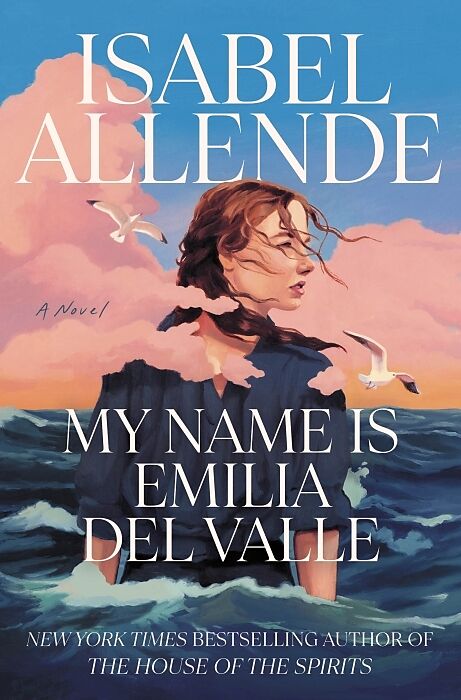

My Name Is Emilia del Valle

Beschreibung

In this spellbinding historical novel from the In San Francisco in 1866, an Irish nun, abandoned following a torrid relationship with a Chilean aristocrat, gives birth to a daughter named Emilia del Valle. Raised by a loving stepfather, Emilia grows into an in...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 33.20

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

In this spellbinding historical novel from the In San Francisco in 1866, an Irish nun, abandoned following a torrid relationship with a Chilean aristocrat, gives birth to a daughter named Emilia del Valle. Raised by a loving stepfather, Emilia grows into an independent thinker and a self-sufficient young woman. To pursue her passion for writing, she is willing to defy societal norms. At the age of seventeen, she begins to publish pulp fiction using a man’s pen name. When these fictional worlds can no longer satisfy her sense of adventure, she turns to journalism, convincing an editor at As she proves herself, her restlessness returns, until an opportunity arises to cover a brewing civil war in Chile. She seizes it, as does Eric, and while there, she meets her estranged father and delves into the violent confrontation in the country where her roots lie. As she and Eric discover love, the war escalates and Emilia finds herself in extreme danger, fearing for her life and questioning her identity and her destiny. A riveting tale of self-discovery and love from one of the most masterful storytellers of our time, <My Name Is Emilia del Valle< introduces a character who will never let hold of your heart.

Autorentext

Isabel Allende, born in Peru and raised in Chile, is a novelist, feminist, and philanthropist. She is one of the most widely read authors in the world, having sold more than eighty million copies of her books across forty-two languages. She is the author of many bestselling and critically acclaimed books, including The Wind Knows My Name, Violeta, A Long Petal of the Sea, The House of the Spirits, Of Love and Shadows, Eva Luna, and Paula. In addition to her work as a writer, Allende devotes much of her time to human rights causes. She has received fifteen honorary doctorates, has been inducted into the California Hall of Fame, and received the PEN Center USA’s Lifetime Achievement Award and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement. In 2014, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, and in 2018, she received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation. Allende lives in California with her husband and dogs.

Klappentext

NATIONAL BESTSELLER • In this “stunning” (People), “riveting” (Entertainment Weekly) historical novel, a young writer journeys to South America to uncover the truth about her father—and herself.

“All of Allende’s books, My Name Is Emilia del Valle included, have the epic feel of a major Hollywood film.”—Associated Press

AN NPR AND NEW YORKER BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

In San Francisco in 1866, an Irish nun, abandoned following a torrid relationship with a Chilean aristocrat, gives birth to a daughter named Emilia del Valle. Raised by a loving stepfather, Emilia grows into an independent thinker and a self-sufficient young woman.

To pursue her passion for writing, she is willing to defy societal norms. At the age of seventeen, she begins to publish pulp fiction using a man’s pen name. When these fictional worlds can no longer satisfy her sense of adventure, she turns to journalism, convincing an editor at The Daily Examiner to hire her. There she is paired with another talented reporter, Eric Whelan.

As she proves herself, her restlessness returns, until an opportunity arises to cover a brewing civil war in Chile. She seizes it, as does Eric, and while there, she meets her estranged father and delves into the violent confrontation in the country where her roots lie. As she and Eric discover love, the war escalates and Emilia finds herself in extreme danger, fearing for her life and questioning her identity and her destiny.

A riveting tale of self-discovery and love from one of the most masterful storytellers of our time, My Name Is Emilia del Valle introduces a character who will never let hold of your heart.

Leseprobe

1

The day I turned seven years old, April 14, 1873, my mother, Molly Walsh, dressed me in my Sunday best and brought me to Union Square to have my portrait taken. The only existing photograph of my childhood depicts me standing beside a harp with the terrified expression of a man on the gallows, a result of the long minutes spent staring into the black box of the camera holding my breath, followed by the startle of the flashbulb. I should clarify that I do not know how to play any instrument; the harp was merely one of the dusty theatrical props crowded into the photography studio alongside cardboard columns, Chinese vases, and a stuffed horse.

The photographer was a small mustachioed Dutchman who had made a good living at his trade since the times of the gold rush when the miners came down from the mountains to deposit their nuggets in the banks and have their portraits taken to send home to their all-but-forgotten families. Gold fever soon died down, but San Francisco’s upper-class patrons still frequented the studio to pose for posterity. My family didn’t fall into that category, but my mother had her own reasons for wanting a photo of her daughter. She haggled on the price of the portrait, more on principle than out of real necessity; I’ve never known her to purchase anything without attempting to obtain a discount.

“While we’re here, we’ll go and see the head of Joaquín Murieta,” she told me as we left the Dutchman’s studio.

At the opposite end of the square, near the entrance to Chinatown, she bought me a cinnamon roll and led me to the door of an unsanitary tavern. We paid the entrance fee and traversed a long hallway to the rear of the locale. There, a scary thug lifted a heavy curtain and we entered a room hung with lugubrious draperies and lit with altar candles like some ghastly church. There was a table shrouded in black cloth at one end of the space and atop it sat two large glass jars. I cannot recall any further details of the décor because I was paralyzed by fright. My mother seemed euphoric even as I quaked with fear, both hands clutching at her skirts. The first jar held a human hand floating in a yellowish liquid. The second, a man’s decapitated head with the eyelids sewn shut, lips pulled back, teeth barred, and hair standing on end.

“Joaquín Murieta was a bandit. A reprobate, like your father. This is how bandits usually end up,” my mother explained.

It goes without saying that I suffered horrible nightmares that night. I was even feverish, but my mother was of the opinion that unless a person was bleeding, there was no need to intervene. The following day, wearing the same dress and the same cursed lace-up boots that pinched terribly, since I had been forcing my feet into them for the past two years, we picked up my portrait and walked to the wealthy part of town, a neighborhood I had never set foot in before. Cobbled streets wended their way up the hills flanked by stately homes overlooking rose gardens and tidily trimmed hedges, coach houses stocked with glossy horses, not a single beggar in sight.

Up to that point, my entire existence had transpired within the confines of the Mission District, that multicolored, polyglot multitude of emigrants from Germany, Ireland, and Italy; Mexicans who had always lived in California; and a considerable cohort of Chileans who came with the gold rush in 1848 and, several decades later, were still as poor as when they had first arrived. They never saw any gold. If they did find anything in the mines, it was snatched from them by the whites who arrived a year later. Many returned to their homeland with nothing more than fabulous tales to tell. Others stayed because the return trip was long and costly. The Mission …