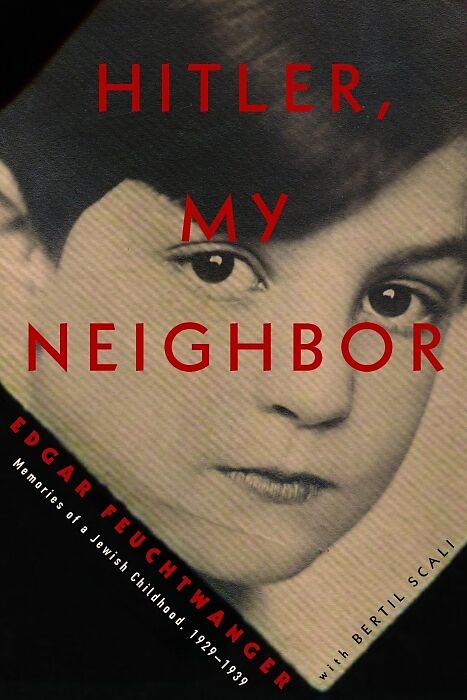

Hitler, My Neighbor

Beschreibung

An eminent historian recounts the Nazi rise to power from his unique perspective as a Jewish boy growing up in Munich with Adolf Hitler as his neighbor. Edgar Feuchtwanger came from a prominent German Jewish family: the only son of a respected editor, and the ...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 29.20

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

An eminent historian recounts the Nazi rise to power from his unique perspective as a Jewish boy growing up in Munich with Adolf Hitler as his neighbor. Edgar Feuchtwanger came from a prominent German Jewish family: the only son of a respected editor, and the nephew of best-selling writer Lion Feuchtwanger. He was a carefree five-year-old, pampered by his parents and his nanny, when Adolf Hitler, the leader of the Nazi Party, moved into the building across the street in Munich. In 1933 his happy young life was shattered. Hitler had been named Chancellor. Edgar’s parents, stripped of their rights as citizens, tried to protect him from increasingly degrading realities. In class, his teacher had him draw swastikas, and his schoolmates joined the Hitler Youth. From his window, Edgar bore witness to the turmoil surrounding the Night of the Long Knives, the Anschluss , and Kristallnacht . Jews were arrested; his father was imprisoned at Dachau. In 1939 Edgar was sent on his own to England, where he would make a new life, start a career and a family, and try to forget the nightmare of his past--a past that came rushing back when he decided, at the age of eighty-eight, to tell the story of his buried childhood and his infamous neighbor.

“The title says it all. A young Jewish boy growing up in Munich in the 1930s, Feuchtwanger writes about living across the street from Hitler, the future mass murderer he could see through his window.” —New York Times Book Review

“Composed of diaristic vignettes, Hitler, My Neighbor offers a singular portrait of 1930s Germany, unique both for its intimate glimpses of Hitler in semi-private moments and for its point of view. The narrative unfolds from a child’s perspective but benefits from an adult historian’s attention to detail.” —Newsweek*

**

“He can’t wrap his mind around the contradictions, but neither can many adults. Illuminating how it was possible for so many to be so confused is the book’s great achievement.” —TheNew Yorker*

“Remarkable.” —Minneapolis Star Tribune

“An intimate look at the horror wrought by Hitler.” —Kirkus Reviews*

**“Feuchtwanger is an excellent writer. He wisely focuses on the senses, an especially significant technique for authors of childhood experiences. He sees the world through the eyes of a child, yet delivers from the aspect of an adult trained in writing history. The result is an exceptionally powerful and emotionally charged story.” —New York Journal of Books*

“Hitler, My Neighbor is a rare look at the conflicted, often horrifying childhood of a Jewish boy in Nazi Germany.” —Book Reporter

“Edgar Feuchtwanger’s captivating memoir brings an enigmatic and terrifying neighbor—glimpsed through a child’s eyes—into the heart of a Jewish family’s home life, where discussions revolve around how to make sense of Germany’s descent into fascism and, ultimately, how to survive it.” —Despina Stratigakos, author of Hitler at Home

Autorentext

Edgar Feuchtwanger was born in Munich in 1924 and immigrated to England in 1939. He studied at Cambridge University and taught history at the University of Southampton until he retired in 1989. His major works include From Weimar to Hitler, Disraeli, *and Imperial Germany 1850–1918*. In 2003 he received the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for promoting Anglo-German relations.

