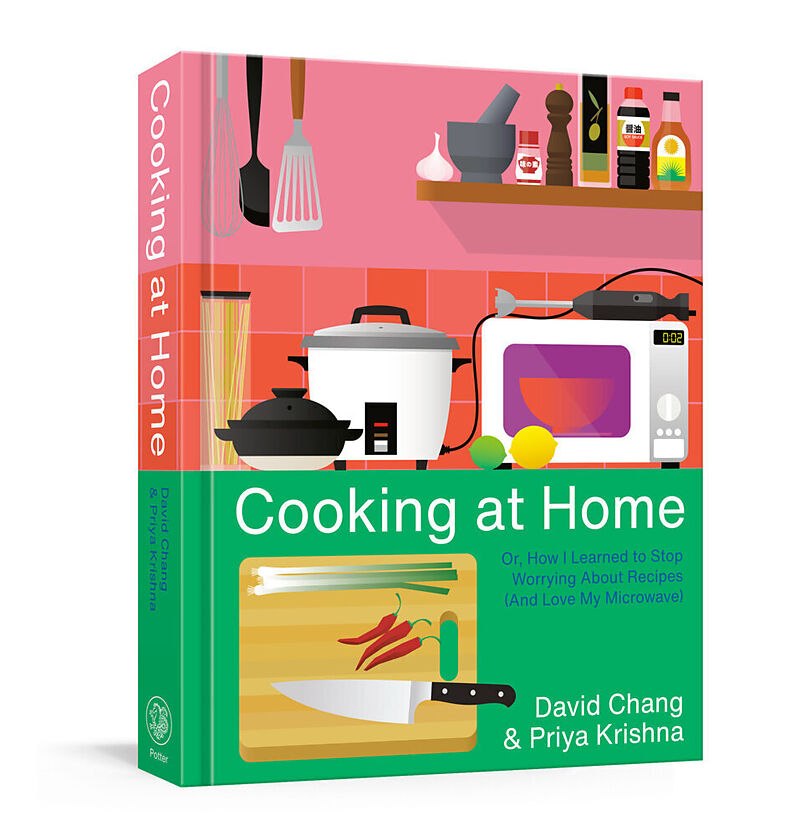

Cooking at Home

Beschreibung

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER The founder of Momofuku cooks at home . . . and that means mostly ignoring recipes, using tools like the microwave, and taking inspiration from his mom to get a great dinner done fast. JAMES BEARD AWARD NOMINEE ONE OF THE BEST COOKBOO...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 37.20

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER The founder of Momofuku cooks at home . . . and that means mostly ignoring recipes, using tools like the microwave, and taking inspiration from his mom to get a great dinner done fast.

JAMES BEARD AWARD NOMINEE ONE OF THE BEST COOKBOOKS OF THE YEAR: New York Post, Taste of Home

David Chang came up as a chef in kitchens where you had to do everything the hard way. But his mother, one of the best cooks he knows, never cooked like that. Nor did food writer Priya Krishna s mom. So Dave and Priya set out to think through the smartest, fastest, least meticulous, most delicious, absolutely imperfect ways to cook.

From figuring out the best ways to use frozen vegetables to learning when to ditch recipes and just taste and adjust your way to a terrific meal no matter what, this is Dave s guide to substituting, adapting, shortcutting, and sandbagging like parcooking chicken in a microwave before blasting it with flavor in a four-minute stir-fry or a ten-minute stew.

It s all about how to think like a chef . . . who s learned to stop thinking like a chef.

Autorentext

David Chang is the founder of Momofuku. His cookbook, Momofuku, and his memoir, Eat a Peach, are New York Times bestsellers. He lives in Los Angeles.

Priya Krishna is a food reporter for The New York Times and the author of the bestselling cookbook Indian-ish. She grew up in Dallas and currently lives in Brooklyn.

Klappentext

"The globally renowned chef of Momofuku, star of Netflix's Ugly Delicious, and bestselling author of Eat a Peach now shares the kitchen hacks and culinary tricks he uses as a new home cook for a growing family--and shows the rest of us how to make the most of our cooking skills ... Rather than outlining formal recipes, David talks through how he tackles a dish step by step, starting with a basic template and then turning to endless variations ... This cookbook is David's guide to unlocking culinary dark arts of shortcuts and hacks, brought to you by a chef who's made a career of doing everything the hard way ... and is as tired of doing it as you are of hearing about it"--

Zusammenfassung

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • The founder of Momofuku cooks at home . . . and that means mostly ignoring recipes, using tools like the microwave, and taking inspiration from his mom to get a great dinner done fast.

