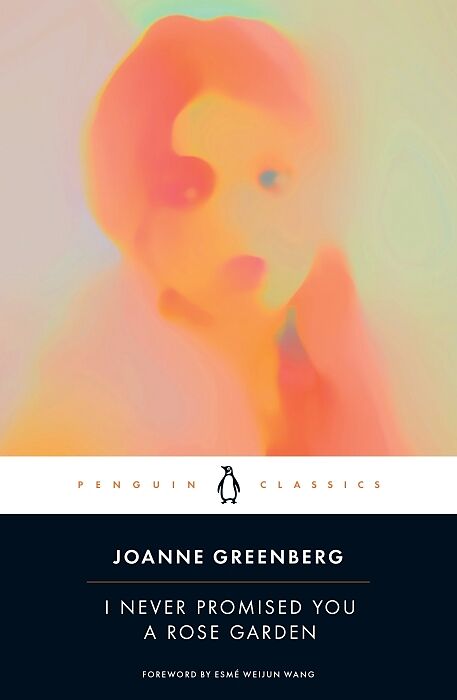

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden

Beschreibung

“I adore this book. . . . I continue to marvel at how Greenberg makes visceral the agony of psychosis. . . . [She] is not afraid to challenge the reader with a true view of the so-called sane world, to hold a crazy candle to reality, and to say, What can...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 21.10

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

“I adore this book. . . . I continue to marvel at how Greenberg makes visceral the agony of psychosis. . . . [She] is not afraid to challenge the reader with a true view of the so-called sane world, to hold a crazy candle to reality, and to say, What can we see now? Is the darkness only inside, or is it outside, too?” ―Esmé Weijun Wang, from the Foreword

“Convincing and emotionally gripping.” ―The New York Times

“Marvelous . . . With a courage that is sometimes breathtaking . . . [Greenberg] makes a faultless series of discriminations between the justifications for living in an evil and complex reality and the justifications for retreating into the security of madness.” ―The New York Times Book Review

“A rare and wonderful insight into the dark kingdom of the mind.” ―Chicago Tribune

“[Joanne Greenberg] is a living example of someone who refused the fate prescribed to her and chose instead to be many other things: clever, attentive, kind, iconoclastic, and the author of more than fifteen books on wildly varying topics. Her life as a recovered patient is not a glamorous or a tragic or a particularly scary one--but it might be a truer one.” ―The New Republic

Autorentext

Joanne Greenberg; Foreword by Esmé Weijun Wang; Afterword by Joanne Greenberg

Klappentext

The multimillion-copy bestselling modern classic of autobiographical fiction about a young woman's struggle with mental illness, featuring a new foreword by Esmé Weijun Wang, the New York Times bestselling author of The Collected Schizophrenias

A Penguin Classic

Hailed by The New York Times as "convincing and emotionally gripping" upon its original publication in 1964, Joanne Greenberg's semiautobiographical novel, originally published under the pen name Hannah Green, stands as a timeless and unforgettable portrait of mental illness. Enveloped in the dark inner kingdom of her schizophrenia, sixteen-year-old Deborah is haunted by private tormentors that isolate her from the outside world. With the reluctant and fearful consent of her parents, she enters a mental hospital, where she will spend the next three years battling to regain her sanity with the help of a gifted psychiatrist. As Deborah struggles toward the possibility of the "normal" life she and her family hope for, the reader is inexorably drawn into her private suffering and deep determination to confront her demons.

A modern classic, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden remains every bit as poignant, gripping, and relevant today as when it was first published.

Story Locale: Chicago, IL

Leseprobe

Chapter One

They rode through the lush farm country in the middle of autumn, through quaint old towns whose streets showed the brilliant colors of turning trees. They said little. Of the three, the father was most visibly strained. Now and then he would place bits of talk into the long silences, random and inopportune things with which he himself seemed to have no patience. Once he demanded of the girl, whose face he had caught in the rearview mirror: "You know, don't you, that I was a fool when I married-a damn young fool who didn't know about bringing up children-about being a father?" His defense was half attack, but the girl responded to neither. The mother suggested that they stop for coffee. This was really like a pleasure trip, she said, in the fall of the year with their lovely young daughter and such beautiful country to see.

They found a roadside diner and turned in. The girl got out quickly and walked toward the restrooms behind the building. As she walked the heads of the two parents turned quickly to look after her. Then the father said, "It's all right."

"Should we wait here or go in?" the mother asked aloud, but to herself. She was the more analytical of the two, planning effects in advance-how to act and what to say-and her husband let himself be guided by her because it was easy and she was usually right. Now, feeling confused and lonely, he let her talk on-planning and figuring-because it was her way of taking comfort. It was easier for him to be silent.

"If we stay in the car," she was saying, "we can be with her if she needs us. Maybe if she comes out and doesn't see us . . . But then it should look as if we trust her. She must feel that we trust her. . . ."

They decided to go into the diner, being very careful and obviously usual about their movements. When they had seated themselves in a booth by the windows, they could see her coming back around the corner of the building and moving toward them; they tried to look at her as if she were a stranger, someone else's daughter to whom they had only now been introduced, a Deborah not their own. They studied the graceless adolescent body and found it good, the face intelligent and alive, but the expression somehow too young for sixteen.

They were used to a certain bitter precocity in their child, but they could not see it now in the familiar face that they were trying to convince themselves they could estrange. The father kept thinking: How could strangers be right? She's ours . . . all her life. They don't know her. It's a mistake-a mistake!

The mother was watching herself watching her daughter. "On my surface . . . there must be no sign showing, no seam-a perfect surface." And she smiled.

In the evening they stopped at a small city and ate at its best restaurant, in a spirit of rebellion and adventure because they were not dressed for it. After dinner, they went to a movie. Deborah seemed delighted with the evening. They joked through dinner and the movie, and afterward, heading out farther into the country darkness, they talked about other trips, congratulating one another on their recollection of the little funny details of past vacations. When they stopped at a motel to sleep, Deborah was given a room to herself, another special privilege for which no one knew, not even the parents who loved her, how great was the need.

When they were sitting together in their room, Jacob and Esther Blau looked at each other from behind their faces, and wondered why the poses did not fall away, now that they were alone, so that they might breathe out, relax, and find some peace with each other. In the next room, a thin wall away, they could hear their daughter undressing for bed. They did not admit to each other, even with their eyes, that all night they would be guarding against a sound other than her breathing in sleep-a sound that might mean . . . danger. Only once, before they lay down for their dark watch, did Jacob break from behind his face and whisper hard in his wife's ear, "Why are we sending her away?"

"The doctors say she has to go," Esther whispered back, lying rigid and looking toward the silent wall.

"The doctors." Jacob had never wanted to put them all through the experience, even from the beginning.

"It's a good place," she said, a little louder because she wanted to make it so.

"They call it a mental hospital, but it's a place, Es, a place where they put people away. How can it be a good place for a girl-almost a child!"

"Oh, God, Jacob," she said, "how much did it take out of us to make the decision? If we can't trust the doctors, who can we ask or trust? Dr. Lister says that it's the only help she can get now. We have to try it!" Stubbornly she turned her head again, toward the wall.

He was silent, conceding to her once more; she was so much quicker with words than he. They said good night; each pretended to sleep, and lay, breathing deeply to delude the other, eyes aching through the darkness, watching.

On the other side of the wall Deborah stretched to sleep. The Kingdom of Yr had a kind of neutral place, which was ca…