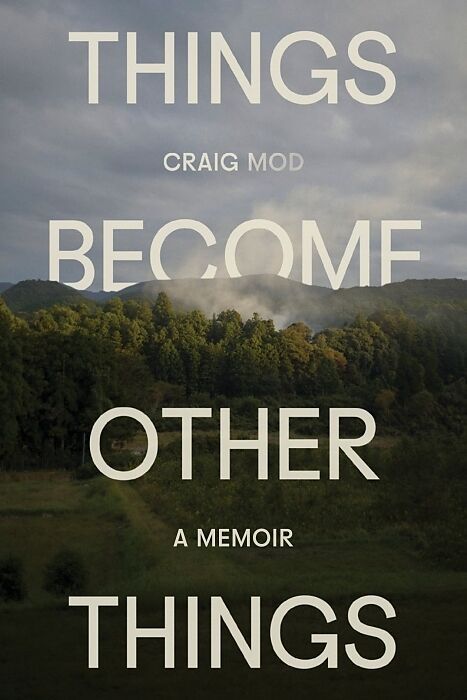

Things Become Other Things

Beschreibung

A transformative 300-mile walk along Japan’s ancient pilgrimage routes and through depopulating villages inspires a heart-rending remembrance of a long-lost friend, documented alongside remarkable photographs. Photographer and essayist Craig Mod is a vet...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 32.40

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

A transformative 300-mile walk along Japan’s ancient pilgrimage routes and through depopulating villages inspires a heart-rending remembrance of a long-lost friend, documented alongside remarkable photographs. Photographer and essayist Craig Mod is a veteran of long solo walks. But in 2021, during the pandemic shutdown of Japan’s borders, one particular walk around the Kumano Kodō routes--the ancient pilgrimage paths of Japan’s southern Kii Peninsula--took on an unexpectedly personal new significance. While passing the peninsula’s shrinking villages, Mod found himself reflecting on his own childhood in a post-industrial American town, his experiences as an adoptee, his unlikely relocation to Japan as a student at age nineteen, and his relationship with one lost friend, whose life was tragically cut short after their paths diverged. As the days passed, he considered why he has walked so rigorously and religiously during his twenty-five years as an immigrant in Japan, contemplating the power of walking itself. For Mod, solo walks are a tool to change the very structure of his mind, to better himself, and to bear witness to a quiet grace visible only when “you’re bored out of your skull and the miles left are long.” Through the frame of a 300-mile-long pilgrimage walk, <Things Become Other Things< blends memoir and travel writing at their best, transporting readers to an otherwise inaccessible Japan, one only made visible through Mod’s unique bicultural lens....

Autorentext

Craig Mod

Leseprobe

B.—allow me to begin again, just for you.

Why am I drawn back to this place? To this peninsula, the Kii Peninsula? This once-wiped-clean land of lost villages and dusty roads, of fallen-pilgrim graves and boats stuck in the earth? In part, it’s because they say the stone here suffers few dickheads, is happy to chuck you off given the slightest vanity. Us—two dickheads without vanity, from a place that never knew vanity: buzzed skulls, stained T-shirts and jeans, sneakers with half-attached soles. Walking these roads and ridges you’d have made it for sure, I know this now. Touching this rock, walking these paths, I’ve found an unexpected peace in these recondite hinterlands.

I admire the old road and rock, but the people—their stories, their immutable connection to this place—have brought me back again and again. Their language enchants: a delightfully foul mellifluousness, a soiled twang we know well. And it’s these people and their words that make me think of you more than anything else.

It’s been a lifetime since I’ve written your name: Bryan. (There it is.) Written with a “y” not an “i.” The only “true” way to write it as far as I’m concerned. A name that never left my mind. (How could it?) Bryan. But it wasn’t until this walk that you returned to me in full. Why now? I don’t know. Maybe I’d just seen enough, finally. Was finally brave enough to look back.

Here’s what I do know: This world turns and turns and the more I move my feet the more I believe in things we never understood. Life, irrepressible, it billows over the top of the pot, man. Let me be your eyes as best as I can. I’ll bear witness to this wonder you never got to see.