Bertil Scali is a French journalist and writer. He wrote and co-directed a TV documentary about Edgar Feuchtwanger’s childhood in Munich, and is the author of Villa Windsor.

Leseprobe

1929

I like it when she plays this piece for me. A piano minuet. She told me Mozart wrote it when he was my age. I’m five. I listen to the notes, it’s very pretty. I’m on the floor, swimming on the parquet as if it were a lake. The armchairs are boats, the sofa an island and the table a castle. If Mama sees me she’ll scold me and say I’ll dirty my suit. I don’t care. Anyway, it’s  itchy. Now I’m lying flat on the floor under the chair. I have my gun so I have nothing to fear if the French attack. I’ll stay hidden.

I was scared again this morning when the poor came and rang the doorbell downstairs where the caretaker lives. Mama went down and I watched from the top of the stairs. They had beards, and holes in their clothes. They wanted money. They were selling shoelaces. Mama came back up and walked right past me, not even noticing me. She found a loaf of that bread I love, the white bread with a golden crust woven over the top of it like a girl’s braids, and she took it downstairs. When she handed it to the poor people they smiled at her and went back out into the street.

They came again this afternoon. She was still playing the piano, the piece that gets really fast at the end, she was laughing and I was spinning on the spot, watching the room swirl around me.

The beggars were back. I was first to hear them hammering at the door. Mama stopped playing and went down to open it. One of them was really yelling. He said their house had been taken, and their savings, and they’d been thrown onto the street with their children. He said it was because of the Jews. I was scared, I wanted to cry. Mama was kind to them and one of the men said he knew her, a tall, fat man with a big white beard.

“She’s a Feuchtwanger!” he boomed.

He got hold of the nasty little guy who was yelling and pulled him away. He explained that he’d been at school with Uncle  Lion  and  had  even  read  his  books. I hid upstairs, keeping watch with my rifle. I wished I was invisible, like in the book they read to me at bedtime. The man with the beard winked and told the little guy he was a pain with his nonsense about Jews. Mama thanked him sweetly and asked Rosie to fetch some sausages. Rosie’s my nanny. I rolled away like a soldier and she didn’t see me when she walked past. Her white apron and black dress made a rustling sound. I was under the chair. I watched her go to the kitchen. She muttered to herself in dialect, the different language she uses when no one’s listening. She said the poor were idiots; she cursed, saying we didn’t have all that many sausages, and she didn’t know what we’d have for dinner tonight. She came back with the sausages and gave the fat man a smile. He thanked her, blessed my mother and headed off with the gang.

Aunt Bobbie, our upstairs neighbor, came down and talked to Mama. I couldn’t really hear. I think Aunt Bobbie told her my uncle would make trouble for us if he wasn’t careful with his books. Uncle Lion’s a writer. He makes up stories for grown-ups. Mama smiled at Aunt Bobbie and promised to let Uncle Lion know. She tried to reassure her, telling her not to worry, saying the beggars were just poor people who’d been in the war and had lost everything. I ran to the window to watch them. They were ringing the bell at the building opposite, gathering together a little group with others from up the street.

I’ve been watching the poor through the window since this morning. They’re still there outside our building. What if they attacked? I have my rifle! When Mama spotted me earlier, she smiled, came over to me, drew the curtains and said it was time for tea. I asked her what a Jew was, and she whispered in my ear that I was too young to understand.

I may be five but I follow everything. I know what a Jew is! One time Papa talked to Mama about them in front of me. She as…