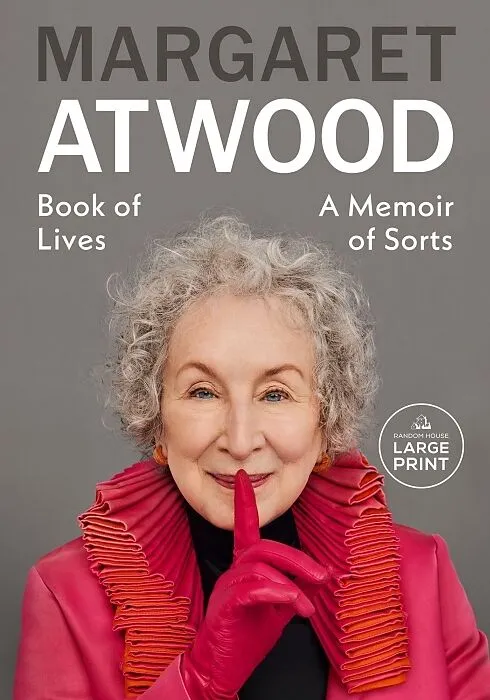

Book of Lives. Large Print Edition

Beschreibung

Coming this fall from Doubleday, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Autorentext Margaret Atwood is the author of more than fifty books of fiction, poetry, and critical essays. Her novels include Cat's Eye, The Robber Bride, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 41.20

- Fester EinbandCHF 37.20

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Coming this fall from Doubleday, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Autorentext

Margaret Atwood is the author of more than fifty books of fiction, poetry, and critical essays. Her novels include Cat's Eye, The Robber Bride, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin, and the MaddAddam trilogy. Her 1985 classic, The Handmaid’s Tale, was followed in 2019 by a sequel, The Testaments, which was a global number one bestseller and won the Booker Prize. Atwood has won numerous awards, including the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Imagination in Service to Society, the Franz Kafka Prize, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, the PEN America Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. In 2019, she was made a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour for services to literature. She lives in Toronto.

Klappentext

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • LONGLISTED FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE AWARD • NAMED A NOTABLE BOOK OF THE YEAR BY THE NEW YORK TIMES AND THE WASHINGTON POST • How does the greatest writer of our time tell her own story?

"The most spectacular, hilarious, and generous autobiography of the last quarter century–or ever."—The Boston Globe

Raised by scientifically minded parents, Margaret Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec: a vast playground for her entomologist father and independent, resourceful mother. It was an unfettered and nomadic childhood, sometimes isolated but also thrilling and beautiful.

From this unconventional start, Atwood unfolds the story of her life, linking key moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape, from the cruel school year that would become Cat’s Eye to the unease of 1980s Berlin, where she began The Handmaid’s Tale. In pages alive with the natural world, reading and books, major political turning points, and her lifelong love for the charismatic writer Graeme Gibson, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood stars, and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.

As she explores her past, Atwood reveals more and more about her writing, the connections between real life and art—and the workings of one of our very greatest imaginations.

Leseprobe

CHAPTER 1

FAREWELL TO NOVA SCOTIA

A THING MY MOTHER SAID:

MY MOTHER: Because our father’s name was Dr. Killam, kids at school used to tease us. They’d say, “Killam, Skin’em, and Eat’em.”

ME: Did they hurt your feelings?

MY MOTHER: Pooh. I wouldn’t give them the satisfaction.

A THING MY FATHER SAID:

“How long would it take two fruit flies, reproducing unchecked, to cover the entire Earth to a depth of two miles?”

(I don’t remember the answer to this, but it was a remarkably short time.)

Both my parents were from Nova Scotia. My father was born in 1906, my mother in 1909. Counting forward, you can see they would have been entering the job market just as the Great Depression of the 1930s was at its height. Coupled with that was the general decline of the Canadian Maritimes: Halifax had been a prosperous seaport in the nineteenth century, but then came the building of the railroads and the shift of the financial gravitational centre, first to Montreal, then Toronto. The city had a brief uptick during the First World War; later, after my parents had left Nova Scotia, it was the staging area for the Atlantic convoys due to its sheltered harbour. Some in Nova Scotia benefited from American Prohibition in the 1920s and early 1930s. A brisk smuggling business had fishing boats picking up booze from Saint-Pierre and Miquelon—French territory—and running it into the deep coves and estuaries of Maine. If Uncle Bill suddenly got a new roof on his barn, you didn’t ask him how he’d paid for it. But to profit from that trade you had to have a boat. Those who didn’t have boats were out of luck.

A joke from that time: “What’s the chief export of Nova Scotia?” “Brains.”

During those years, many Nova Scotians moved west in search of jobs. My parents were part of that exodus.

All the Nova Scotians I’ve known have been universally homesick. I’m not sure why, but so it has been. Both of my parents always referred to Nova Scotia as “home,” causing some confusion for me as a child: If Nova Scotia was “home,” where was I living? In some sort of not-home?

Ours is a family shrub, not a family tree. If you have roots in the Maritimes and meet someone else with similar roots, you find yourself picking your way through the shrubbery. Who was your father, who was your mother, grandfather, grandmother, from where, and so on, until you establish the fact that you are related. Or not. This can go on for some time.

So here’s the deep dive.

Nova Scotia, far from being uniformly Scottish in origin as the name might imply, was remarkably diverse. The Mi’kmaq lived there and still do, and are related to other Indigenous groups in New Brunswick and Maine. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Nova Scotia was one of the first parts of what is now Canada to receive an influx of Europeans. French explorers; and French settlers and farmers who called themselves Acadian in honour of the comparatively idyllic place they found themselves in; then New Englanders who’d been enticed by cheap land. Later came a number of people who had been on the losing side of the American Revolution. These included the Free Blacks, who’d fought on the side of the British. Collectively, these immigrants from the States were known as United Empire Loyalists. Some of these were entangled in our family shrubbery.

Just before the Loyalists came German and French Protestants who’d been welcomed by the British during the French and Indian War with New France. Catholic New France—including Vermont and New Brunswick and what is now Quebec—was raiding the Protestant New England colonies with the help of its Indigenous allies, and vice versa. New England had the help of the British Army, while the French colonies were not so well supplied. Finally, in 1759, General Wolfe took Quebec City and New France fell to Britain. The New England colonists had no more need of the British Army, and did not see why they should be so heavily taxed. Result: The American Revolution, no taxation without representation, over-investment on the American side by the French monarchy, French debt, then the French Revolution.

While the wars were going on, the British had wanted to stuff as many Protestants as possible into Nova Scotia. One of these French Protestants joined our ancestral line. So did some Scots from the Highland Clearances in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period during which many small tenant farmers got turfed out of their age-old communities by their own clan chiefs. This was not only fallout from the defeat of the Scots in the 1746 Jacobite rising but was also a result of the spread of profitable sheep farming. I used to joke that I was descended from a long line of folks—going back to the Puritans, but not limited to them—who’d been kicked out of other countries for being contentious, or heretical, or indigent, or otherwise disagreeable.

Here are some of the names from the family shrubbery: Atwoods, Killams, Websters, McGowans, Lewises (from Wales), Nickersons, Moreaus, Robinsons, Chases. Those are just a few of the branches. If you go into the shrubbery, don’t get lost. It’s tangled.

The first of my father’s family to reach Nova Scotia’s South Shore came from Cape Cod. Cape Cod is still crawling with Atwoods, descended from those who arrived in the early seventeenth century, either…