JAMES BEARD AWARD NOMINEE • ONE OF THE BEST COOKBOOKS OF THE YEAR: New York Post, Taste of Home

David Chang came up as a chef in kitchens where you had to do everything the hard way. But his mother, one of the best cooks he knows, never cooked like that. Nor did food writer Priya Krishna’s mom. So Dave and Priya set out to think through the smartest, fastest, least meticulous, most delicious, absolutely imperfect ways to cook.

From figuring out the best ways to use frozen vegetables to learning when to ditch recipes and just taste and adjust your way to a terrific meal no matter what, this is Dave’s guide to substituting, adapting, shortcutting, and sandbagging—like parcooking chicken in a microwave before blasting it with flavor in a four-minute stir-fry or a ten-minute stew.

It’s all about how to think like a chef . . . who’s learned to stop thinking like a chef.

Leseprobe

**Introduction

Dave Chang

*

I am a bad cook who can make delicious food. Yes, I’m a chef, but I’ve long felt that cooking doesn’t come naturally to me. It took me a while to realize, though, that what “cooking” meant had long been defined for* me, by others. First, by culinary school, where I was taught that there is a “right” way to cook and a “wrong” way to cook, whether it’s braising meats or saucing pasta. Then, early in my career, I worked primarily in European-fixated restaurants, where the whole point is to make the same thing, the same painstaking way, again and again. You have to follow the rules. You can’t just make stuff up. And so I forced myself to learn the rules.

Meanwhile, I never used to cook at home. In fact, I bragged in interviews about how my fridge was mostly just filled with beer. I lived in my restaurants. My apartment was a place to crash, so restaurant cooking was all the cooking I knew.

But that’s all changed now. I have a wife, a baby, and in-laws, and most of the time, it’s my job to feed them. I’ve had to learn to become a home cook for the first time in my life, and it’s entirely different from how I cook at restaurants. Now I make stuff up out of necessity, with my new guiding principles: to create something as delicious as possible, in the least amount of time possible, while making as little mess as possible.

At home, I am flying by the seat of my pants: I play fast and loose with my microwave, throw aesthetics out the window, and generally don’t adhere to any particular style or cuisine. When you’re busy and you have a family and you need to put food on the table, you do what you have to do. As I’m writing this, I am in the kitchen of a rental house, where my family has been quarantining because of the coronavirus pandemic. When we arrived, the cabinets had dried thyme and bouillon cubes—and that was it. I diluted a bouillon cube in water, mixed it with crushed tomatoes, and added some sugar, salt, and fish sauce that we brought with us. I served it over pasta. It was great.

And it was only after I started cooking at home that I realized that most of the rules you hear about cooking exist simply because someone made them up once. In our country, those rules are very often from a European perspective. They could be genius, rooted in science, or they could be totally arbitrary. But if all you’re taught is to just follow the rules, there’s no way to tell which is which. These ingredients only go with these ingredients. You don’t mix this with this. This recipe is a “project” while this recipe is “easy.” The fixation on rules means we’ve created generations of people who rely on recipes and can’t actually cook a dish without one.

But cooking is really simple if you do it the way I do now: a little sandbagging, a little food science, and a little intuition. Forget the “right” way to do things. Just learn to make it up as you go. Giving you the tools to do that, along with a whole bunch of dishes and ideas that work for me, is what this book is about.

Hi, it’s me—Priya. I’m switching to my perspective for a minute. This is how co-authorships work: I write as if I am Dave. In a lot of cases, I am literally just transcribing things Dave said to me. In others, I’m channeling my inner Dave Chang. But I wanted to interject as myself here, because maybe by the time you’ve gotten to this point you’ve realized you just purchased a cookbook

by a famous chef with no recipes and you’re confused. Or disappointed. Or panicked. Let me reassure you by saying that I felt all of that when I first sat down to write this book with Dave.

I kept it together for most of the meeting, but when I walked home, I was sweating. How the hell was I supposed to take the ramblings of this man who spoke mostly in philosophical ideas and sports metaphors and David Foster Wallace speeches and turn them into an actually useful cookbook?

The first few months, I just watched Dave cook. I took notes. I transcribed the rants. I tried to get him to abide by a rough recipe list we had put together, to no avail. I’d ask him how much fish sauce he put into the chicken stew and he would have already forgotten. I’d ask him to slow down on the flatbread so I could watch his technique and…