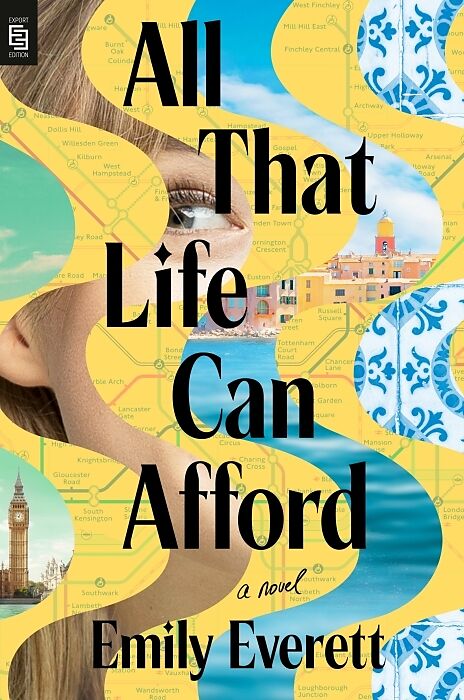

All That Life Can Afford

Beschreibung

A taut and lyrical coming-of-age debut about a young American woman navigating class, lies, and love amid London’s jet-set elite. <I would arrive, blank like a sheet of notebook paper, and write myself new.< Anna first fell in love with Lond...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 19.00

- Fester EinbandCHF 28.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

A taut and lyrical coming-of-age debut about a young American woman navigating class, lies, and love amid London’s jet-set elite.

<I would arrive, blank like a sheet of notebook paper, and write myself new.<

Anna first fell in love with London at her hometown library—its Jane Austen balls a far cry from her life of food stamps and hand-me-downs. But when she finally arrives after college, the real London is a moldy flat and the same paycheck-to-paycheck grind—that fairy-tale life still out of reach.

Then Anna meets the Wilders, who fly her to Saint-Tropez to tutor their teenage daughter. Swept up by the sphinxlike elder sister, Anna soon finds herself plunged into a heady whirlpool of parties and excess, a place where confidence is a birthright. There she meets two handsome young men—one who wants to whisk her into his world in a chauffeured car, the other who sees through Anna’s struggle to outrun her past. It’s like she’s stepped into the pages of a glittering new novel, but what will it cost her to play the part?

Sparkling with intelligence and insight, <All That Life Can Afford< peels back the glossy layers of class and privilege, exploring what it means to create a new life for yourself that still honors the one you’ve left behind.

Autorentext

Emily Everett is an editor and writer from western Massachusetts. Her short fiction appears in The Kenyon Review, Electric Literature, Tin House, and Mississippi Review. She is a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellow in Fiction. Everett grew up on a small family dairy farm, studied English and music at Smith College, and studied abroad for a year at University College London. After graduating, she returned to London to do an M.A. in literature at Queen Mary University of London. She lived and worked in the UK from 2009 to 2013. Everett has been managing editor of The Common, a literary magazine based at Amherst College, since 2016. At The Common, she edits fiction, manages print and online production, and hosts the magazine’s podcast. All That Life Can Afford is her debut novel.

Klappentext

**A REESE’S BOOK CLUB PICK

“An effervescent debut chock full of Austenian nods. Swoonworthy!” —Sarah McCoy, New York Times bestselling author of Mustique Island

“All That Life Can Afford is about love, ambition, and the cost of belonging, and I cannot stop thinking about it.” —Reese Witherspoon

A young American woman navigates class, lies, and love amid London’s jet-set elite.**

I would arrive, blank like a sheet of notebook paper, and write myself new.

Anna first fell in love with London at her hometown library—its Jane Austen balls a far cry from her life of food stamps and hand-me-downs. But when she finally arrives after college, the real London is a moldy flat and the same paycheck-to-paycheck grind—that fairy-tale life still out of reach.

