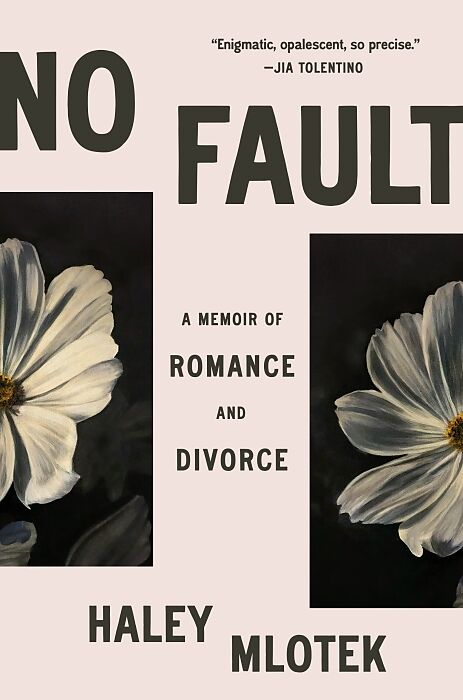

No Fault

Beschreibung

An intimate and candid account of one of the most romantic and revolutionary of relationships, divorce--from a brilliant, award-winning young writer When Haley Mlotek was ten years old, she told her mother to leave her father. Divorce was all around her. Her m...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 29.50

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

An intimate and candid account of one of the most romantic and revolutionary of relationships, divorce--from a brilliant, award-winning young writer When Haley Mlotek was ten years old, she told her mother to leave her father. Divorce was all around her. Her mother ran a mediation and marriage counseling practice out of Mlotek’s childhood home, and she spent her preteen years answering the phones and typing out parenting plans for couples in the process of leaving each other. She grew up with the sense that divorce was an outcome to both resist and desire, an ordeal that promised something better on the other side of something bad. But when she herself went on to marry--and then divorce--the man she had been with for twelve years, suddenly, she had to reconsider everything she thought she understood about divorce. Deftly combining her personal story with wry, searching social and literary exploration, Brilliant, funny, and unflinchingly honesty, <No Fault <is a kaleidoscopic look at marriage, secrets, ambitions, and what it truly means to love and live with uncertainty, betrayal, and hope.

Autorentext

Haley Mlotek is a writer, editor, and organizer. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Nation, Bookforum, The Paris Review, Columbia Journalism Review, Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Hazlitt, and n+1, among others. She is a founding member of the Freelance Solidarity Project in the National Writers Union, teaches in the English and Journalism departments at Concordia University, and is the editorial lead at Feeld. Previously, Mlotek was the deputy editor of SSENSE, the style editor of MTV News, the editor of The Hairpin, and the publisher of WORN Fashion Journal.

Klappentext

**One of NPR’s 2025 “Books We Love”

A Vogue & Vulture Best Book of the Year (So Far)

“Enigmatic, opalescent, so precise.” —Jia Tolentino

“An investigation, an invocation, a mood.” —Becca Rothfeld, The Washington Post

“A personal accounting of heartache. . . . Mlotek’s writing reaches toward — and actually meets — poetry.” —Alissa Bennett, The New York Times Book Review

“A cool appraisal of millennial divorce.” —Emma Alpern, Vulture

An intimate and candid account of one of the most romantic and revolutionary of relationships: divorce**

Divorce was everything for Haley Mlotek. As a child, she listened to her twice-divorced grandmother tell stories about her “husbands.” As a pre-teen, she answered the phones for her mother’s mediation and marriage counseling practice and typed out the paperwork for couples in the process of leaving each other. She grew up with the sense that divorce was an outcome to both resist and desire, an ordeal that promised something better on the other side of something bad. But when she herself went on to marry—and then divorce—the man she had been with for twelve years, suddenly, she had to reconsider her generation’s inherited understanding of the institution.

Deftly combining her personal story with wry, searching social and literary exploration, No Fault is a deeply felt and radiant account of 21st century divorce—the remarkably common and seemingly singular experience, and what it reveals about our society and our desires for family, love, and friendship. Mlotek asks profound questions about what divorce should be, who it is for, and why the institution of marriage maintains its power, all while charting a poignant and cathartic journey away from her own marriage towards an unknown future.

Brilliant, funny, and unflinchingly honest, No Fault is a kaleidoscopic look at marriage, secrets, ambitions, and what it means to love and live with uncertainty, betrayal, and hope.

A MOST ANTICIPATED BOOK OF 2025: Vogue, Vulture, Harper’s Bazaar, W, Bustle, Lit Hub, The Millions

Leseprobe

I was married on a cold day in December. Thirteen months later my husband moved out. We decided to separate in November after agreeing to spend the holidays with our families. We told just a few friends, thinking maybe this was temporary. But the weeks between were a problem. After over a decade celebrating the anniversary of the spring night he kissed me—a hotel elevator, a high school trip—now there was the date that marked the night he kissed me in his mother’s living room, where we exchanged rings and signed papers. We had been together for thirteen years, lived together for five, and now, were we supposed to celebrate the one year we barely managed to stay married? Well—we made dinner reservations. Not knowing what to do or where to look, we talked about what we had done that day, our jobs. I tried to be careful but couldn’t help making some reference to our situation, so he would know the strangeness was not lost on me. “What was your favorite part of being married?” I asked, smiling to shield the was. He talked about our wedding, our move to a new city, and then he asked me the same question.“ Being a family,” I said, and cried, but only a little.

We flew home. We saw our families, and we fought. We were cat-sitting for a friend and my husband spent his nights elsewhere. The cats had recently been kittens and were not yet adjusted to their adult sizes. They ran and played as though they might not knock over water glasses or pull out electrical cords. They were cute and they kept me awake all night. In the mornings my husband—my handsome husband, I sometimes thought when I saw him, even after we decided to separate, because he was, still, both—would come home and feed them, and they would immediately fall asleep. God, I hated those cats.

On the first day of the New Year we flew back to our apartment. By the third day I was living there alone.

Every generation of North American is now alive at a moment when they have access to what is usually called “no‑fault” divorce, the legal dissolution of marriage that does not require a reason beyond choice. Those who have lived long enough to know the difference understand the significance of this freedom; those who will never know the difference have inherited a profound question of what divorce should be, who it is for, and why the institution of marriage maintains its power.

I have looked for guidance everywhere but real life. Through fiction and film, through gossip and conversation, through research about the past and speculation about the future, and most of all through work—always working, always writing. I have always preferred reading to reality. In reading, there’s the possibility for more than just what’s on the page, or the screen, or coming through the other end of the phone. In turning over what happened, the facts are just details, significance just interpretation. This is evasive, and better still, very effective. I want you to ask if I’ve read Anna Karenina. I do not want you to ask what I would do for love.

There are some incidents that seem to matter most and that becomes the story. Sometimes there’s risk or danger, tears or blood. A story about broken plates, the screen in the window, the sound of his voice. But what happened after? That is what I want to know.

When they both decided they had had enough, I want to ask: And then what? Did they go to bed, and if so, did they sleep in the same bed? What was it like the next morning—did they make coffee, or say goodbye before leaving for work? I prefer to see myself as audience, watching as though it didn’t happen to me. When remembering, I can see that in my story the worst happened twice, maybe three times. Then it was over. …