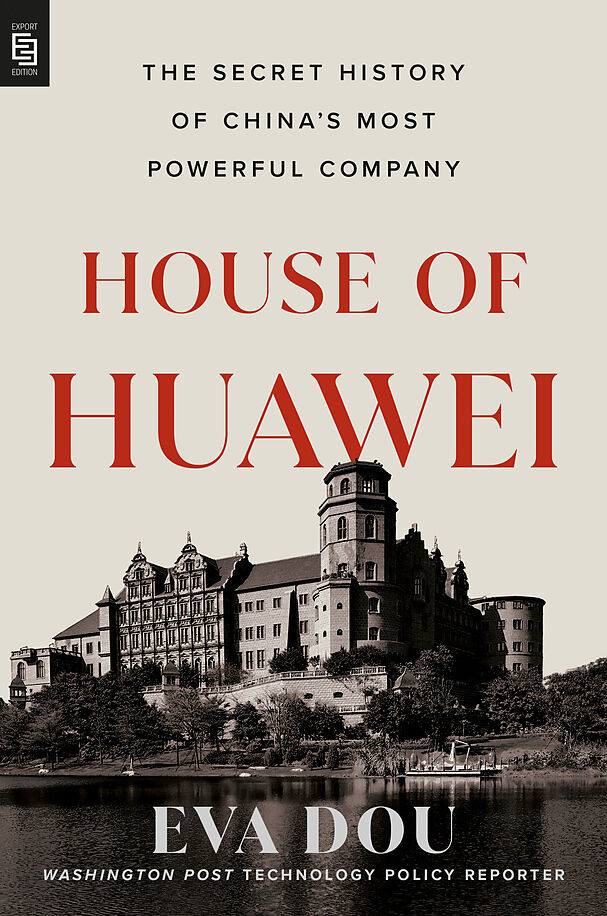

House of Huawei

Beschreibung

The untold story of the mysterious company that shook the world. On the coast of southern China, an eccentric entrepreneur spent three decades steadily building an obscure telecom company into one of the world’s most powerful technological empires with h...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 22.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

The untold story of the mysterious company that shook the world. On the coast of southern China, an eccentric entrepreneur spent three decades steadily building an obscure telecom company into one of the world’s most powerful technological empires with hardly anyone noticing. This all changed in December 2018, when the detention of Meng Wanzhou, Huawei Technologies’ female scion, sparked an international hostage standoff, poured fuel on the US-China trade war, and suddenly thrust the mysterious company into the global spotlight. In <House of Huawei<, <Washington Post< technology reporter Eva Dou pieces together a remarkable portrait of Huawei’s reclusive founder, Ren Zhengfei, and how he built a sprawling corporate empire--one whose rise Western policymakers have become increasingly obsessed with halting. Based on wide-ranging interviews and painstaking archival research, <House of Huawei< dissects the global web of power, money, influence, surveillance, bloodshed, and national glory that Huawei helped to build--and that has also ensnared it.

Autorentext

Eva Dou is The Washington Post's China business and economy correspondent. A Detroit native, she previously spent seven years reporting on politics and technology for the Wall Street Journal in Beijing and Taipei, Taiwan. She is currently based in Washington D.C.

Klappentext

The untold story of the mysterious family dynasty at the center of China’s Huawei.

On December 1, 2018, Meng Wanzhou, daughter of Ren Zhengfei, founder and CEO of China’s most powerful company, Huawei Technologies, was detained at the request of U.S. authorities as she prepared to board a flight out of Vancouver, Canada. The detention of Huawei’s female scion set the U.S.-China trade skirmish on fire— and, for the first time, revealed the Ren family’s prominence in Beijing’s power structure.

In The Listening State, acclaimed Washington Post reporter Eva Dou exposes the untold story of the rise of Ren Zhengfei and the mysterious family dynasty at the center of Huawei, whose connections to state apparatus reveal a deeper truth about China’s surveillance web and its global ambitions. Through its technologies, Huawei has helped solidify and enforce China’s growing police state, in which outspoken entrepreneurs like Jack Ma have been silenced, tycoons have disappeared, and executives must put patriotism above profit.

Based on over a decade of on-the-ground reporting and an astonishing trove of confidential documents never published in English, The Listening State paints an epic story of familial and political intrigue that shines a clarifying light on how business and government work together in an authoritarian state, and how companies fit into China’s international ambitions under Xi Jinping.

