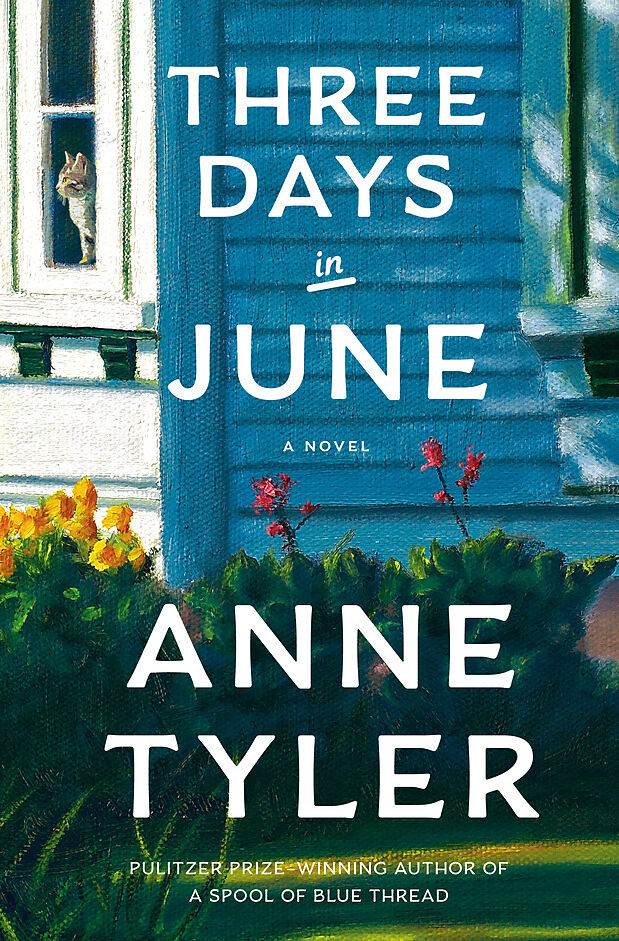

Three Days in June

Beschreibung

A new Anne Tyler novel destined to be an instant classic: a socially awkward mother of the bride navigates the days before and after her daughter''s wedding. Gail Baines is having a bad day. To start, she loses her job--or quits, depending on whom you ask. Tom...Format auswählen

- Kartonierter EinbandCHF 20.30

- Fester EinbandCHF 31.10

- BroschiertCHF 33.20

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

A new Anne Tyler novel destined to be an instant classic: a socially awkward mother of the bride navigates the days before and after her daughter''s wedding. Gail Baines is having a bad day. To start, she loses her job--or quits, depending on whom you ask. Tomorrow her daughter Debbie is getting married, and she hasn’t even been invited to the spa day organized by the mother of the groom. Then, Gail’s ex-husband Max arrives unannounced on her doorstep, carrying a cat, without a place to stay and without even a suit. But the true crisis lands when Debbie shares with her parents a secret she has just learned about her husband-to-be. It will not only throw the wedding into question but also stir up Gail and Max’s past. Told with deep sensitivity and a tart sense of humor, full of the joys and heartbreaks of love and marriage and family life, <Three Days in June< is a triumph, and gives us the perennially bestselling, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer at the height of her powers.

Autorentext

ANNE TYLER was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1941 and grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina. She is the author of more than twenty novels. Her twentieth novel, A Spool of Blue Thread, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2015. Her eleventh novel, Breathing Lessons, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1989. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She lives in Baltimore, Maryland.

Leseprobe

one

Day of Beauty

People don’t tap their watches anymore; have you noticed?

Standard wristwatches, I’m talking about. Remember how people used to tap them?

My father, for instance. His watch was a Timex with a face as big as a fifty-cent piece, and whenever my mother kept him waiting he would frown down at it and give it a tap. Implying, I suppose now, “Can this possibly be correct? Could it really be this late?” But when I was a little girl, I imagined he was trying to make time move faster—to bring my mother before us instantly, already wearing her coat, like someone in a speeded-up movie.

