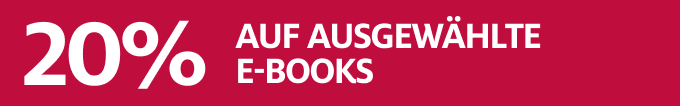

The Dead Can't Make a Living

Beschreibung

“A unique blend of tension, charm, tragedy, and optimism, with characters you’ll love and a setting so real you’ll think you’ve been there. Highly recommended.”--Lee Child, author of the Jack Reacher series Ed Lin''s big-hearted, ...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 31.60

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

“A unique blend of tension, charm, tragedy, and optimism, with characters you’ll love and a setting so real you’ll think you’ve been there. Highly recommended.”--Lee Child, author of the Jack Reacher series Ed Lin''s big-hearted, eye-opening fifth installment in the fan-favorite Taipei Night Market series Jing-nan, the owner of the most popular food stand in Taipei’s world-famous Shilin night market, is hauling trash after a successful evening of hawking;Taiwanese delicacies to tourists when he finds a corpse propped up against the dumpsters. The dead man turns out to be Juan Ramos, a Philippine national who came to Taiwan for a job at a massive ZHD food processing plant. Jing-nan is haunted by Ramos''s story, and by the heartbreak of his family, who arrive in Taipei looking for answers. ZHD has a history of safety violations, and activists have a hunch Ramos''s death might be part of a cover-up. Meanwhile, Jing-nan''s gangster uncle, Big Eye, has his own mysterious, probably illegal, reasons for being concerned about what''s going on in ZHD. He pressures Jing-nan into a daring and risky mission: going undercover as a migrant laborer to get a job at the food processing plant and report back about the conditions inside. Jing-nan hopes to find out the truth for the Ramos family, and to save other immigrant lives--but first he has to survive the spy operation.; <The Dead Can''t Make a Living <is at once a rollicking crime novel and a scorchingly timely examination of our global dependence on undocumented immigrants and the inhumane labor conditions that underpin modern conveniences.

Autorentext

Ed Lin is a journalist by training and an all-around stand-up kinda guy. He’s the author of four other novels in the Taipei Night Market series: Ghost Month, Incensed, 99 Ways to Die, and Death Doesn’t Forget as well as five other novels. Lin, who is of Chinese and Taiwanese descent, is the first author to win three Asian American Literary Awards. He lives in New York with his wife, actress Cindy Cheung, and son.

Leseprobe

Chapter 1

The teacher of my half-assed night-school class was Mr. Chiang, a man in his late 60s. A veteran of business management in offices stretching from Tokyo to Topeka, Mr. Chiang was so “professional” in appearance and demeanor, he didn’t seem Taiwanese.

Instead of the modestly parted hair that marked many Taiwanese men his age—should they still have an appreciable head of hair by that point—Mr. Chiang must’ve gone to a stylist and said, “Gimme waves that scream ‘southern California!’” He projected an aura of openness and ease, and smiled often. You’d think that at this time in the early evening he’d be wrapping up his day, or wrapping his arms around his secretary in his corner office on the top floor of the Taipei 101 building. But lasting success had eluded Mr. Chiang. Why else was he stuck teaching “Concepts of Business Management,” a preliminary class in a second-rate night school?

More important, why was I here?

Well, I had detoured from the road to success, too. I had been at UCLA, but dropped out when my father got cancer. Soon after I returned to Taiwan, I was an orphan saddled with family debt. I managed to rescue the family business, a night-market food stand, which now represented the totality of what my entire ancestral line had accomplished. Hey, some dynasties have done less.

But slinging skewers was only going to get me so far without a college degree, my girlfriend, Nancy, liked to remind me. As a concession to her and to reality, I’d enrolled in Mr. Chiang’s class, a prerequisite weeder run; students had to excel in order to place into classes that would lead to a degree.

How many of us would they let through? As confident as I was about my business acumen, I wasn’t so sure how my achievements so far stacked up against those of my classmates.

That first night in class, Mr. Chiang put us at ease by talking about himself, and the general state of business around the world today. In all honesty, I tuned out a little, until he said, “So tonight, each of you is going to stand in the front of the room and briefly tell us your life story.”

Briefly? Any words beyond our names seemed like too much! There were audible gasps, and one even came from me.

In Taiwanese society, people are loath to reveal anything personal in public or private, even when there’s nothing to be embarrassed about. Two generations of martial law has left a legacy of restraint in Taiwanese manners. Any detail about yourself—good, bad, or neutral—should be kept private. This behavior extends to money matters and permeates the deepest relationships. In fact, joint banking accounts don’t exist in Taiwan because even married couples keep their numbers away from each other. Only the most irresponsibly romantic spouses know each other’s PINs.

Upon hearing he’d have to speak about himself in front of the class, one young man grabbed his bag and flew out of the room like an evil spirit touched by a Taoist talisman. Mr. Chiang shook his head with amusement.

“There’s one guy who won’t be getting on the degree track,” he said to the class’s nervous chuckles. “Look,” he said in English, “You are the most important ingredient in business today. The persona that you present determines if you’re going to land that job or get that supply contract. Connecting on a personal basis is as important as the business plan. Maybe even more so.” Mr. Chiang swung his candy-red tie to the side and continued. “Say you’re a tea distributor. Would you rather do business with Chen blah blah who graduated from this or that college, or with someone who runs a farm that’s been in the same family for ten generations, through wars, national disasters, and generational divides?”

Mr. Chiang’s tie slithered back to center as he moved his arms animatedly.

“Let’s give more details. At one point that family was on the verge of selling out to the big, evil corporation, but then the prodigal daughter left her Wall Street job and returned to Taiwan to revive the farm.” In his left hand, Mr. Chiang cradled an imaginary canister of tea. “You’d have to be inhuman to not want to be in business with that family, and be a part of the story. In business, you’re always selling your story to customers, and to employees and business partners. You all understand the importance of your stakeholders, right?”

He looked from face to face and we nodded. Yes, we would have nodded at anything the teacher said, but his point really was sinking in.

Mr. Chiang smiled. “Good. Now, Mei-hua, come up and tell us about yourself.”

She seized up immediately, and the rest of us squirmed, knowing we’d eventually go up, as well.

“Class participation is a part of your grade,” Mr. Chiang added casually, knowing that the remark would cut to the heart of our fears. Mei-hua rose and shakily walked to the front of the class. “Don’t worry,” Mr. Chiang reassured her in his best reality TV host voice. “Everyone has to go eventually, and you get a lot of credit for being first.”

Mei-hua probably hadn’t planned on presenting herself to a room. She was wearing a thin gray sweatshirt and a black mid-length skirt. She wasn’t much taller than five feet, and looked shorter because she was hunched over. She tucked a lock of her shoulder-length black hair behind her right ear.

“I didn’t think there would be public speaking,” she said to her feet. “Isn’t this supposed to be a business class?&…