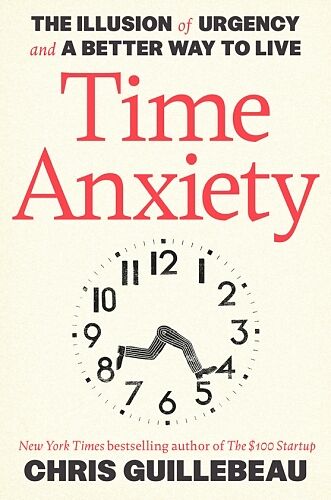

Time Anxiety

Beschreibung

Autorentext Chris Guillebeau is the New York Times bestselling author of The $100 Startup, Side Hustle, and The Happiness of Pursuit, among other books, which have sold over one million copies worldwide. During a lifetime of self-employment that included a fou...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 22.70

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

Autorentext

Chris Guillebeau is the New York Times bestselling author of The $100 Startup, Side Hustle, and The Happiness of Pursuit, among other books, which have sold over one million copies worldwide. During a lifetime of self-employment that included a four-year commitment as a volunteer executive in West Africa, he visited every country in the world (193 in total) before his thirty-fifth birthday.

Leseprobe

1

Start by Giving Yourself More Time

Before you can make big decisions about your life, you need to reduce the immediate pressure you feel.

When I started writing this book, I first outlined lots of ideas about mortality, leaving a legacy, and how to complete big projects.

We’ll come back to some of that later. But as my editor and I poured over the survey results, we realized that time anxiety prevents people from moving forward in some very basic operations of life.

Over and over, readers said things like:

“I get absolutely frozen and can’t make simple decisions.”

“I’ve had the same important task at the top of my to-do list for ten days in a row, but I just can’t bring myself to face it.”

“It feels like everyone else understands something very simple that I don’t get at all.”

They also tended to use absolute terms such as “always,” “never,” and “constantly” to describe their struggles with time. They’ve always felt this way, they would never be better, and they constantly felt the pull of wondering if they were spending their time well.

Anxiety inhibits your ability to think clearly in the moment. When you feel anxious, you don’t always make rational decisions. Sometimes you know what you should do, but you feel incapable of doing it. Other times, you don’t have any idea what you should do—you just know what you’re doing now isn’t good.

Either way, you feel trapped. And when you’re trapped, the first step is to locate an escape route.

You would not tell a person experiencing a panic attack that they need to get to work on filing their taxes, break up with their boyfriend, and mail off an overdue rent check. Perhaps they need to do all of those things eventually, but they first need to deal with what feels like an emergency. (And simply telling them to “calm down” probably won’t help much.)

They need to learn to address their breathing, lower their heart rate, and understand that even though what they are feeling seems overwhelming, it will get better. Only once they’re able to do these things will they be able to deal with more systemic problems.

Those actions I mentioned—lowering your heart rate, noticing your breath patterns—are part of regulating your nervous system, the essential part of your body that allows you to do any sort of cognitively intensive work. When this delicate ecosystem is in balance, you’re at your best. You’re able to make decisions, plan ahead, and manage your emotions with relative ease. Throw in stress or anxiety, however, and suddenly the ecosystem is under threat.

When you’re struggling with time anxiety, you need to deal with the immediate symptoms first. One of the reasons why you experience distress is because you perceive a time shortage in your life. Therefore, let’s help you achieve a time surplus, where more time is available to you, even in the midst of a busy life.

I’ll show you some strategies for this in the chapters that follow, including:

When to do things poorly (Not everything needs to be done with excellence or even done well.)

Why not finishing things is perfectly acceptable (Many things can be left undone, often permanently.)

How to decide “What is enough?” for any type of project or creative work, so that you always have an end point in mind

But for now, try taking some quick actions that can help you right away. These actions will give you space to make bigger decisions and figure out how you really want to spend your time.

- Practice “Time Decluttering”

Home-organizing guides often focus on decluttering, the act of removing items from your home or work space that don’t have a useful or joyful purpose. It can be a useful habit at times.

But while physical decluttering and improving your environment can help some-what, time anxiety usually stems from worries in our mind or commitments that occupy our schedule. It’s a little different from, “I’ve got too many socks, so I should pare down.”

That’s why, in addition to any physical tidying up that you do, look at your calendar for the next few weeks and challenge yourself to remove a few items. Most likely, you can find some upcoming appointments that seemed like a good idea when you added them but now feel less important.

Later I’ll show you a concept called rules of engagement that will help you make fewer commitments in the first place, but you can practice time decluttering without any further knowledge.

Go through your schedule and ask, “Do I need to do this thing? Is it serving a purpose in my life? Do I still want to do it?”

See what you can remove, and notice how it feels to reclaim that time as a gift to yourself. It’s an easy but powerful way to multiply the time that’s available to you in the near future.

ACTION: Can you clear at least two items from your calendar for the next week?

- Put a Brick in Your Inbox

How accessible are you right now? How many people have a direct line to your attention span?

Most of us have multiple “inboxes” where people can reach us. I don’t just mean any email inboxes you have, although those certainly count. But in addition, we have voicemail and voice memos, social media profiles that allow for direct messaging, apps with communication features, and more. Then of course, there are work networks (Teams, Slack, WhatsApp, others) that many employees are expected to participate in. For you, there might be something else I haven’t mentioned.

Guess what? Being accessible all the time is costly! You can get some of your attention back by stepping away from some of these tools or at least minimizing your use of them.

ACTION: Think through all the different ways that people can get your attention. Can you turn off at least one of these inboxes?

I know this feels difficult to some people, including some who believe they simply can’t lower the level of access they provide to the world. If that’s you, understand that you are not powerless. There’s something you can do, even if it seems small.

Note: I’m not suggesting that you lessen your availability for anyone who’s physically dependent on you, such as young children. In fact, turning off some of your accessibility elsewhere will allow you to be more present for the people you care most about.

One way or another, start resisting the expectation that your attention span is up for grabs. It shouldn’t be—it belongs to you, after all.

Notice How It Feels to Give Yourself Time

Taken together, actions like these point to an overall strategy of giving yourself more time. Do whatever you can to achieve this result. You could extend the idea even further by:

Removing annoying, time-wasting apps from your phone

Turning off all but the most essential notifications

No longer agreeing to requests and commitments without thinking about them*

*Instead, pause and consider: Is this really something I want to do? If I agree to the request, what will I be passing up on?

As you do this, notice how it feels. Isn’t it nice? You’ve b…