What reminded me of this recently was that Marilee Burton, the headmistress at the school where I worked, called me into her office one Friday morning as I was walking past. “Come chat for a moment, why don’t you?” she said. This was not a regular occurrence. (We were on more or less formal terms.) She waved toward the Windsor chair facing her desk, but I stayed in the doorway and cocked my head at her.

“I thought I should let you know,” she said, “I won’t be coming in on Monday. I have to have a cardioversion.”

“A what?” I asked.

“A procedure for my heart. It’s been beating wrong.”

“Oh,” I said. I couldn’t pretend to be surprised. She was one of those ladylike women who wear heels on all occasions, the perfect candidate for heart issues. “Well, I’m sorry to hear that,” I told her.

“They’re giving it an electrical jolt that will stop it and then start it again.”

“Huh,” I said. “Like tapping a watch.”

“Pardon?”

“Is it dangerous?” I asked.

“No, no,” she said. “I’ve had it done once before, in fact. But that was over spring break, so I didn’t see the need to announce it.”

“Okay,” I said. “And how long will you be out of the office?”

“I’ll be back on Tuesday, good as new. No need to alter your routine in the slightest. However,” she said, and then she sat straighter behind her desk; she cleared her throat; she briskly aligned a stack of papers that didn’t need aligning. “However, it brings me to a subject I’ve been meaning to discuss with you.”

I stood a bit straighter myself. I am very alert to people’s tones of voice.

“I’ll be sixty-six years old on my next birthday,” she said, “and Ralph just turned sixty-eight. He’s starting to talk about traveling a bit, and seeing more of the grandchildren.”

“Really.”

“So I’m thinking of handing in my resignation before the new school year begins.”

The new school year would begin in September. We were already in late June.

I said, “So . . . does this mean I’ll take over as headmistress?”

It was a perfectly logical question, right? Somebody had to do it. And I was next in line, for sure. I’d been Marilee’s assistant for the past eleven years. But Marilee let a small silence develop, as if I’d presumed in some way. Then she said, “Well, that’s what I wanted to chat about.”

She selected the top sheet on her stack of papers, and she turned it around to face me and slid it across her desk. I stepped forward, grudgingly. I squinted at it. A typewritten page with a newspaper clipping stapled to one corner—a black-and-white photo of a serious young woman with energetically curly dark hair. “Nashville Educator’s Study on Learning Differences Wins McLellan Prize,” the headline read.

I said, “Nashville?” (We lived in Baltimore.) And I had no idea what the McLellan Prize was.

“I brought her name to the board’s attention when I first began to think of retiring,” Marilee said. “Dorothy Edge; maybe you’ve heard of her. I’d read her book, you see, and I’d found it very impressive.”

“You brought her to the board’s attention,” I repeated.

“After all, Gail,” she said. “You’re sixty-one years old, am I right? You won’t be working much longer yourself.”

“I’m sixty-one years old!” I said. “Nowhere near retirement age!”

“It’s not only a matter of age,” she told me. She was looking at me with her chin raised, the way people do when they know they’re in the wrong. “Face it: this job is a matter of people skills. You know that! And surely you’ll be the first to admit that social interactions have never been your strong point.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked her. “What possible interactions could you be referring to?”

“I mean, of course you have many other skills,” Marilee said. “You’re much more organized than I am. You’re a much better public speaker. But look at just now, for instance. I tell you I have a heart condition and you just say, ‘Oh,’ and pass right on to the question of taking over my job.”

“I said, ‘Oh,’ ” I reminded her. “I said, ‘I’m sorry to hear that.’ ” (Another of my strengths is that I have a very good audial memory, including for my own words.) “What more did you require of me?”

“I ‘required’ nothing at all,” she said, and now her chin was practically pointed at the ceiling. “All I’m saying is, to head a private girls’ school you need tact. You need diplomacy. You need to avoid saying things like ‘Good God, Mrs. Morris, surely you realize your daughter doesn’t have the slightest chance of getting into Princeton.’ ”

“Katy Morris couldn’t get into a decent trade school,” I said.

“That’s not the point,” Marilee said.

“So?” I said. “Just because I refuse to sweet-talk all your rich-guy parents I’m doomed to stay on forever as assistant headmistress?”

“Or,” Marilee said, and now she lowered her chin and gazed at me directly across the expanse …