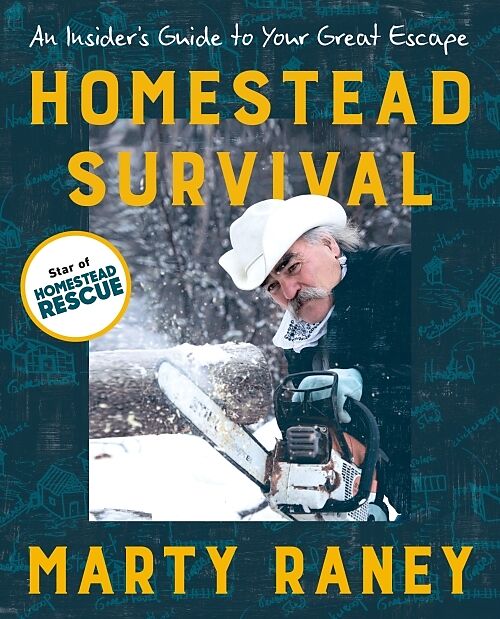

Homestead Survival

Beschreibung

Autorentext Marty Raney is the host and producer of Discovery's Homestead Rescue and Raney Ranch. A former Denali mountain guide and life-long Alaskan survivalist, Marty has made his life off the grid, and in the mountains, in one of the most extreme environme...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 32.40

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Autorentext

Marty Raney is the host and producer of Discovery's Homestead Rescue and Raney Ranch. A former Denali mountain guide and life-long Alaskan survivalist, Marty has made his life off the grid, and in the mountains, in one of the most extreme environments on the planet. He was featured on every season of National Geographic Channel’s Ultimate Survival Alaska. He lives off the grid with his family in Southcentral Alaska.

Klappentext

"A practical guide to self-sufficient and sustainable living from the star of Homestead Rescue. Do you wish for a more resilient, sustainable, and empowered way of providing for your family in uncertain times? Are you worried about unreliable power grids, uncertain water supplies, or overly complex food chains? Veteran homesteader and star of the Discovery Channel's Homestead Rescue Marty Raney shares a big-picture vision of how ordinary families can become radically resilient homesteaders: powering, feeding, and caring for themselves through their own efforts, and on their own land"--

Leseprobe

-  One  -

The Homesteader Mentality

The desire to live freely, deliberately, and simply under

the banner of homesteading is alive and well

As I travel from homestead to homestead, the plane's window becomes a wide lens into the past, focusing on the vast North American landscape below. And, at thirty-five thousand feet, I watch a historical documentary unfold in geographic

increments: cities surrounded by suburbs, suburbs blended away to occasional rural villages, and then, there they are. The indelible survey section gridlines-now visible as roads or fence lines-carving out the homesteads and farmlands that can be traced to the Civil Warera Homestead Act of 1862, an act that allowed any American, whether rich or poor, to receive a 160-acre plot of land for a filing fee of eighteen dollars.

Abraham Lincoln believed that the role of government should be "to elevate the condition of men, to lift artificial burdens from all shoulders and to give everyone an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life." And for a period of time lasting well over a century, Americans were able to claim their lot in life. It wasn't a perfect system, and looking back we have to acknowledge the bad as well as the good: Although newly freed Black Americans were technically able to claim land this way, few successfully did. Indigenous tribes were forcibly removed from their homelands, causing generational despair and great loss of life. People abused the system too, with wealthy homesteaders figuring out ways to claim multiple homesteads in good locations. Lincoln's actions reshaped this country, and by the close of the act, over four million homestead claims were filed in more than thirty states, with the last being claimed by a man named Ken Deardorff, along the Stony River in Alaska in 1976.

Those dreamers carved a legacy of self-sufficient homesteads, farms, ranches, and orchards, all the way to the Pacific Ocean and then north to Alaska. From my window seat, I can easily see the fenced, bordered sections of land, each section representing 640 acres, or one square mile. The patchwork of squared farmland is a timeless reminder of where we came from, and where our food still comes from.

Two hundred years later, however, the migration has reversed, with young people going from the farm, to the factory, to the office. Many of the original "square mile" farms have been broken down to smaller tracts of 320, 160, 80, or 40 acres, and so on. The first subdivision was most likely built on an old homestead, since a two-acre homesite is worth five times more than a two-acre potato field.

The transition of family farms to factories was exacerbated as World War II came and went. Interestingly, the subdivisions we see everywhere were actually "invented" during that era-an amazing, novel idea at the time. The original two-, four-, six-, and eightplexes evolved into apartment and condominium housing en masse. Homesteads were surveyed, and developers greedily carved them into one-acre lots, and boom: We planted houses in the fields, resulting in the first fruits of shiny, sprawling suburbia. And, just like the rows of corn planted by the farmer as close together as possible to yield maximum profit, the concrete and wood bumper crop planted by developers has left us all living as close as we possibly can to each other-for the same reason: profit.

The overcrowding serves as a petri dish for pandemics, unrest, anxiety, and a culture lacking the fundamental core to keep it all together under a stressful, straining, burdensome load. As the original farms dissolved, so did the original homesteader's legacy of knowledge and experience: Many of their descendants have forgotten the skill sets needed to thrive self-sufficiently. Today 330 million Americans are completely dependent on the grid, the grocery store, and the gas station to survive, day by day. Take one of those away from the city or the suburb, for just one day? Chaos. Panic. Twenty-four hours of disruption could put those crowded, grid-dependent masses in real danger.

Salt and Cabbage

That ancestral memory of homesteading is closer to the surface than you might realize. Think of sauerkraut: It's salt, cabbage, and a little physical labor. Take any root vegetable, immerse it in a brine, and leave it in your cellar or pantry; you are now a little more prepared for a food shortage than you were ten minutes ago. That combination of vegetable, mineral, and fermentation is so simple you don't need a recipe, so commonplace that every culture in the world practices some variation of it, and so essential to early homesteading that most early root cellars would have been lined with jars or crocks of it. The skills a successful homesteader needs are never more than a generation or two lost in the past. What is harder to recover is that spirit of homesteading, that willingness to take a chance and work collectively toward a difficult and labor-intensive goal. My family has succeeded at homesteading because we are willing to work hard and because we share a common vision

of what a well-lived life looks like. So when you begin to consider a homesteading life, ask yourself, "What is our family vision? Do we have what it takes to stand together, united, come what may?"

Putting the Home into Homestead

Homesteading is a group activity. Successful homesteads have a cohesive, functioning family at their core.

Homesteading is a group activity.

A few years ago, I was buying three hundred feet of steel cable to build the tram to our homestead. I was going to trust my wife and kids to this cable on a daily basis, and a dunk from twenty feet into our freezing, rushing river might not be survivable in August, let alone December.

I ended up buying good, quality cable. Now, 99 percent of all cable you'll ever see is comprised of six strands of wire rope wrapped around a single, straight strand called the core. Without its core, all of those strands become less productive. As pressure and stress are added to the cable's load, each strand relies on the core more to keep everything together, united, and strong. I looked at this six-strand cable as if it represented the six members of my family. And then I started thinking about all those families who homesteaded in North America.

As those farmers made the move from farm to factory and ultimately to the office over the last century, they left significant core values behind. In retrospect, each transitional step toward "progress" has found us working harder and harder for wages that are worth less and less. As commuters move farther away in search of affordable homes, commuting

even longer distances becomes the norm. Suddenly that nine-to-five has essentially become a seven-to-eight. Now Mom and Dad are stressed to the max, the kids resent and…