Howdy

Twenty-seven years since we last spoke, a catch-up is in order. Here are the broad facts: I’m now forty-one. I moved to Japan when I was nineteen. I walk a lot, mostly alone, always compulsively, down these old Japanese roads.

I walk twenty, thirty, sometimes forty or more kilometers until my feet feel wonky, hot in spots, minced. Until I’m sure I can’t take another step. And then do the same thing again the next day. And then the next. Repeat this for weeks, months. I do this easily, as if my body has been waiting for this my whole life. I photograph those I meet, the things I see, the banalities of life I pass. I dictate my observations and thoughts into a recorder, talking to myself like that bag lady who roamed our suburban sidewalks, who walked past our homes. (Why didn’t any of us try to help her?) Each night, I spend three or four or five hours collating the photographs, compiling my notes, doing laundry, chatting with inn owners, creating an archive. Where does it all go? Here, you’re holding it. The whole thing, an ascetic practice. I even shave my head like some performative mendicant, one who lives off stories as alms. This is a walk, yes, but also a series of relationships with people and objects: purpose wrought from a slideshow of faces, old tales, new tales, histories, fields, forest climbs, pachinko parlors, and pine trees.

...

Down the road I see what might be a kissa, an old café. These have become my favorite places of all the places in the world—kissaten or kissa for short, Japanese cafés with the air of mid-century American diners but entirely of their own mirror-world aesthetic. Low Formica tables, low seats. “Sofa seats,” they’re called. (I love that—sofa seats.) Kissas are smoky, creaky community hubs. Sit in the right one for an hour and, if nothing else, you’ll understand the town a bit better. The oncoming shop’s canvas awnings look like they’ve been shredded by storms. The place looks abandoned, let me tell you. Like it had been murdered and thrown in a ditch, pulled out, assessed, deemed worthless, dumped back in. But the day is hot and I’m thirsty and the sign says “Howdy.”

Inside, the owner is head-down in a newspaper, smoldering cigarette aloft in hand. She doesn’t look up.

Ain’t got no toast, she says. (They often serve toast.)

You got iced coffee?

Yeah, we got iced coffee. (They always serve iced coffee.)

The place is empty. I use the toilet, which is in great shape—old-style ceramic hole in a porcelain-tiled floor. A toilet from a different era, one that requires good balance, haunches like a sumo wrestler’s. I once saw a toilet made specifically for the emperor. It was in a small village along another historic route called the Kiso-ji, far from this kissa.

Hundreds of years ago, rumor had it, the emperor was going to pass through. God forbid he need to shit. So they made a beautiful toilet—wooden. (Yes, a wooden toilet.) A hole in the floor, perfectly oblong, lined with aromatic cypress, filled with sand, with a nice little handle poking up at one end to aid with balance. Hitch up your kimono, hold on, that sort of thing. The ceiling was of a delicate woven thatch. Truly, a slyly cultivated place to empty your guts. Why a pit of sand, as if the emperor were a cat? Because his stool needed to be checked. There was an official sifter. A man who analyzed all imperial bowel movements to make sure the godhead was OK. What a job. These things exist, believe it or not. The stories we tell ourselves, the way we elevate this human over another human—so arbitrary, so bizarre. That toilet in the middle of nowhere never did get used. But the town enshrined it in a way, keeps it on display. You can go visit if you’re nearby.

Here in Howdy, the toilet is more or less the same, but with plumbing—not sand—and has clearly been used a few thousand times. Next to it sits a dented-up aluminum ashtray. The place once filled with tobacco smoke, still suffused with the exhaust of a thousand smokers. Over the last decade, laws changed as the Olympics approached. (The Olympics changed Tokyo in 1964 and once again in 2020.) When I first arrived in 2000, everyone seemed to smoke everywhere. You’d have to shower three times to get the smoke out of your hair. But now it’s more strict. Hardly anywhere allows smoking anymore. These old kissas are the l…