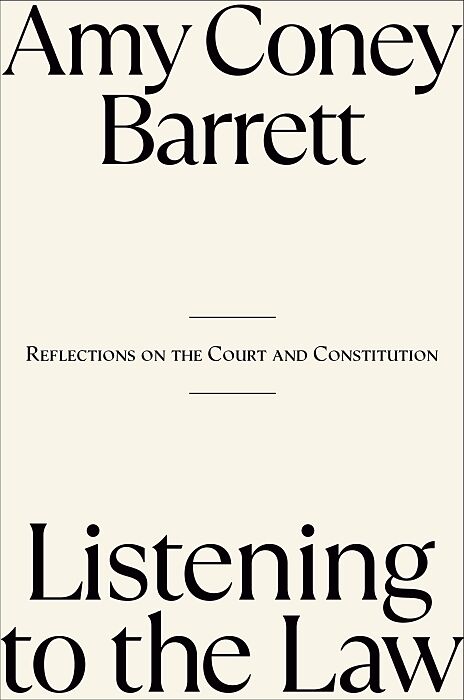

Listening to the Law

Beschreibung

From Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a glimpse of her journey to the Court and an account of her approach to the Constitution Since her confirmation hearing, Americans have peppered Justice Amy Coney Barrett with questions. How has she adjusted to the...Format auswählen

- Fester EinbandCHF 33.50

Wird oft zusammen gekauft

Andere Kunden kauften auch

Beschreibung

From Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a glimpse of her journey to the Court and an account of her approach to the Constitution

Since her confirmation hearing, Americans have peppered Justice Amy Coney Barrett with questions. How has she adjusted to the Court? What is it like to be a Supreme Court justice with school-age children? Do the justices get along? What does her normal day look like? How does the Court get its cases? How does it decide them? How does <she< decide?

In <Listening to the Law<, Justice Barrett answers these questions and more. She lays out her role (and daily life) as a justice, touching on everything from her deliberation process to dealing with media scrutiny. With the warmth and clarity that made her a popular law professor, she brings to life the making of the Constitution and explains her approach to interpreting its text. Whether sharing stories of clerking for Justice Scalia or walking readers through prominent cases, she invites readers to wrestle with originalism and to embrace the rich heritage of our Constitution.

Autorentext

Amy Coney Barrett

Leseprobe

Chapter 1

My Life in the Law

On my desk at home, I keep a picture of my great-grandmother's small house. I didn't know my great-grandmother; she died five years before I was born. Nor did I ever visit the house while family lived in it. I saw it for the first time almost ten years ago, when my siblings and I rented a party bus to take my parents on a "This Is Your Life" tour of New Orleans for my father's seventieth birthday. As lifelong New Orleanians, my parents have a long list of places with special memories, including this house on Green Street, where my mother spent many Sunday afternoons. On a lark, we knocked on the door to see if the owners would let us peek inside. They did.

The thing that struck me most was its size: tiny. The house was a single-story with a small living room, compact kitchen, and three bedrooms. The space seemed suitable for a small family. My great-grandmother, however, was a widow with thirteen children. (In a moment that must have been heart-wrenching, she discovered her pregnancy with the thirteenth after her husband's funeral.) She purchased the house with the proceeds of her husband's life insurance policy, knowing that no one would rent to a woman living alone with such a large family. The children didn't all move in with her: one had tragically died, and the oldest few were living independently. Still, the house was bursting at the seams. While I was surveying the tight space, my mother told me that my great-grandmother had also taken in three relatives who needed lodging. It was the Great Depression, so everyone was struggling. And as if she didn't have enough mouths to feed, she welcomed the many homeless men traveling through the neighborhood with food on the back porch. (She allowed them to sleep under her raised house until one fell asleep with a cigarette in his mouth and started a fire. After that, it was dinner only.) Little wonder that my great-grandmother has legendary status in our family.

Though my great-grandmother's generosity is inspiring, it's not why I keep the picture. Standing inside her small house, I couldn't believe how much she had fit into her life. At the time we made this visit, I was feeling more than a little sorry for myself. My husband, Jesse, and I were balancing two careers (I as a law professor, he as a federal prosecutor) and seven young children. On the one hand, we had every reason to be happy-we loved each other, our children, and (most of the time) our jobs. On the other hand, life had also thrown us some curveballs-like our youngest son's diagnosis of Down syndrome, which added new medical appointments and educational challenges to our already full schedule. I was feeling overwhelmed and wondering whether we could pull it all off. This window into my great-grandmother's life strengthened my resolve. Somehow, she always managed to find the resources, space, and time. With much less than I have, she took on much more. Looking at the photo reminds me of a woman who stretched herself beyond all reasonable capacity. I'm not sure that I'll be able to manage my life with the same grace that she had. But she motivates me to keep trying.

I didn’t grow up wanting to be a lawyer. Since I loved to read, I dreamed mostly about being an author or an English teacher. That was true through college, where I majored in English and spent most of my time reading literature and writing essays about it. Inspired by my college mentors, I considered pursuing a PhD in English, followed by a career as an English professor. But when it came time to apply, I hesitated. I loved literature but felt pulled by law. It too relied on words, but to a very different end. Law governs the relationship of the government to its citizens and its citizens to one another. It matters in everything from the sale of property to a criminal trial to the structure of government. No matter the context, law has real-world consequences. I wanted to know how it worked and to help people navigate it. (I also thought it might be easier to get a job as a lawyer than as an English professor.) In 1994, I walked into my first class at Notre Dame Law School.

I loved studying the law. Granted, reading cases was not as captivating as reading Shakespeare-but they held my attention all the same. I liked pulling out their logic to see whether it held up. Both in and out of class, I enjoyed debating issues like how the Constitution should be interpreted and whether it was just. And though I had the same nerves as every other first-year law student staring down final exams, I did well, which increased my confidence. While home on a holiday break, I ran into a high school teacher who asked how law school was going; I recall gushing that I had found the perfect fit. Saying it out loud drove home how true it was. From the first day of class, I never doubted my choice to become a lawyer.

I was unsure what kind of law I wanted to practice, but I knew where I wanted to do it: New Orleans, where I grew up and where my tight-knit extended family still lived. I thought I'd start at a law firm and perhaps shift later to teaching or public interest work. I was not, however, focused single-mindedly on my career-I wanted the path I chose to be compatible with raising the children I hoped to have. I loved growing up in a large family and wanted to have one myself. When I considered my future, I thought mostly about how to pull off being a working mother with a full house. Becoming a judge was not my ambition.

I left Notre Dame in May 1997 with a diploma and friendships I still treasure. And taking what I saw as a detour on my way to New Orleans, I headed to Washington to spend two years as a law clerk, a job that functions as a highly prized apprenticeship for a recent law school graduate. (I'll tell you more about the work of law clerks later in the book.) I worked first for Judge Laurence H. Silberman on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and then for Justice Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court of the United States. Both clerkships influenced me greatly-in fact, they changed the course of my career.

I had never met anyone like Judge Silberman. In addition to stints in private practice, he had served as the ambassador to Yugoslavia, deputy attorney general, solicitor of labor, and undersecretary of labor. His interests were as varied as his experience. We clerks (there were three of us) had to be ready to field questions not only on our cases, but also on foreign affairs, domestic politics, twentieth-century world history, and even his hobby of boating. We went to lunch several times a week, often at the Department of Labor cafeteria (which the judge loved for nostalgia's sake), where he regaled us with stories about his service in the Nix…