Then Anna meets the Wilders, who fly her to Saint-Tropez to tutor their teenage daughter. Swept up by the sphinxlike elder sister, Anna soon finds herself plunged into a heady whirlpool of parties and excess, a place where confidence is a birthright. There she meets two handsome young men—one who wants to whisk her into his world in a chauffeured car, the other who sees through Anna’s struggle to outrun her past. It’s like she’s stepped into the pages of a glittering new novel, but what will it cost her to play the part?

Sparkling with intelligence and insight, All That Life Can Afford peels back the glossy layers of class and privilege, exploring what it means to create a new life for yourself that still honors the one you’ve left behind.

Leseprobe

1

London

October 2009

I'd never been a great actor or a convincing liar, and an American in Britain will always be scrutinized. I prayed the ticket inspector might think I was an idiot, like all Americans, and not a crook, like most of the people he found on the train to Brighton without a ticket to cover their fare.

Instructors like me had to pay for our own tickets when we traveled to teach weekly SAT-prep sessions at posh boarding schools around the English countryside. Not that you'd know they were schools-more like mansions, refurbed monasteries, drafty Hogwarts-type castles. I'd seen a few already in the four months I'd worked for Kramer Test Prep, but this was the first time I hadn't had the money for my train ticket. I'd formed a weak plan on my way to the station. A shite plan, my flatmate Andre would've said. My first plan had been to borrow the money from him, but he hadn't come home last night.

I'd been poor all my life, in a mundane, lower-working-class way-food stamps, hand-me-downs, pancakes for dinner-and it had bred in me a scrappy sort of boldness that only backfired about fifty percent of the time. Sometimes it seemed like that scrappiness was the only thing I still shared with my father.

The plan was a big risk, but I'd be fired if I missed my class. The travel bonus was £40 each trip; that alone made a typical ten-week class worth more than half a month's rent to me. I'd emailed my supervisor the second the Brighton class was posted, terrified that someone would scoop it up before me. I needed that bonus, even if it only came at the end of the whole class, months later. Months of Saturdays spent on long train rides, cursing everything: the city of Brighton, its icy coastal winds, its historic clifftop boarding school for girls, which I had never heard of but which, when mentioned, impressed my British acquaintances so much-You teach at Roedean?-that I'd quickly learned to use it as social currency.

But it was actual currency I needed, and so far I hadn't seen a pound for my Roedean SAT class.

The shite plan was not complicated. For the first forty-five minutes on the swaying, southbound train, I only had to pretend to sleep. No easy task, my body thrumming with nervous energy. Fare-dodging was no joke here. I'd once seen a ticket inspector rap his knuckles loudly on a train window for ten minutes, trying to wake a "sleeping" man, certainly ticketless. The man later hid in the bathroom, and two stations later the ticket inspector walked him off the train to a waiting semicircle of British Transport Police. Here on an easily revoked student visa, I feared even the lightest brush with the law.

The visa was my ticking clock: I had a year, essentially, to create a solvent, stable life. By this time next year, if I wanted to stay in London, I'd need a completed master's degree, which would earn me a two-year "post-study" work visa. Then I could really begin to make my way in this place that felt more like home than home had in a long time.

On good days I believed it was possible. I could walk through London, my city, and feel that I had achieved something great just by being there. Here I was, taking the Tube, rising on an escalator, emerging on the South Bank, strolling along the Thames and snapping photos and stopping on benches to read my book whenever the sun came out. But then I'd be sitting there, the breeze flipping the pages of my book, not reading but wondering if I had enough to buy a panini and a tea at the little café tucked into the bridge arches near Waterloo. Some days I did have enough, and it was a perfect day, a day I could make a Polaroid snapshot in my mind and store as evidence that I'd made the right choice in coming here. And on days when I didn't have enough, and I went back to the flat and ate spaghetti with butter and stale Parmesan shaken from a can, it was still a perfectly good day for a broke grad student, getting by, not asking for help from my father or anyone.

Finally, I heard the ticket inspector coming …