The story of Ren Zhengfei and Huawei exposes the human face of China’s modern security state and gets to the heart of the central questions of the U.S.-China trade war: How did these turbocharged Chinese companies emerge? Who really controls them? And what does China’s growing surveillance web mean for the Chinese people — and for the rest of the world?

Leseprobe

1

The Bookseller

The Ren Family: 1937-1968

Ren Moxun sold "good books." That was what he and his friends called patriotic literature. They were seeking to inspire their countrymen to heroism at a time when it was urgently needed. They'd considered names like Advancement Bookstore and Pioneering Bookstore before finally settling on July Seventh Bookstore. The reference was obvious: Earlier that year, on July 7, 1937, Japanese troops had crossed the Marco Polo Bridge, captured the capital, and continued their invasion of China. World War II would not come for Europe for another two years, when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland. But here in China, the war was already upon them. Ren Moxun opened up the bookstore in the small town of Rongxian, in southern Guangxi Province, and threw himself into the war effort.

Ren Moxun was around twenty-seven at this time, and he had a high forehead, long cheeks, and bushy eyebrows. The only one among his siblings to have attended university, he cultivated a professorial air and wore horn-rimmed spectacles. He revered books, schooling, and the written word, a predisposition he would pass down to his seven children. At the time he opened his bookstore, reading was still a hobby for the privileged elite. If you pulled five people off the street at random, you'd be lucky if one could read. Chinese script was difficult to learn: it had no alphabet, and you had to memorize each word, one by one. Still, there was enough interest in Rongxian for a bookstore. Ren Moxun stocked revolutionary titles from a supplier in Guilin: Karl Marx's Das Kapital, Vladimir Lenin's The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, the complete works of the modern Chinese thinker Lu Xun. He and his colleagues placed a bench at the front so that frugal students could sit and read for free. Outside the bookstore, they propped up a blackboard to scrawl news of the war, something of an unofficial village newspaper. They started a political reading club too, which gathered for spirited discussions.

In his day job, Ren Moxun served as an accountant for a Nationalist military factory supporting the fight against Japan. The Nationalists, China's rulers at the time, were also embroiled in a civil war against Mao Zedong's Communists, who were seeking to overthrow them with the help of the peasantry. As they fought Japan's invasion, the two sides had brokered a delicate truce, an agreement Ren Moxun strongly endorsed. When one faction of Communist revolutionaries in his town began advocating to end the détente with the Nationalists, he denounced them as traitors. These were tense times. People disagreed on what was the right path for the nation, on who was friend or foe, on whether a book was a "good book" or not. One day in March 1938, some Nationalist officers searched the bookstore and pulled out a big pile of books that they demanded not be sold. Ren Moxun and his colleagues found a clever workaround. They piled the banned books into a vitrine and scrawled a sign on it: Inside This Cabinet Are Banned Books. As it turned out, the books inside the cabinet sold briskly.

The July Seventh Bookstore was shut down by the Nationalists in the second half of 1939. Its owners held a fire sale to get a last batch of good books out to the people. Ren Moxun considered traveling to Yan'an to join Mao's Communists but found the roads impassable. So he crossed to the rolling hills of the neighboring province, Guizhou, where he found work as a teacher.

Guizhou Province is a hilly region slightly smaller than Missouri, set inland from China's southwestern border with Vietnam. Monsoons sweep the subtropical region each summer, watering the terraced paddies of sticky rice. Cold drizzles continue through the winter. The area's indigenous people were the Bouyei, who spoke their own language and also inhabited northern Vietnam. For centuries, China's emperors considered the area an impoverished borderland where even cooking salt was sometimes in short supply. Even in the modern day, Guizhou retains the reputation of a hardship posting for officials.

In Guizhou, Ren Moxun met a seventeen-year-old named Cheng Yuanzhao. With big brown eyes, round cheeks, and a broad smile, she was also bright and good with numbers. They married, and Cheng Yuanzhao soon became pregnant.

Their son was born in October 1944, and they named him Ren Zhengfei. It was an ambiguous name. Zheng meant "correct," and fei meant "not." "Right or wrong" would be a fair translation. It wasn't like the common, straightforward boys' names. Jiabao meant "family treasure." Jianguo meant "build the nation." But what…