kept a tightly held secret for nearly fifty more years, until the Huntington Library unleashed a storm of controversy in 1991 by releasing copies of the Scrolls. In this gripping investigation authors Baigent and Leigh set out to discover how a small coterie of orthodox biblical scholars gained control over the Scrolls, allowing access to no outsiders and issuing a strict "consensus" interpretation. The authors' questions begin in Israel, then lead them to the corridors of the Vatican and into the offices of the Inquisition. With the help of independent scholars, historical research, and careful analysis of available texts, the authors reveal what was at stake for these orthodox guardians: The Scrolls present startling insights into early Christianity -- insights that challenge the Church's version of the "facts." More than just a dramatic exposé of the intrigues surrounding these priceless documents, The Dead Sea Scrolls Deception presents nothing less than a new, highly significant perspective on Christianity.

Leseprobe

Chapter 1

The Discovery of the Scrolls

East of Jerusalem, a long road slopes gradually down between barren hills sprinkled with occasional Bedouin camps. It sinks 3800 feet, to a depth of 1300 feet below sea-level, and then emerges to give a panoramic vista of the Jordan Valley. Away to the left, one can discern Jericho. In the haze ahead lie Jordan itself and, as though seen in a mirage, the mountains of Moab. To the right lies the northern shore of the Dead Sea. The skin of water, and the yellow cliffs rising 1200 feet or more which line this (the Israeli) side of it, conduce to awe -- and to acute discomfort. The air here, so far below sea-level, is not just hot, but palpably so, with a thickness to it, a pressure, almost a weight.

The beauty, the majesty and the silence of the place are spell-binding. So, too, is the sense of antiquity the landscape conveys -- the sense of a world older than most Western visitors are likely to have experienced. It is therefore all the more shocking when the 20th century intrudes with a roar that seems to rupture the sky -- a tight formation of Israeli F-16s or Mirages swooping low over the water, the pilots clearly discernible in their cockpits. Afterburners blasting, the jets surge almost vertically upwards into invisibility. One waits, numbed. Seconds later, the entire structure of cliffs judders to the receding sonic booms. Only then does one remember that this place exists, technically, in a state of permanent war -- that this side of the Dead Sea has never, during the last forty-odd years, made peace with the other. But then again, the soil here has witnessed incessant conflict since the very beginning of recorded history. Too many gods, it seems, have clashed here, demanding blood sacrifice from their adherents.

The ruins of Qumran (or, to be more accurate, Khirbet Qumran) appear to the right, just as the road reaches the cliffs overlooking the Dead Sea. Thereafter, the road bends to follow the cliffs southwards, along the shore of the water, towards the site of the fortress of Masada, thirty-three miles away. Qumran stands on a white terrace of marl, a hundred feet or so above the road, slightly more than a mile and a quarter from the Dead Sea. The ruins themselves are not very prepossessing. One is first struck by a tower, two floors of which remain intact, with walls three feet thick -- obviously built initially with defence in mind. Adjacent to the tower are a number of cisterns, large and small, connected by a complicated network of water channels. Some may have been used for ritual bathing. Most, however, if not all, would have been used to store the water the Qumran community needed to survive here in the desert. Between the ruins and the Dead Sea, on the lower levels of the marl terrace, lies an immense cemetery of some 1200 graves. Each is marked by a long mound of stones aligned -- contrary to both Judaic and Muslim practice -- north-south.

Even today, Qumran feels remote, though several hundred people live in a nearby kibbutz and the place can be reached quickly and easily by a modern road running to Jerusalem -- a drive of some twenty miles and forty minutes. Day and night, huge articulated lorries thunder along the road, which links Eilat in the extreme south of Israel with Tiberius in the north. Tourist buses stop regularly, disgorging sweating Western Europeans and Americans, who are guided briefly around the ruins, then to an air-conditioned bookshop and restaurant for coffee and cakes. There are, of course, numerous military vehicles. But one also sees private cars, both Israeli and Arab, with their different coloured number-plates. One even sees the occasional 'boy racer' in a loud, badly built Detroit monster, whose speed appears limited only by the width of the road.

The Israeli Army is, needless to say, constantly in sight. This, after all, is the West Bank, and the Jordanians are only a few miles away, across the Dead Sea. Patrols run day and night, cruising at five miles per hour, scrutinising everything -- small lorries, usually, with three heavy machine-guns on the back, soldiers upright behind them. These patrols will stop to check the cars and ascertain the precise whereabouts of anyone exploring the area, or excavating on the cliffs or in the caves. The visitor quickly learns to wave, to make sure the troops see him and acknowledge his presence. It is dangerous to come upon them too suddenly, or to act in any fashion that might strike them as furtive or suspicious.

The kibbutz -- Kibbutz Kalia -- is a ten-minute walk from Qumran, up a short road from the ruins. There are two small schools for the local children, a large communal refectory and housing units resembling motels for overnight tourists. But this is still a military zone. The kibbutz is surrounded by barbed wire and locked at night. An armed patrol is always on duty, and there are numerous air-raid shelters deep underground. These double for other purposes as well. One, for example, is used as a lecture hall, another as a bar, a third as a discothèque. But the wastes beyond the perimeter remain untouched by any such modernity. Here the Bedouin still shepherd their camels and their goats, seemingly timeless figures linking the present with the past.

In 1947, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, Qumran was very different. At that time the area was part of the British mandate of Palestine. To the east lay what was then the kingdom of Transjordan. The road that runs south along the shore of the Dead Sea did not exist, extending only to the Dead Sea's north-western quarter, a few miles from Jericho. Around and beyond it there were only rough tracks, one of which followed the course of an ancient Roman road. This route had long been in total disrepair. Qumran was thus rather more difficult to reach than it is today. The sole human presence in the vicinity would have been the Bedouin, herding their camels and goats during the winter and spring, when the desert, perhaps surprisingl…