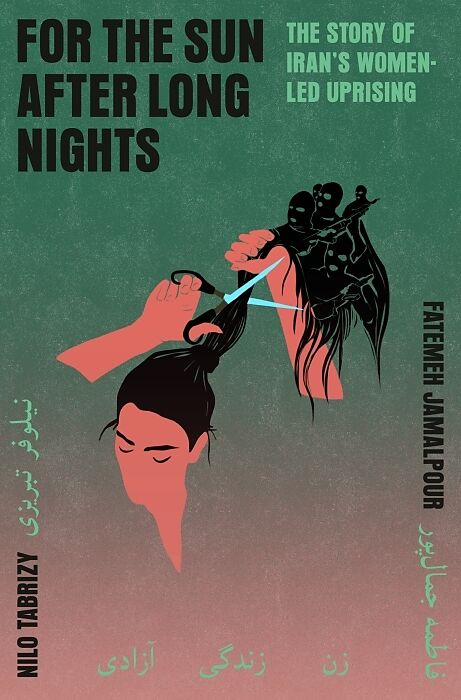

For the Sun After Long Nights

Beschreibung

A moving exploration of the 2022 women-led protests in Iran, as told through the interwoven stories of two Iranian journalists In September 2022, a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Jîna Amini, died after being beaten by police officers who arrested her for not...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 31.60

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

A moving exploration of the 2022 women-led protests in Iran, as told through the interwoven stories of two Iranian journalists In September 2022, a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Jîna Amini, died after being beaten by police officers who arrested her for not adhering to the Islamic Republic’s dress code. Her death galvanized thousands of Iranians--mostly women--who took to the streets in one of the country’s largest uprisings in decades: the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. Despite the threat of imprisonment or death for her work as a journalist covering political unrest, state repression, and grassroots activism in Iran--which has led to multiple interrogation sessions and arrests--Fatemeh Jamalpour joined the throngs of people fighting to topple Iran’s religious extremist regime. And across the globe, Nilo Tabrizy, who emigrated from Iran with her family as a child, covered the protests and state violence, knowing that spotlighting the women on the front lines and the systemic injustice of the Iranian government meant she would not be able to safely return to Iran in the future. Though they had met only once in person, Nilo and Fatemeh corresponded constantly, often through encrypted platforms to protect Fatemeh. As the protests continued to unfold, the sense of sisterhood they shared led them to embark on an effort to document the spirit and legacy of the movement, and the history, geopolitics, and influences that led to this point. At once deeply personal and assiduously reported, <For the Sun After Long Nights< offers two perspectives on what it means to cover the stories that are closest to one’s heart--both in the forefront and from afar

Autorentext

FATEMEH JAMALPOUR is a feminist freelance journalist banned from working in Iran by the Ministry of Intelligence. She has contributed to The Sunday Times, The Paris Review, and the Los Angeles Times and previously worked with BBC World News in London and Shargh newspaper in Tehran. Fatemeh was a 2024–25 Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan.

NILO TABRIZY an investigative reporter at The Washington Post. She works for the Visual Forensics team, where she covers Iran using open-source methods. Previously, she was a video journalist at The New York Times, covering Iran, race and policing, abortion access, and more. She is an Emmy nominee and the 2022 winner of the Front Page Award for Online Investigative Reporting. Nilo received her M.S. in Journalism from Columbia University and her B.A. in Political Science and French from the University of British Columbia.

Klappentext

**LONGLISTED FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD • A moving exploration of the 2022 women-led protests in Iran, as told through the interwoven stories of two Iranian journalists

“Unlike anything I’ve read . . . A searing, courageous, and ultimately beautiful book filled with the spirit of the movement that it covers.” —Ben Rhodes, author of The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House**

In September 2022, a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Jîna Amini, died after being beaten by police officers who arrested her for not adhering to the Islamic Republic’s dress code. Her death galvanized thousands of Iranians—mostly women—who took to the streets in one of the country’s largest uprisings in decades: the Woman, Life, Freedom movement.

Despite the threat of imprisonment or death for her work as a journalist covering political unrest, state repression, and grassroots activism in Iran—which has led to multiple interrogation sessions and arrests—Fatemeh Jamalpour joined the throngs of people fighting to topple Iran’s religious extremist regime. And across the globe, Nilo Tabrizy, who emigrated from Iran with her family as a child, covered the protests and state violence, knowing that spotlighting the women on the front lines and the systemic injustice of the Iranian government meant she would not be able to safely return to Iran in the future.

Though they had met only once in person, Nilo and Fatemeh corresponded constantly, often through encrypted platforms to protect Fatemeh. As the protests continued to unfold, the sense of sisterhood they shared led them to embark on an effort to document the spirit and legacy of the movement, and the history, geopolitics, and influences that led to this point. At once deeply personal and assiduously reported, For the Sun After Long Nights offers two perspectives on what it means to cover the stories that are closest to one’s heart—both in the forefront and from afar.

Leseprobe

NILO

FOR STUDENTS. FOR THE FUTURE.

On September 26, 2022 , I got my first email from Fatemeh in nine months. She had just been summoned and interrogated by the Ministry of Intelligence, who had threatened her with two years of jail time for her journalism at the BBC that was critical of the regime. “I am not scared,” Fatemeh wrote. “Something like hope is rising among us, hope for changes, for woman, life, freedom, for you visiting me in Tehran soon.”

The last time I had heard from her was in 2021, when she was preparing to return to Iran after a stint in London and told me she was cutting off contact with me completely. “It’s not safe to communicate with you. You won’t hear from me. Take care, abji joon. Boos boos,” she wrote, calling me abji, her sister, and sending digital kisses my way. She knew that her return meant that intelligence and security forces would snatch her up and start interrogating her about her work as a journalist abroad, which had become common practice for the regime in our increasingly dictatorial homeland.

I got her email in the middle of my workday at The New York Times, for which I had begun to cover the protests surging in Iran. I was working on my first story: a visual analysis of the themes of the demonstrations that were yet to swell into an uprising. My days were spent meticulously researching, organizing, and archiving videos and images shared by Iranians on social media as the street protests started to take shape. In the beginning, everything felt like a fever—nonstop, urgent, and somewhat surreal. I slept poorly and woke up with a heaviness in my body each morning, stopping myself from falling into a deep sleep for fear of missing something from a handful of time zones away. When I saw Fatemeh’s name in my inbox, I couldn’t believe that it was her. If the Islamic Republic found out that she was communicating with a Western journalist, Fatemeh could have been imprisoned for years for conspiring with “the enemy.” But like other Iranians who were flooding the streets at the time, Fatemeh was evolving into a more defiant version of herself—one who was willing to accept the very real cost of risking her life and freedom.

By November 2022, social media continued to be full of footage of the protests. Iranians were ripping and torching posters of the Islamic Republic’s cultlike leaders, women were cutting their hair while weeping in the middle of crowds, and mourners held funerals for people killed by the state during protests. In Tehran, the country’s capital, elderly women marched up to the police, daring them to put them in handcuffs; members of the brave working class led historic strikes that shut down the northwestern city of Tabriz’s grand bazaar; and even in Mashhad, a religious city in the northeast that has historically supported the regime, Iranians were chanting, “Death to the Islamic Republic!” in the streets.

Led by young women and other members of Gen Z, at least two million Iranians poured into the streets in the largest and most widespread uprising that the Islamic Republic has seen in i…